SEO

Introduction

Search Engine Optimization (SEO) isn’t just a hobby or a side project for digital marketers, it is crucial for the success of a website. The primary goal of SEO is to make sure that a website is optimized for the search engine bots that need to crawl and index its pages, as well as for the users that will be navigating the website and consuming its content. SEO impacts everyone working on a website, from the developer who is building it, through to the digital marketer who will need to promote it to new potential customers.

Let’s put the importance of SEO into perspective. Earlier this year, the SEO industry looked on in horror (and fascination) as ASOS reported an 87% decrease in profits after a “difficult year”. The brand attributed their issues to a drop in search engine rankings which occurred after they launched over 200 microsites and significant changes to their website’s navigation, among other technical changes. Yikes.

The purpose of the SEO chapter of the Web Almanac is to analyze on-site elements of the web that impact the crawling and indexing of content for search engines, and ultimately, website performance. In this chapter, we’ll take a look at how well-equipped the top websites are to provide a great experience for users and search engines, and which ones still have work to do.

Our analysis includes data from Lighthouse, the Chrome UX Report, and HTML element analysis. We focused on SEO fundamentals like <title> elements, the different types of on-page links, content, and loading speed, but also the more technical aspects of SEO, including indexability, structured data, internationalization, and AMP across over 5 million websites.

Our custom metrics provide insights that, up until now, have not been exposed before. We are now able to make claims about the adoption and implementation of elements such as the hreflang tag, rich results eligibility, heading tag usage, and even anchor-based navigation for single page apps.

Read on to find out more about the current state of the web and its search engine friendliness.

Fundamentals

Search engines have a three-step process: crawling, indexing, and ranking. To be search engine-friendly, a page needs to be discoverable, understandable, and contain quality content that would provide value to a user who is browsing the search engine results pages (SERPs).

We wanted to analyze how much of the web is meeting the basic standards of SEO best practices, so we assessed on-page elements such as body content, meta tags, and internal linking. Let’s take a look at the results.

Content

To be able to understand what a page is about and decide for which search queries it provides the most relevant answers, a search engine must be able to discover and access its content. What content are search engines currently finding, however? To help answer this, we created two custom metrics: word count and headings.

Word count

We assessed the content on the pages by looking for groups of at least 3 words and counting how many were found in total. We found 2.73% of desktop pages that didn’t have any word groups, meaning that they have no body content to help search engines understand what the website is about.

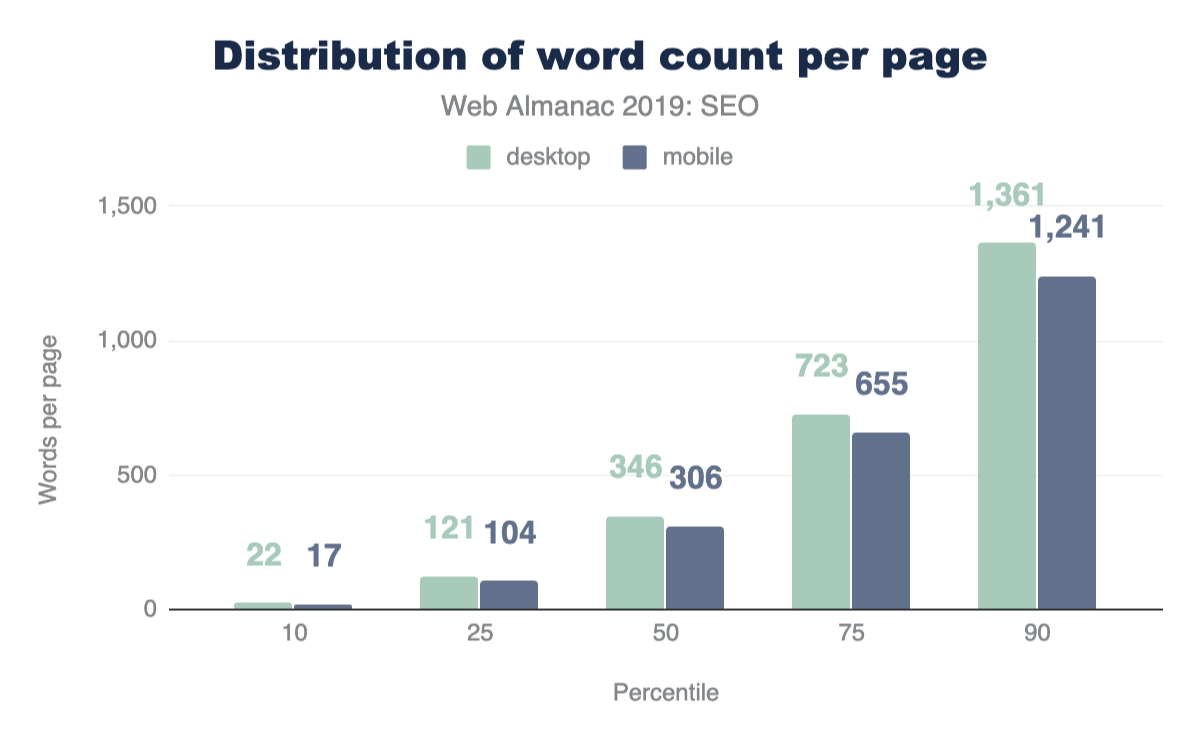

The median desktop home page has 346 words, and the median mobile home page has a slightly lower word count at 306 words. This shows that mobile sites do serve a bit less content to their users, but at over 300 words, this is still a reasonable amount to read. This is especially true for home pages which will naturally contain less content than article pages, for example. Overall the distribution of words is broad, with between 22 words at the 10th percentile and up to 1,361 at the 90th percentile.

Headings

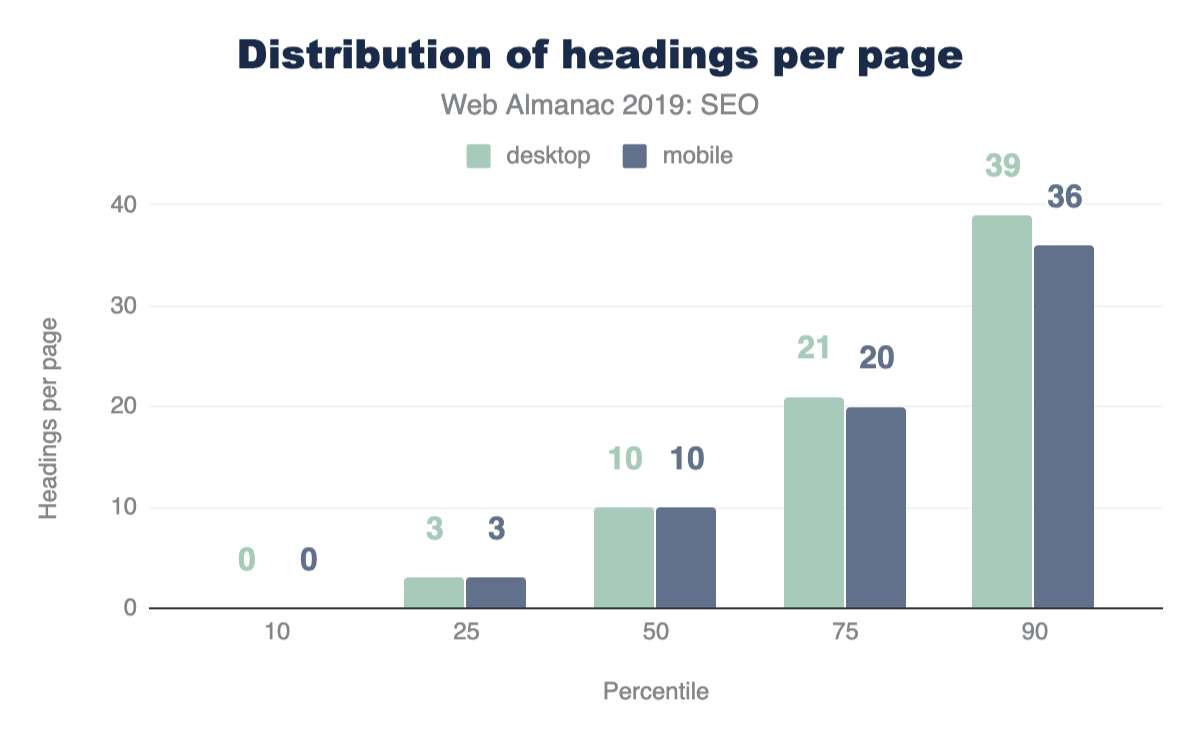

We also looked at whether pages are structured in a way that provides the right context for the content they contain. Headings (H1, H2, H3, etc.) are used to format and structure a page and make content easier to read and parse. Despite the importance of headings, 10.67% of pages have no heading tags at all.

The median number of heading elements per page is 10. Headings contain 30 words on mobile pages and 32 words on desktop pages. This implies that the websites that utilize headings put significant effort in making sure that their pages are readable, descriptive, and clearly outline the page structure and context to search engine bots.

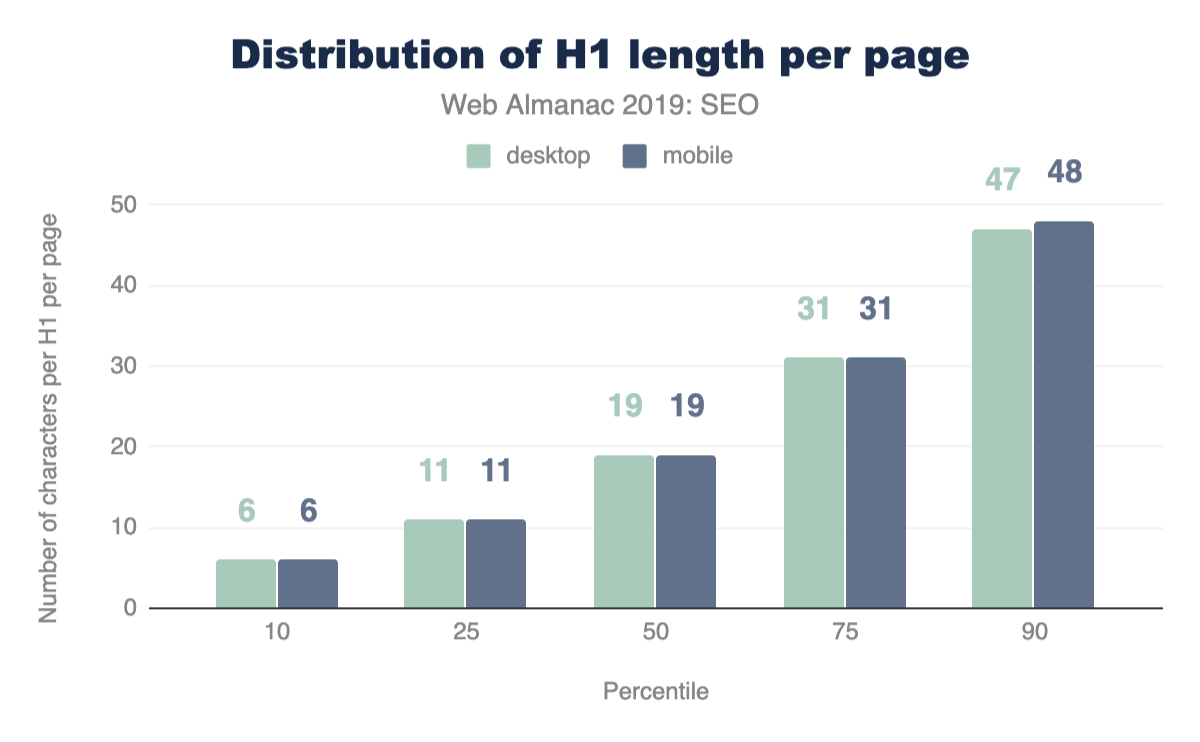

In terms of specific heading length, the median length of the first H1 element found on desktop is 19 characters.

For advice on how to handle H1s and headings for SEO and accessibility, take a look at this video response by John Mueller in the Ask Google Webmasters series.

Meta tags

Meta tags allow us to give specific instructions and information to search engine bots about the different elements and content on a page. Certain meta tags can convey things like the topical focus of a page, as well as how the page should be crawled and indexed. We wanted to assess whether or not websites were making the most of these opportunities that meta tags provide.

Page titles

<title> tag.

Page titles are an important way of communicating the purpose of a page to a user or search engine. <title> tags are also used as headings in the SERPS and as the title for the browser tab when visiting a page, so it’s no surprise to see that 97.1% of mobile pages have a document title.

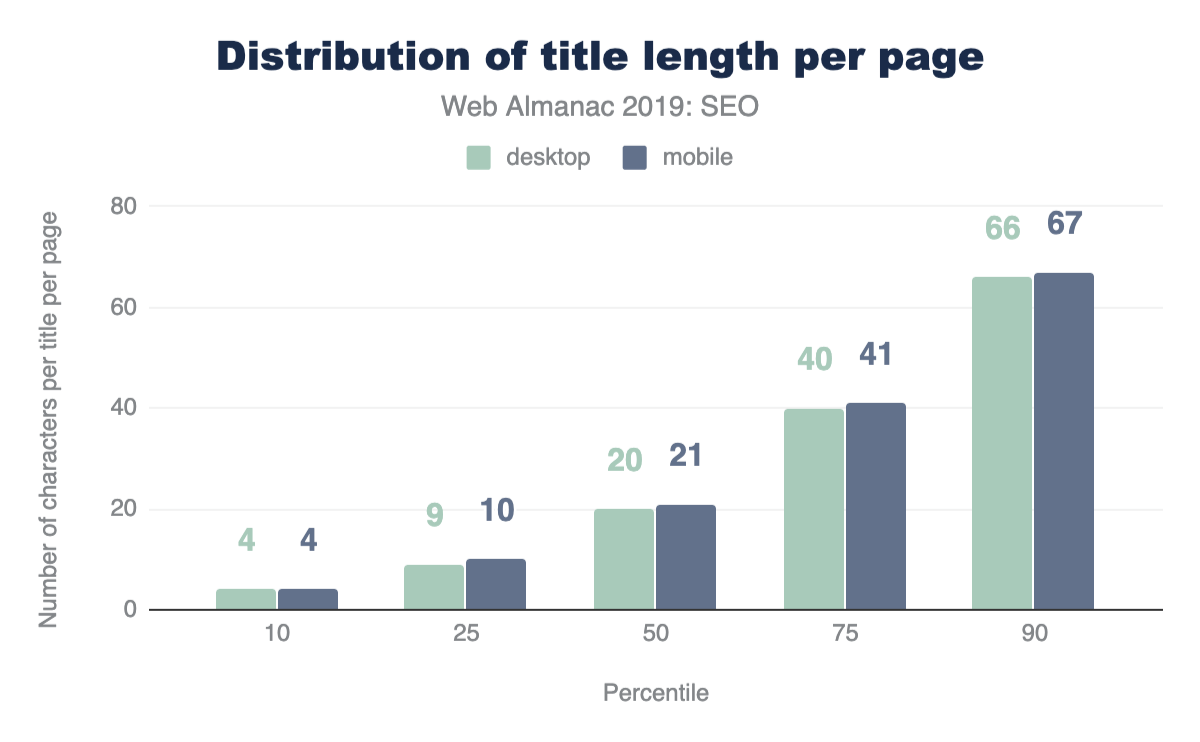

Even though Google usually displays the first 50-60 characters of a page title within a SERP, the median length of the <title> tag was only 21 characters for mobile pages and 20 characters for desktop pages. Even the 75th percentile is still below the cutoff length. This suggests that some SEOs and content writers aren’t making the most of the space allocated to them by search engines for describing their home pages in the SERPs.

Meta descriptions

Compared to the <title> tag, fewer pages were detected to have a meta description, as only 64.02% of mobile home pages have a meta description. Considering that Google often rewrites meta descriptions in the SERPs in response to the searcher’s query, perhaps website owners place less importance on including a meta description at all.

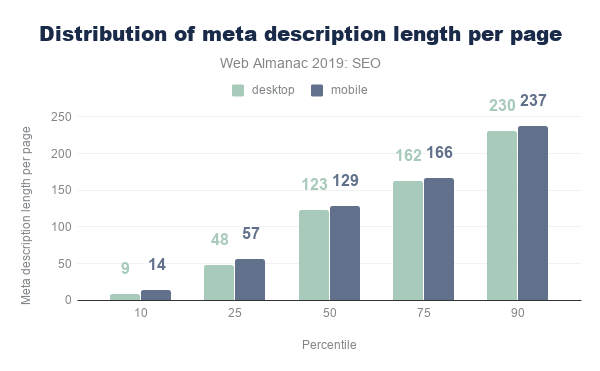

The median meta description length was also lower than the recommended length of 155-160 characters, with desktop pages having descriptions of 123 characters. Interestingly, meta descriptions were consistently longer on mobile than on desktop, despite mobile SERPs traditionally having a shorter pixel limit. This limit has only been extended recently, so perhaps more website owners have been testing the impact of having longer, more descriptive meta descriptions for mobile results.

Image alt tags

Considering the importance of alt text for SEO and accessibility, it is far from ideal to see that only 46.71% of mobile pages use alt attributes on all of their images. This means that there are still improvements to be made with regard to making images across the web more accessible to users and understandable for search engines. Learn more about issues like these in the Accessibility chapter.

Indexability

To show a page’s content to users in the SERPs, search engine crawlers must first be permitted to access and index that page. Some of the factors that impact a search engine’s ability to crawl and index pages include:

- Status codes

noindextags- Canonical tags

- The

robots.txtfile

Status codes

It is recommended to maintain a 200 OK status code for any important pages that you want search engines to index. The majority of pages tested were available for search engines to access, with 87.03% of initial HTML requests on desktop returning a 200 status code. The results were slightly lower for mobile pages, with only 82.95% of pages returning a 200 status code.

The next most commonly found status code on mobile was 302, a temporary redirect, which was found on 10.45% of mobile pages. This was higher than on desktop, with only 6.71% desktop home pages returning a 302 status code. This could be due to the fact that the mobile home pages were alternates to an equivalent desktop page, such as on non-responsive sites that have separate versions of the website for each device.

noindex

A noindex directive can be served in the HTML <head> or in the HTTP headers as an X-Robots directive. A noindex directive basically tells a search engine not to include that page in its SERPs, but the page will still be accessible for users when they are navigating through the website. noindex directives are usually added to duplicate versions of pages that serve the same content, or low quality pages that provide no value to users coming to a website from organic search, such as filtered, faceted, or internal search pages.

96.93% of mobile pages passed the Lighthouse indexing audit, meaning that these pages didn’t contain a noindex directive. However, this means that 3.07% of mobile home pages did have a noindex directive, which is cause for concern, meaning that Google was prevented from indexing these pages.

Canonicalization

Canonical tags are used to specify duplicate pages and their preferred alternates, so that search engines can consolidate authority which might be spread across multiple pages within the group onto one main page for improved rankings.

48.34% of mobile home pages were detected to have a canonical tag. Self-referencing canonical tags aren’t essential, and canonical tags are usually required for duplicate pages. Home pages are rarely duplicated anywhere else across the site so seeing that less than half of pages have a canonical tag isn’t surprising.

robots.txt

One of the most effective methods for controlling search engine crawling is the robots.txt file. This is a file that sits on the root domain of a website and specifies which URLs and URL paths should be disallowed from being crawled by search engines.

It was interesting to observe that only 72.16% of mobile sites have a valid robots.txt, according to Lighthouse. The key issues we found are split between 22% of sites having no robots.txt file at all, and ~6% serving an invalid robots.txt file, and thus failing the audit. While there are many valid reasons to not have a robots.txt file, such as having a small website that doesn’t struggle with crawl budget issues, having an invalid robots.txt is cause for concern.

Linking

One of the most important attributes of a web page is links. Links help search engines discover new, relevant pages to add to their index and navigate through websites. 96% of the web pages in our dataset contain at least one internal link, and 93% contain at least one external link to another domain. The small minority of pages that don’t have any internal or external links will be missing out on the immense value that links pass through to target pages.

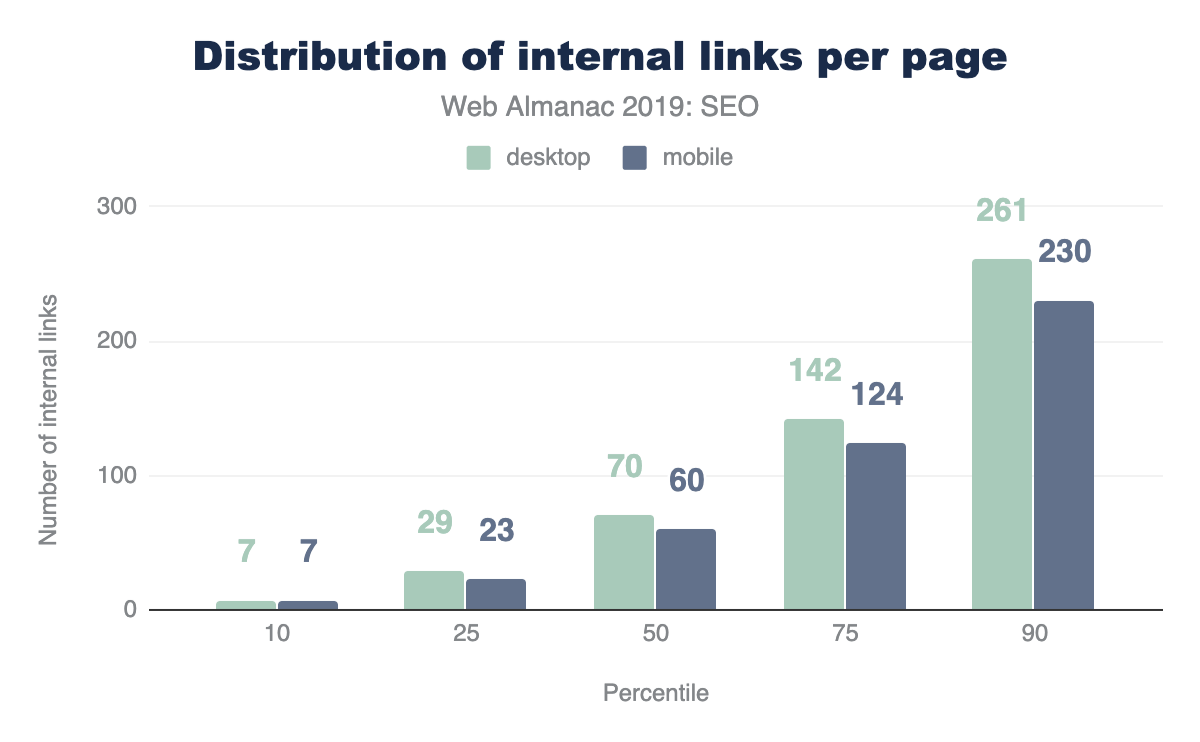

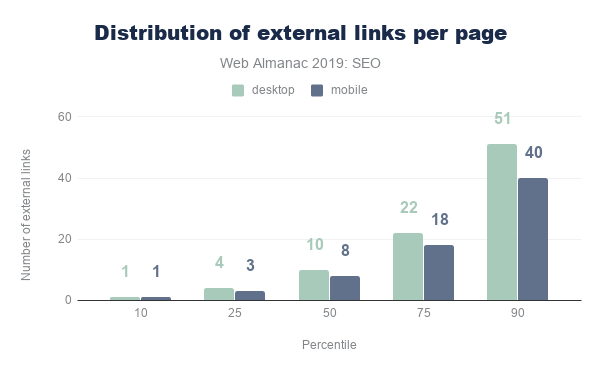

The number of internal and external links included on desktop pages were consistently higher than the number found on mobile pages. Often a limited space on a smaller viewport causes fewer links to be included in the design of a mobile page compared to desktop.

It’s important to bear in mind that fewer internal links on the mobile version of a page might cause an issue for your website. With mobile-first indexing, which for new websites is the default for Google, if a page is only linked from the desktop version and not present on the mobile version, search engines will have a much harder time discovering and ranking it.

The median desktop page includes 70 internal (same-site) links, whereas the median mobile page has 60 internal links. The median number of external links per page follows a similar trend, with desktop pages including 10 external links, and mobile pages including 8.

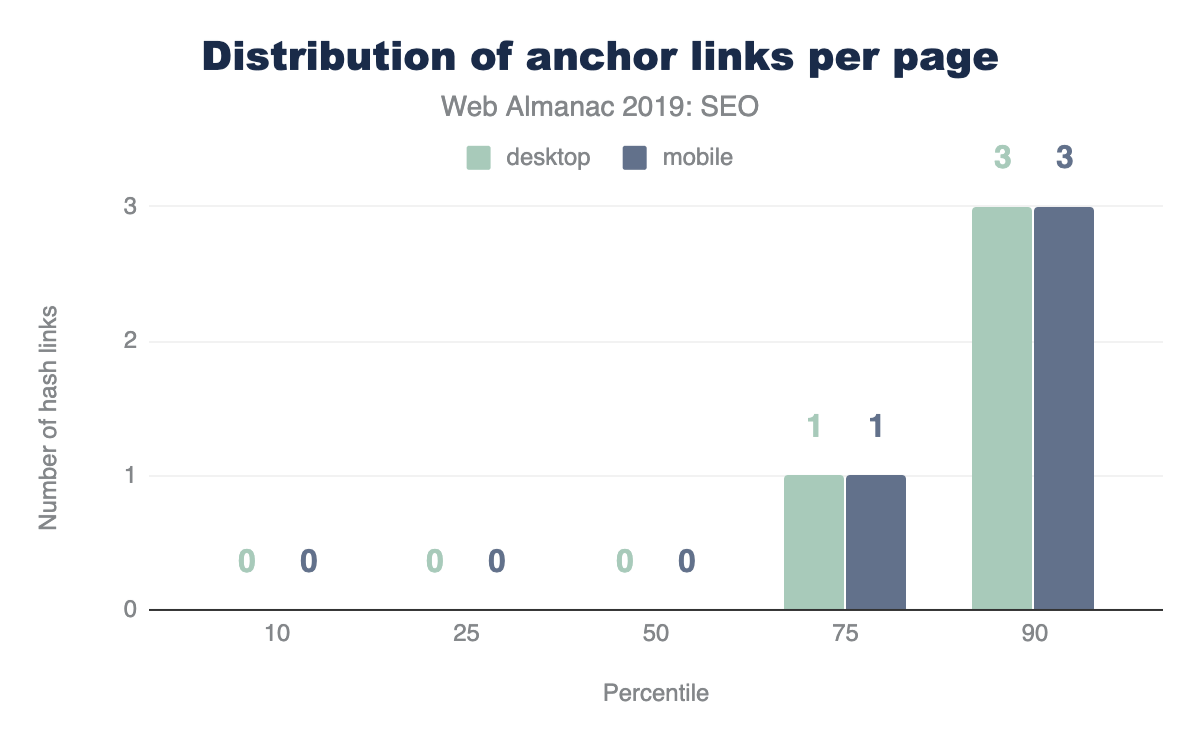

Anchor links, which link to a certain scroll position on the same page, are not very popular. Over 65% of home pages have no anchor links. This is probably due to the fact that home pages don’t usually contain any long-form content.

There is good news from our analysis of the descriptive link text metric. 89.94% of mobile pages pass Lighthouse’s descriptive link text audit. This means that these pages don’t have generic “click here”, “go”, “here” or “learn more” links, but use more meaningful link text which helps users and search engines better understand the context of pages and how they connect with one another.

Advanced

Having descriptive, useful content on a page that isn’t being blocked from search engines with a noindex or Disallow directive isn’t enough for a website to succeed in organic search. Those are just the basics. There is a lot more than can be done to enhance the performance of a website and its appearance in SERPs.

Some of the more technically complex aspects that have been gaining importance in successfully indexing and ranking websites include speed, structured data, internationalization, security, and mobile friendliness.

Speed

Mobile loading speed was first announced as a ranking factor by Google in 2018. Speed isn’t a new focus for Google though. Back in 2010 it was revealed that speed had been introduced as a ranking signal.

A fast-loading website is also crucial for a good user experience. Users that have to wait even a few seconds for a site to load have the tendency to bounce and try another result from one of your SERP competitors that loads quickly and meets their expectations of website performance.

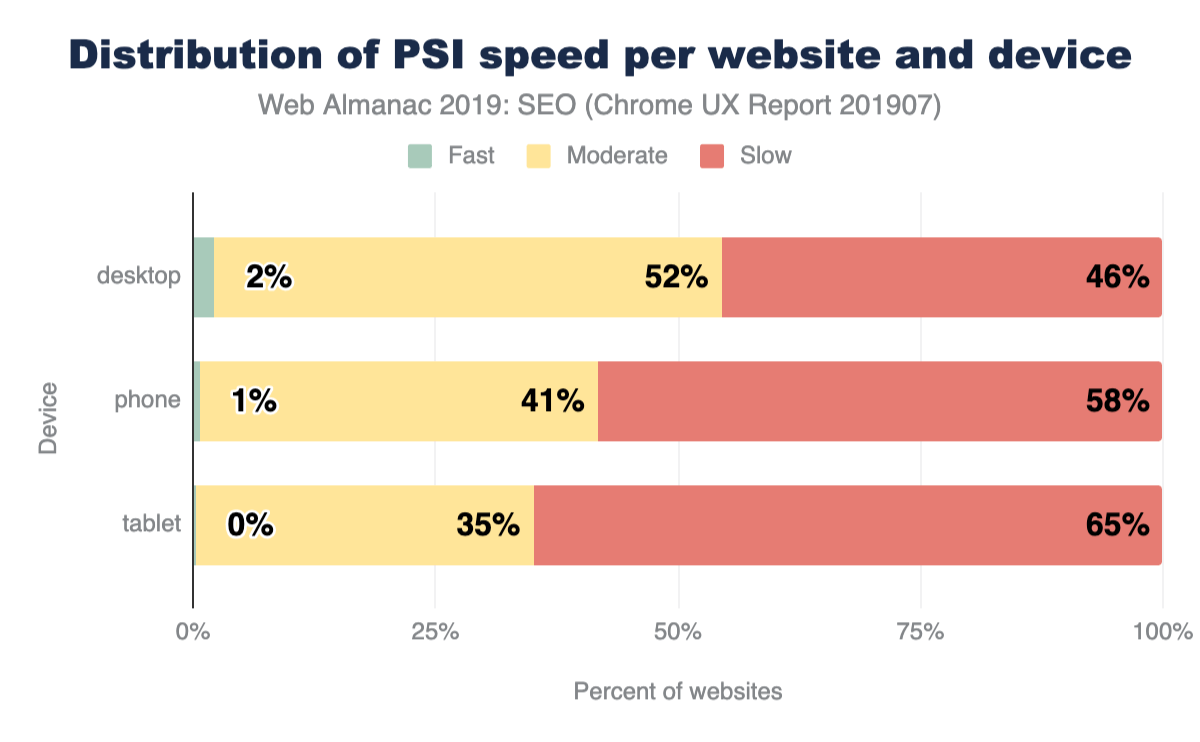

The metrics we used for our analysis of load speed across the web is based on the Chrome UX Report (CrUX), which collects data from real-world Chrome users. This data shows that an astonishing 48% of websites are labeled as slow. A website is labeled slow if it more than 25% of FCP experiences slower than 3 seconds or 5% of FID experiences slower than 300 ms.

Split by device, this picture is even bleaker for tablet (65%) and phone (58%).

Although the numbers are bleak for the speed of the web, the good news is that SEO experts and tools have been focusing more and more on the technical challenges of speeding up websites. You can learn more about the state of web performance in the Performance chapter.

Structured data

Structured data allows website owners to add additional semantic data to their web pages, by adding JSON-LD snippets or Microdata, for example. Search engines parse this data to better understand these pages and sometimes use the markup to display additional relevant information in the search results. Some of the useful types of structured data are:

- reviews

- products

- businesses

- movies

- and you can search for more types of supported structured data types

The extra visibility that structured data can provide for websites is interesting for site owners, given that it can help to create more opportunities for traffic. For example, the relatively new FAQ schema will double the size of your snippet and the real estate of your site in the SERP.

During our research, we found that only 14.67% of sites are eligible for rich results on mobile. Interestingly, desktop site eligibility is slightly lower at 12.46%. This suggests that there is a lot more that site owners can be doing to optimize the way their home pages are appearing in search.

Among the sites with structured data markup, the five most prevalent types are:

WebSite(16.02%)SearchAction(14.35%)Organization(12.89%)WebPage(11.58%)ImageObject(5.35%)

Interestingly, one of the most popular data types that triggers a search engine feature is SearchAction, which powers the sitelinks searchbox.

The top five markup types all lead to more visibility in Google’s search results, which might be the fuel for more widespread adoption of these types of structured data.

Seeing as we only looked at home pages within this analysis, the results might look very different if we were to consider interior pages, too.

Review stars are only found on 1.09% of the web’s home pages (via AggregateRating). Also, the newly introduced QAPage appeared only in 48 instances, and the FAQPage at a slightly higher frequency of 218 times. These last two counts are expected to increase in the future as we run more crawls and dive deeper into Web Almanac analysis.

Internationalization

Internationalization is one of the most complex aspects of SEO, even according to some Google search employees. Internationalization in SEO focuses on serving the right content from a website with multiple language or country versions and making sure that content is being targeted towards the specific language and location of the user.

While 38.40% of desktop sites (33.79% on mobile) have the HTML lang attribute set to English, only 7.43% (6.79% on mobile) of the sites also contain an hreflang link to another language version. This suggests that the vast majority of websites that we analyzed don’t offer separate versions of their home page that would require language targeting -- unless these separate versions do exist but haven’t been configured correctly.

hreflang |

Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| en | 12.19% | 2.80% |

| x-default | 5.58% | 1.44% |

| fr | 5.23% | 1.28% |

| es | 5.08% | 1.25% |

| de | 4.91% | 1.24% |

| en-us | 4.22% | 2.95% |

| it | 3.58% | 0.92% |

| ru | 3.13% | 0.80% |

| en-gb | 3.04% | 2.79% |

| de-de | 2.34% | 2.58% |

| nl | 2.28% | 0.55% |

| fr-fr | 2.28% | 2.56% |

| es-es | 2.08% | 2.51% |

| pt | 2.07% | 0.48% |

| pl | 2.01% | 0.50% |

| ja | 2.00% | 0.43% |

| tr | 1.78% | 0.49% |

| it-it | 1.62% | 2.40% |

| ar | 1.59% | 0.43% |

| pt-br | 1.52% | 2.38% |

| th | 1.40% | 0.42% |

| ko | 1.33% | 0.28% |

| zh | 1.30% | 0.27% |

| sv | 1.22% | 0.30% |

| en-au | 1.20% | 2.31% |

hreflang values.

Next to English, the most common languages are French, Spanish, and German. These are followed by languages targeted towards specific geographies like English for Americans (en-us) or more obscure combinations like Spanish for the Irish (es-ie).

The analysis did not check for correct implementation, such as whether or not the different language versions properly link to each other. However, from looking at the low adoption of having an x-default version (only 3.77% on desktop and 1.30% on mobile), as is recommended, this is an indicator that this element is complex and not always easy to get right.

SPA crawlability

Single-page applications (SPAs) built with frameworks like React and Vue.js come with their own SEO complexity. Websites using a hash-based navigation, make it especially hard for search engines to properly crawl and index them. For example, Google had an “AJAX crawling scheme” workaround that turned out to be complex for search engines as well as developers, so it was deprecated in 2015.

The number of SPAs that were tested had a relatively low number of links served via hash URLs, with 13.08% of React mobile pages using hash URLs for navigation, 8.15% of mobile Vue.js pages using them, and 2.37% of mobile Angular pages using them. These results were very similar for desktop pages too. This is positive to see from an SEO perspective, considering the impact that hash URLs can have on content discovery.

The higher number of hash URLs in React pages is surprising, especially in contrast to the lower number of hash URLs found on Angular pages. Both frameworks promote the adoption of routing packages where the History API is the default for links, instead of relying on hash URLs. Vue.js is considering moving to using the History API as the default as well in version 3 of their vue-router package.

AMP

AMP (formerly known as “Accelerated Mobile Pages”) was first introduced in 2015 by Google as an open source HTML framework. It provides components and infrastructure for websites to provide a faster experience for users, by using optimizations such as caching, lazy loading, and optimized images. Notably, Google adopted this for their search engine, where AMP pages are also served from their own CDN. This feature later became a standards proposal under the name Signed HTTP Exchanges.

Despite this, only 0.62% of mobile home pages contain a link to an AMP version. Given the visibility this project has had, this suggests that it has had a relatively low adoption. However, AMP can be more useful for serving article pages, so our home page-focused analysis won’t reflect adoption across other page types.

Security

A strong online shift in recent years has been for the web to move to HTTPS by default. HTTPS prevents website traffic from being intercepted on public Wi-Fi networks, for example, where user input data is then transmitted unsecurely. Google have been pushing for sites to adopt HTTPS, and even made HTTPS as a ranking signal. Chrome also supported the move to secure pages by labeling non-HTTPS pages as not secure in the browser.

For more information and guidance from Google on the importance of HTTPS and how to adopt it, please see Why HTTPS Matters.

We found that 67.06% of websites on desktop are now served over HTTPS. Just under half of websites still haven’t migrated to HTTPS and are serving non-secure pages to their users. This is a significant number. Migrations can be hard work, so this could be a reason why the adoption rate isn’t higher, but an HTTPS migration usually require an SSL certificate and a simple change to the .htaccess file. There’s no real reason not to switch to HTTPS.

Google’s HTTPS Transparency Report reports a 90% adoption of HTTPS for the top 100 non-Google domains (representing 25% of all website traffic worldwide). The difference between this number and ours could be explained by the fact that relatively smaller sites are adopting HTTPS at a slower rate.

Learn more about the state of security in the Security chapter.

Conclusion

Through our analysis, we observed that the majority of websites are getting the fundamentals right, in that their home pages are crawlable, indexable, and include the key content required to rank well in search engines’ results pages. Not every person who owns a website will be aware of SEO at all, let alone its best practice guidelines, so it is promising to see that so many sites have got the basics covered.

However, more sites are missing the mark than expected when it comes to some of the more advanced aspects of SEO and accessibility. Site speed is one of these factors that many websites are struggling with, especially on mobile. This is a significant problem, as speed is one of the biggest contributors to UX, which is something that can impact rankings. The number of websites that aren’t yet served over HTTPS is also problematic to see, considering the importance of security and keeping user data safe.

There is a lot more that we can all be doing to learn about SEO best practices and industry developments. This is essential due to the evolving nature of the search industry and the rate at which changes happen. Search engines make thousands of improvements to their algorithms each year, and we need to keep up if we want our websites to reach more visitors in organic search.