CDN

Introduction

This chapter provides insights regarding the current state of CDN usage. CDNs are playing an increasingly important role in delivering content to users around the globe—even for smaller sites by facilitating the delivery of static and third-party content such as JavaScript libraries, Fonts and other content. Another key aspect of the CDNs that we will discuss in this chapter is the role CDNs play in adoption of new standards such as TLS and HTTP versions.

We think that CDNs will continue play a vital role in the future not just for content delivery but for content security as well. We recommend that users look at CDNs from both a performance and a security viewpoint.

What is a CDN?

A Content Delivery Network (CDN) is a geographically distributed network of proxy servers. The goal of a CDN is to provide high availability and performance for web content. It does this by distributing content closer to the end users as well as supporting advanced technologies to delivery content optimally.

Due to the explosion of web content such as videos and images, CDN has been a vital part of many websites to provide a smooth user experience. Post COVID-19, the need for CDN has only increased due to many brick and mortar businesses moving online, increase in web conferencing, online gaming and video streaming.

During the early days, a CDN was a simple network of proxy servers which would:

- Cache content (like HTML, images, stylesheets, JavaScript, videos, etc.)

- Reduce network hops for end users to access content

- Offload TCP connection termination away from the data centers hosting the web properties

They primarily helped web owners to improve the page load times and to offload traffic from the infrastructure hosting these web properties.

Over time, the services offered by CDN providers have evolved beyond caching and offloading bandwidth/connections. Due to its distributed nature and large distributed network capacity CDNs have proved to be extremely efficient at handling large scale Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks. Edge computing is another service that has gained popularity in the recent years. Many CDN vendors provide compute services at the edge that allows the web owners to run simple code at the edge.

Other services offered by the CDN vendors include:

- Cloud-hosted Web Application Firewalls (WAF)

- Bot Management solutions

- Clean pipe solutions (Scrubbing Data-centers)

- Image and video management solutions

There are benefits to web owners in pushing web application logic and workflows closer to the end user. This eliminates the round trip and bandwidth that a HTTP/HTTPS request would take. It also handles near-instant scalability requirements for the origin. A side-effect of this is that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) benefit from the scalability management as well, which improves their infrastructure capacities.

Caveats and disclaimers

As with any observational study, there are limits to the scope and impact that can be measured. The statistics gathered on CDN usage for the Web Almanac are focused more on applicable technologies in use and not intended to measure performance or effectiveness of a specific CDN vendor. While this ensures that we are not biased towards any CDN vendor, it also means that these are more generalized results.

These are the limits to our testing methodology:

-

Simulated network latency: We use a dedicated network connection that synthetically shapes traffic.

-

Single geographic location: Tests are run from a single datacenter and cannot test the geographic distribution of many CDN vendors.

-

Cache effectiveness: Each CDN uses proprietary technology and many, for security reasons, do not expose cache performance.

-

Localization and internationalization: Just like geographic distribution, the effects of language and geo-specific domains are also opaque to these tests.

-

CDN detection: This is primarily done through DNS resolution and HTTP headers. Most CDNs use a DNS CNAME to map a user to an optimal data center. However, some CDNs use Anycast IPs or direct A+AAAA responses from a delegated domain which hide the DNS chain. In other cases, websites use multiple CDNs to balance between vendors, which is hidden from the single-request pass of our crawler.

All of this influences our measurements.

Most importantly, these results reflect the support of specific features (for example TLSv1.3, HTTP/2) per site, but do not reflect actual traffic usage. YouTube is more popular than www.example.com yet both will appear as equal in our dataset.

With this in mind, here are a few statistics that were intentionally not measured in the context of a CDN:

- Time To First Byte (TTFB)

- CDN Round Trip Time

- Core Web Vitals

- “Cache hit” versus “cache miss” performance

While some of these could be measured with HTTP Archive dataset, and others by using the CrUX dataset, the limitations of our methodology and the use of multiple CDNs by some sites, will be difficult to measure and so could be incorrectly attributed. For these reasons, we have decided not to measure these statistics in this chapter.

We did not see any notable differences between mobile and desktop so, to avoid repeating ourselves, the data provided in this chapter is primarily for mobile usage unless otherwise noted.

CDN adoption

A web page is composed of following key components:

- Base HTML page (for example,

www.example.com/index.html—often available at a more friendly name like justwww.example.com). - Embedded first-party content such as images, css, fonts and javascript files on the main domain (

www.example.com) and the subdomains (for example,images.example.com, orassets.example.com). - Third-party content (for example, Google Analytics, advertisements) served from third-party domains.

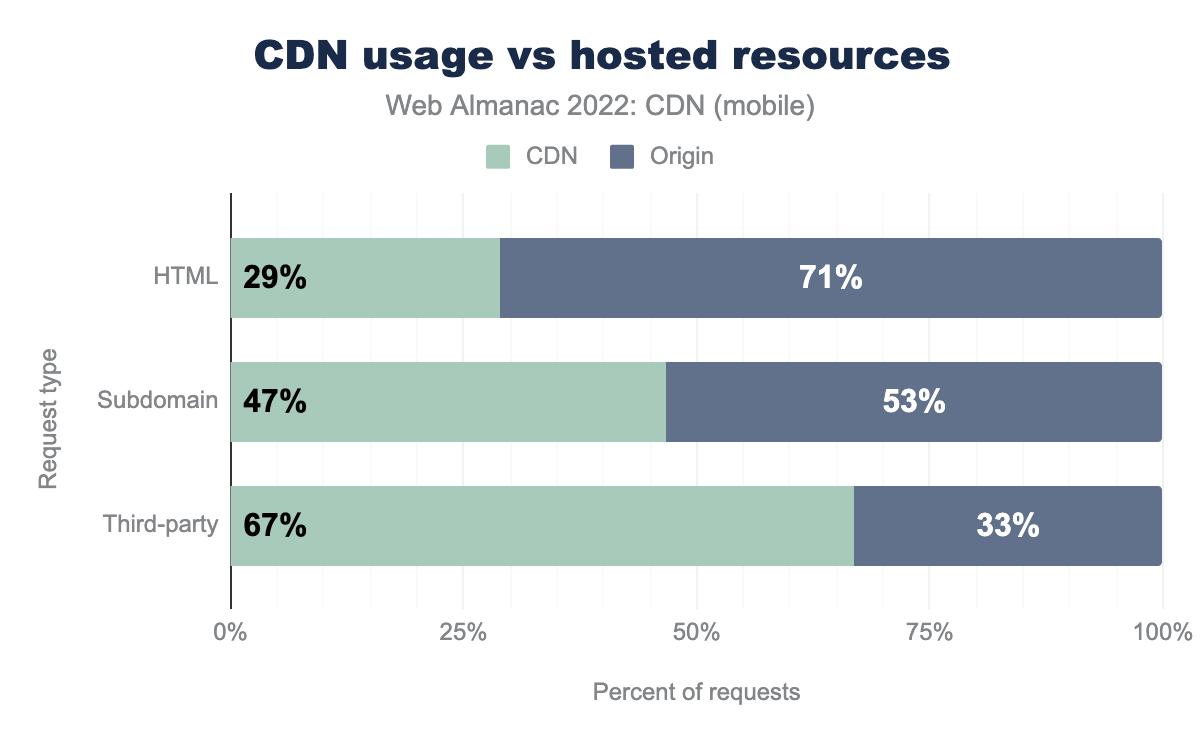

The above chart shows the split of each type of request for CDNs versus hosted resources for mobile—as mentioned in the introduction almost identical figures were seen for desktop. We see CDNs are often utilized for delivering static content such as images, stylesheets, JavaScript, and fonts. This kind of content doesn’t change frequently, making it a good candidate for caching on a CDNs proxy servers. We still see CDNs are used more frequently for this type of resource–especially for third-party content.

CDNs can provide better performance for delivering non-static content as well as they often optimize the routes and use most efficient transport mechanisms, but we see the usage of serving the HTML still lags considerably behind the other two types.

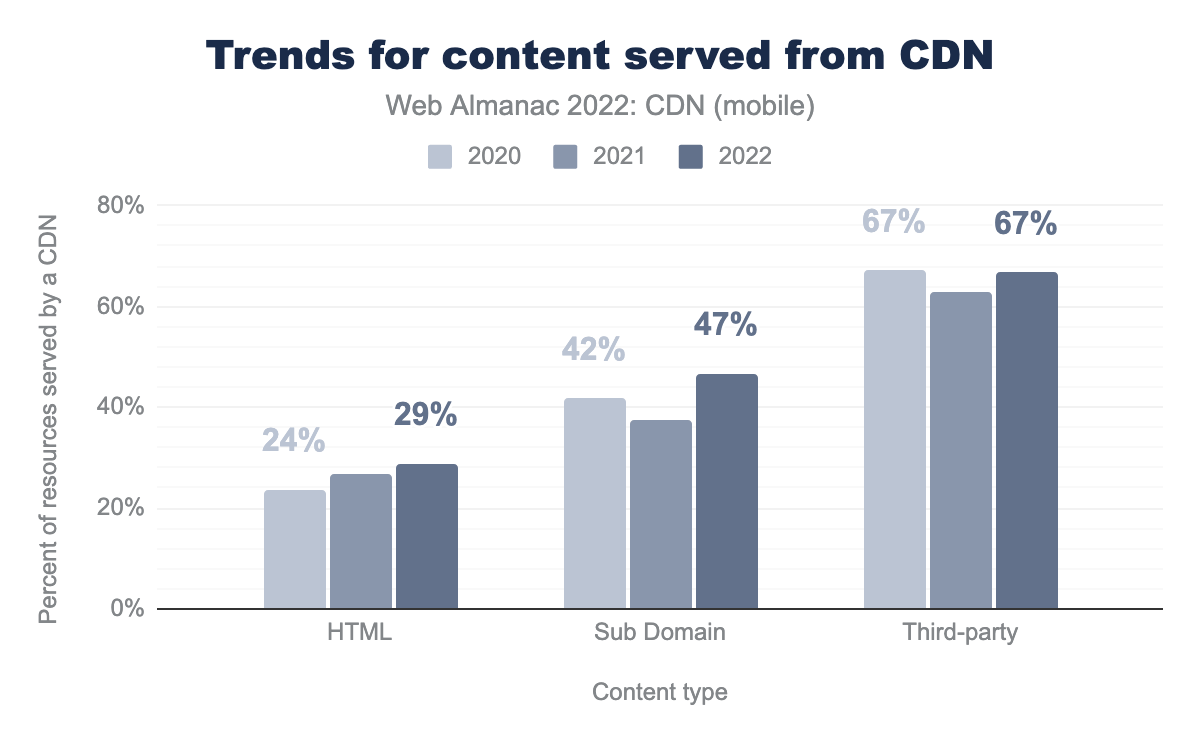

Compared to the year 2021 we found that the usage of CDN has been steadily increasing. There was a large bump in CDN usage for the content served from subdomains, and a smaller one for HTML while third-party CDN usage remained relatively static.

These are some of the potential reasons that can be attributed to this rise:

- Post pandemic, many businesses took a large portion of their physical business online. This put a lot of strain on their servers and found that it was much more efficient to server the static content through CDNs for offloading through caching and faster delivery.

- This increase was not seen in 2021 as many businesses were still trying to figure out the optimal solution for their problem. In fact we saw a dip in CDN usage for the subdomain and third-party type.

- Sites relied on serving third-party content through third-party domains instead of their own domains. The fact that the amount of content served from third-party domains increased by 3% during this period supports this assumption.

Regarding the base HTML page, the traditional pattern has been to serve the base HTML from the origin and this pattern has continued as majority of base pages continue to be served from the origin. However, there has been a 4% increase in the base pages being served from CDNs. The trend of base HTML pages being served from the CDN is clearly on the rise.

These are some of the likely reasons behind the rise:

- CDNs can improve load time of the base HTML page that can be of high importance to improve customer experience and keep users engaged.

- Using distributed DNS from by CDN providers is simpler and faster.

- It is easier to plan Disaster Recovery if most of the content including the base HTML page is pushed through CDNs. CDNs often provide a failover functionality to automatically switch to the alternative site once the primary site becomes unstable or unavailable.

While we observed CDN adoption across different types of content, we will look at this data from a different point of view below—based on the site popularity.

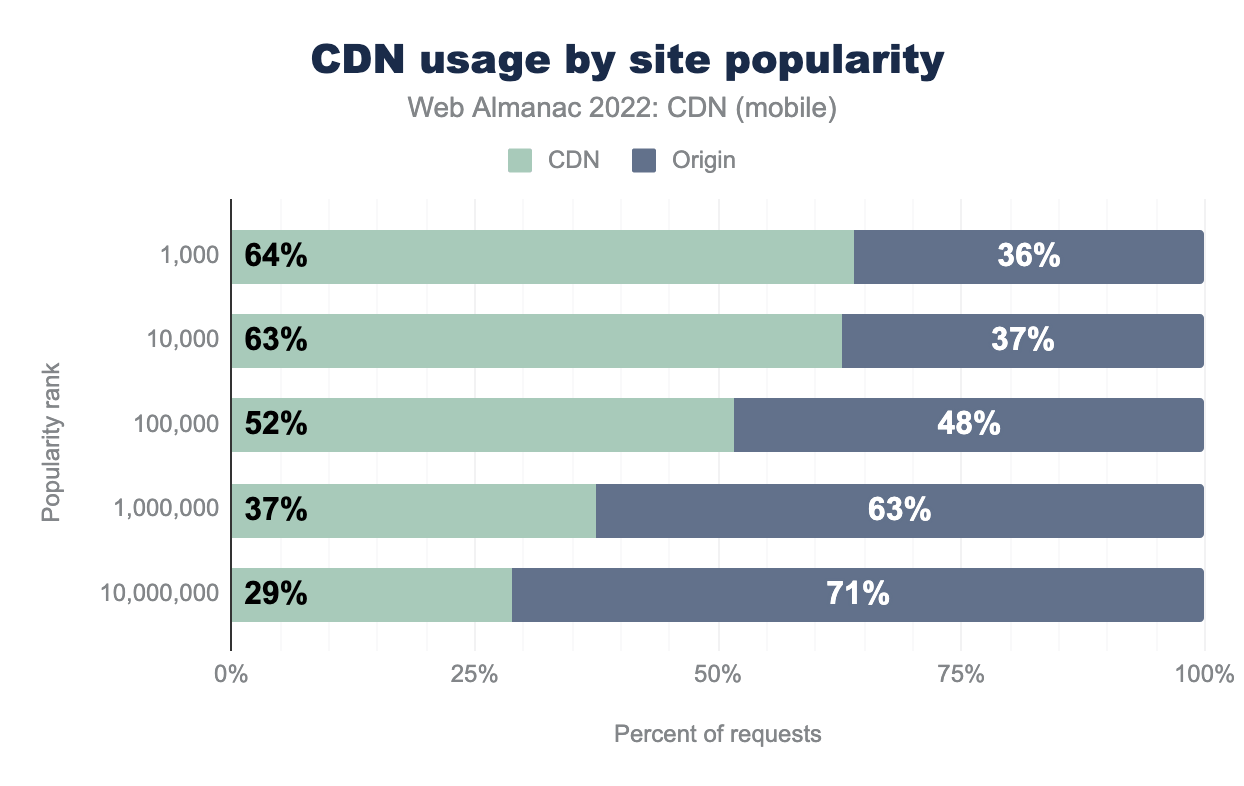

Looking at CDN usage for websites based on their popularity—sourced from Google’s Chrome UX Report—the top 1,000-10,000 contribute to the highest usage of CDN. For the high ranked sites, it is understandable that owner companies are investing in CDN for performance and other benefits but even for the top 1,000,000 sites, there has been about a 7% increase in the amount of content delivered through CDNs compared to 2021. This increase in CDN usage for lower popularity sites can be attributed to the fact that there has been an increase in free and affordable options for CDNs and many hosting solutions have CDNs bundled with the services.

Top CDN providers

CDN providers can be broadly classified into 2 segments:

- Generic CDN (Akamai, Cloudflare, CloudFront, Fastly, etc.)

- Purpose-built CDN (Netlify, WordPress, etc.)

Generic CDNs address the mass market requirements. Their offerings include:

- Web site delivery

- Mobile app API delivery

- Video streaming

- Edge computing services

- Web security offerings

This appeals to a larger set of industries and is reflected in the data.

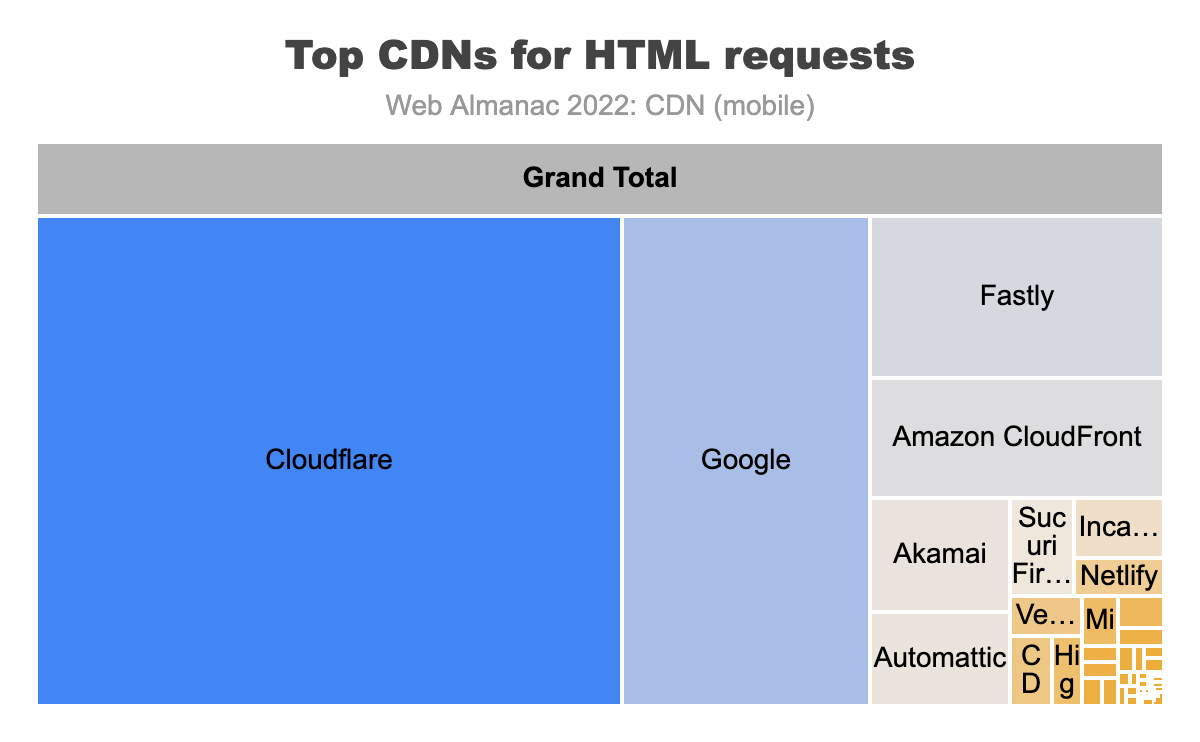

The above figure shows the top CDN providers for base HTML requests. The top vendors in this category are Cloudflare, Google, Fastly Amazon CloudFront, Akamai and Atomattic.

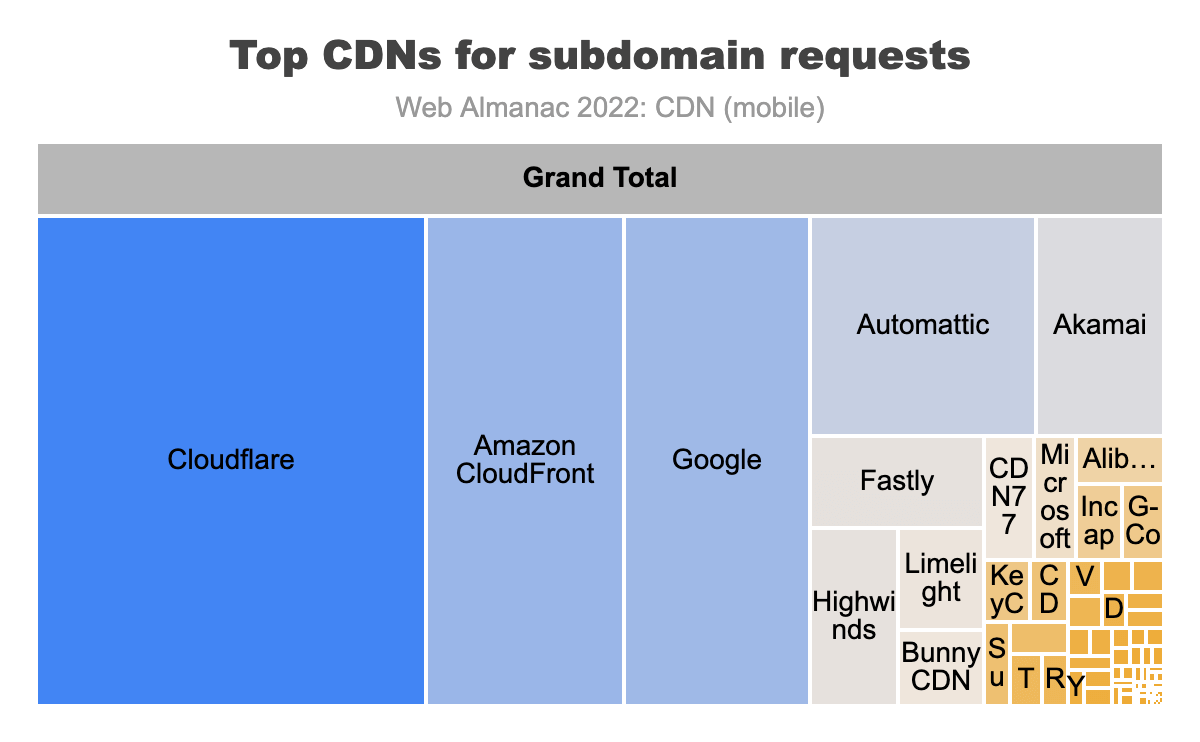

For the subdomain requests we can see greater usage of providers like Amazon and Google. This is because many users have their content hosted in the cloud services they provide and the users utilize CDN offerings along with their cloud services. This helps the users to scale their applications and increase the performance of their application.

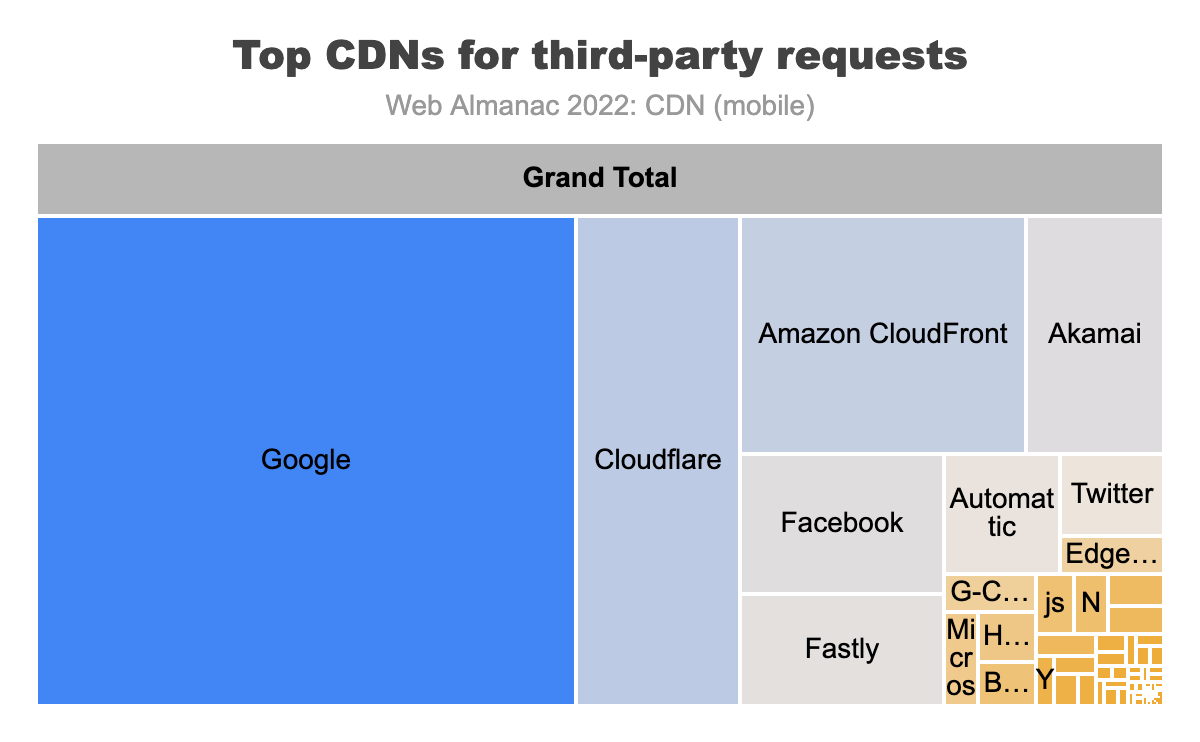

Looking at third-party domains, a different trend in top CDN providers is seen. We see Google top the list before the generic CDN providers. The list also brings Facebook into prominence. This is backed by the fact that a lot of third-party domain owners require CDNs more than other industries. For the larger third-party providers—like Google, like Facebook—this necessitates them to invest in building a purpose-built CDN. A purpose-built CDN is one which is optimized for a particular content delivery workflow.

For example, a CDN built specifically to deliver advertisements will be optimized for:

- High input-output (I/O) operations

- Effective management of long tail content

- Geographical closeness to businesses requiring their services

This means purpose-built CDNs meet the exact requirements of a particular market segment as opposed to a generic CDN solution. Generic solutions can meet a broader set of requirements but are not optimized for any particular industry or market.

TLS usage

With CDNs set up in the request-response workflows, the end-user’s TLS connection terminates at the CDN. In turn, the CDN sets up a second independent TLS connection and this connection goes from the CDN to the origin host. This break in the CDN workflow allows the CDN to define the end-user’s TLS parameters. CDNs tend to also provide automatic updates to internet protocols. This allows web owners to receive these benefits without making changes to their origin.

TLS adoption impact

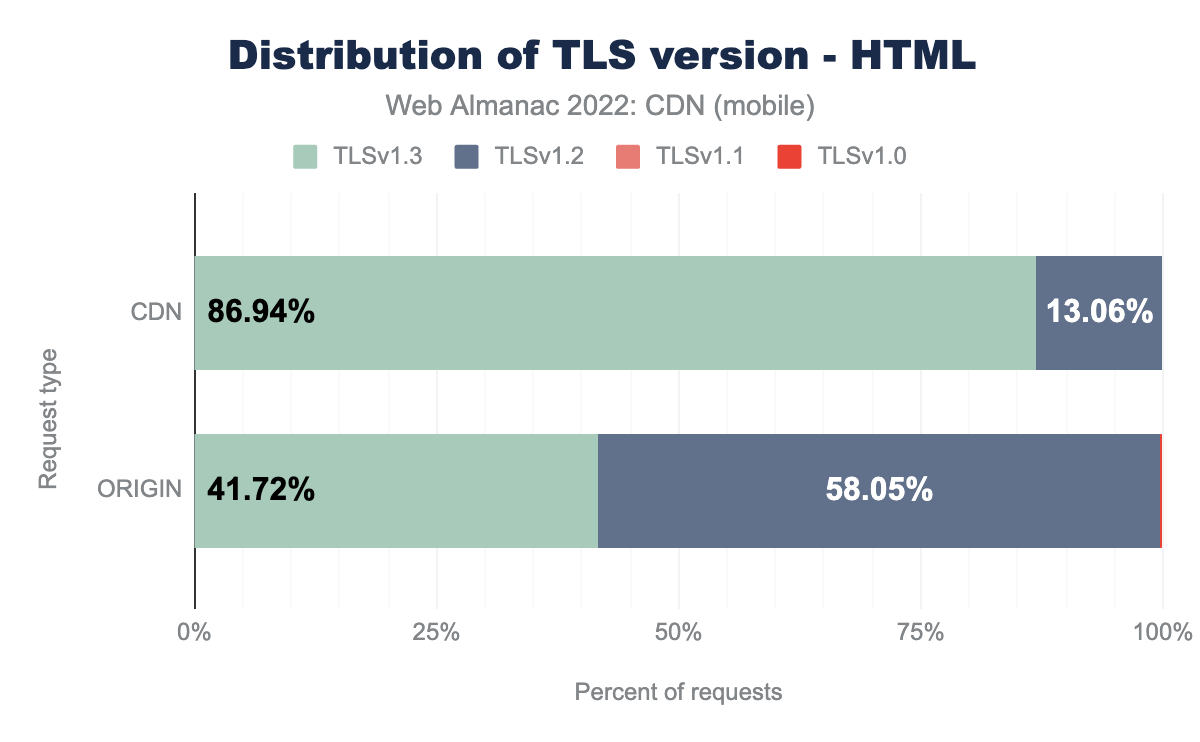

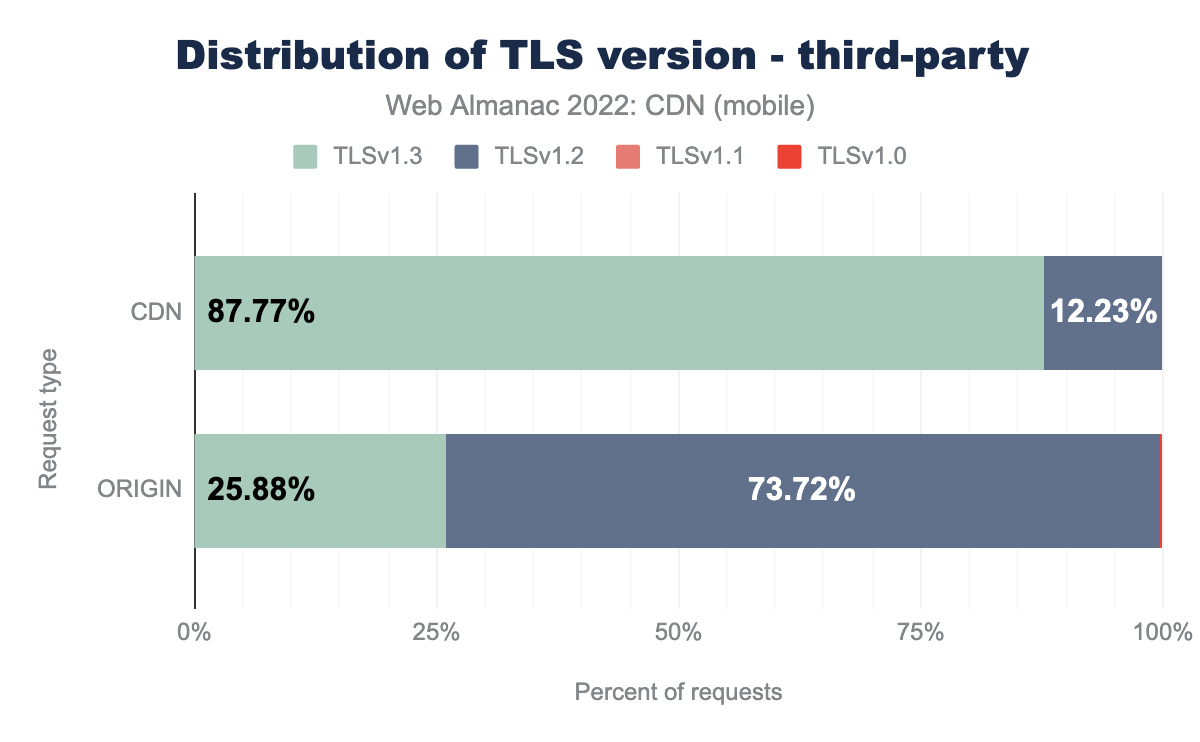

The charts below show that the adoption of the latest version of TLS has been much higher for the content served from CDN compared to origin

Compared to the year 2021, for mobile HTML content the adoption of TLS v1.3 has increased by 5% while for the content served from origin the TLS v1.3 adoption has increased by 10%.

In the current security landscape it is important for the content to be delivered via the latest TLS version. It can be seen from the data above that the move to TLS v1.3 was much faster for CDNs compared to the origin. This shows the added security benefit of using CDNs for content delivery.

TLS performance impact

Common logic dictates that the fewer hops it takes for a HTTPS request-response to traverse, the faster the round trip would be.

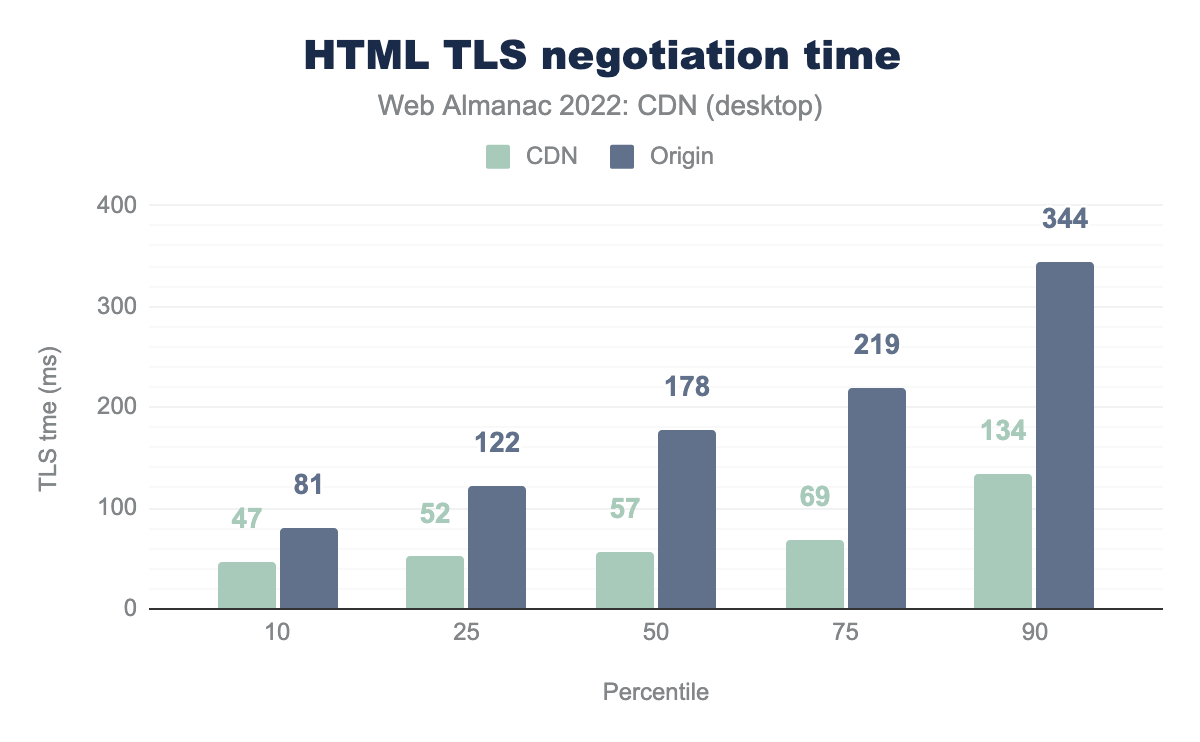

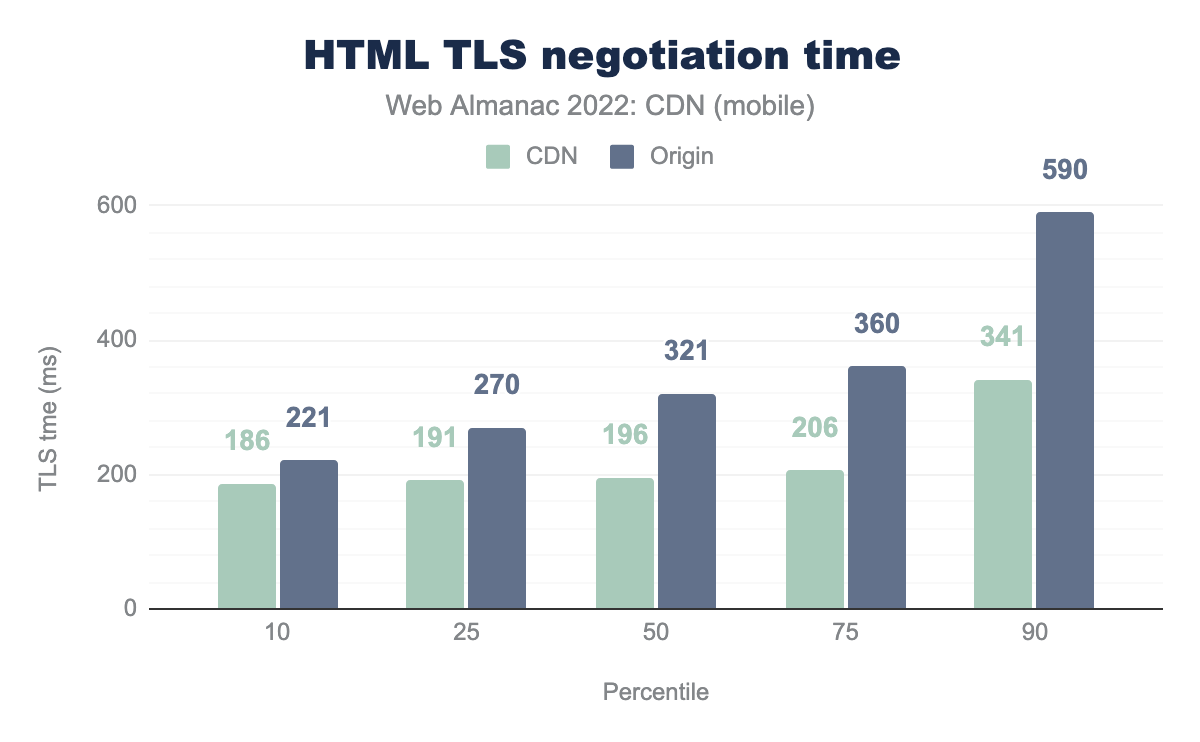

As it can be seen from the figures above, the TLS negotiation time is generally much better when with CDNs. This is even more so when comparing the desktop and mobile data, where the greater Round Trip Time (RTT) used by our mobile crawler results in much greater TLS negotiation times.

CDNs have helped slash the TLS connection times. This is due to their proximity to the end user and adoption of newer TLS protocols that optimize the TLS negotiation. CDNs hold the edge over origin at all percentiles here. At P10 and P25, CDNs are nearly 1.5x faster than origin in TLS set up time. The gap increases even more once we hit the median and above, where CDNs are nearly 2x faster (mobile) and nearly 3x faster (desktop). 90th percentile users using a CDN will have better performance than 50th percentile users on direct origin connections.

This is particularly important when you consider that all sites have to be on TLS these days. Optimal performance at this layer is essential for other steps that follow TLS connection. In this regard, CDNs are able to move more users to lower percentile brackets compared to direct origin connections.

HTTP/2+ adoption

The HTTP/2 specification was first introduced in 2015 and saw broad support with most major browsers adopting before the end of the year. The HTTP application layer protocol had not been updated since HTTP 1.1 in 1997 and since then the web traffic trend, content-type, content size, website design, platforms, mobile apps and more have evolved significantly. Thus, there was a need to have a protocol which can meet the requirements of the modern-day web traffic and that protocol was realized with HTTP/2.

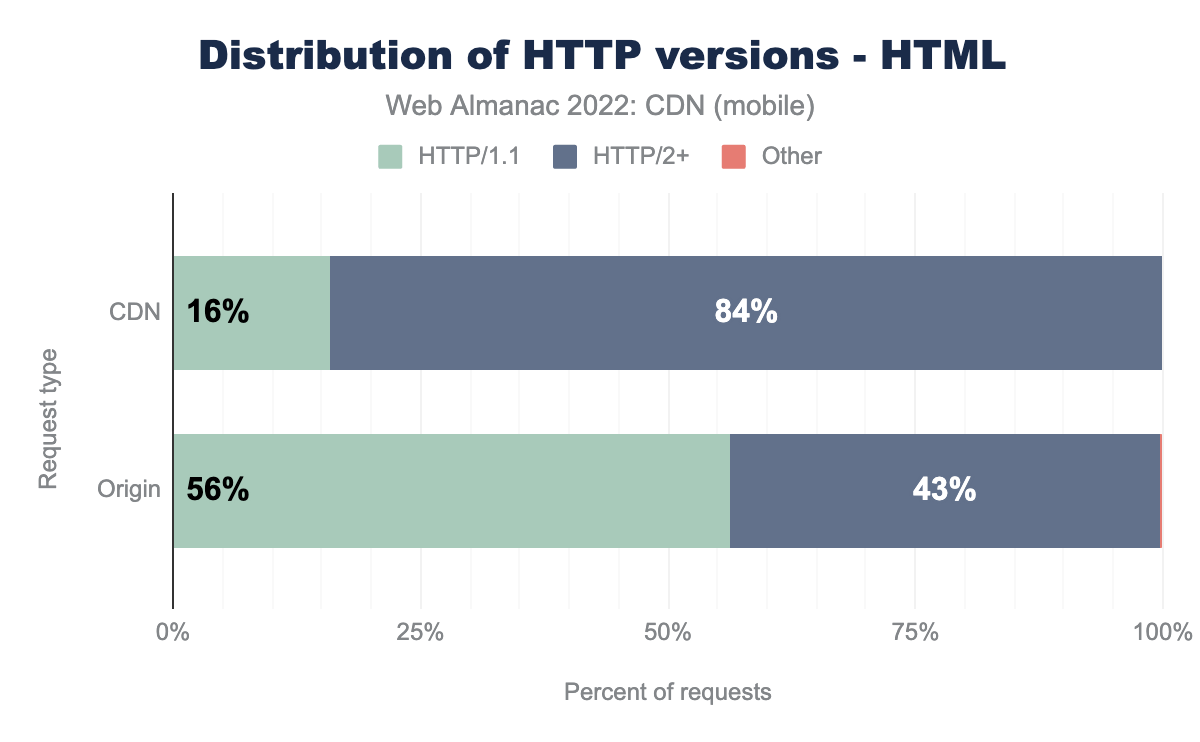

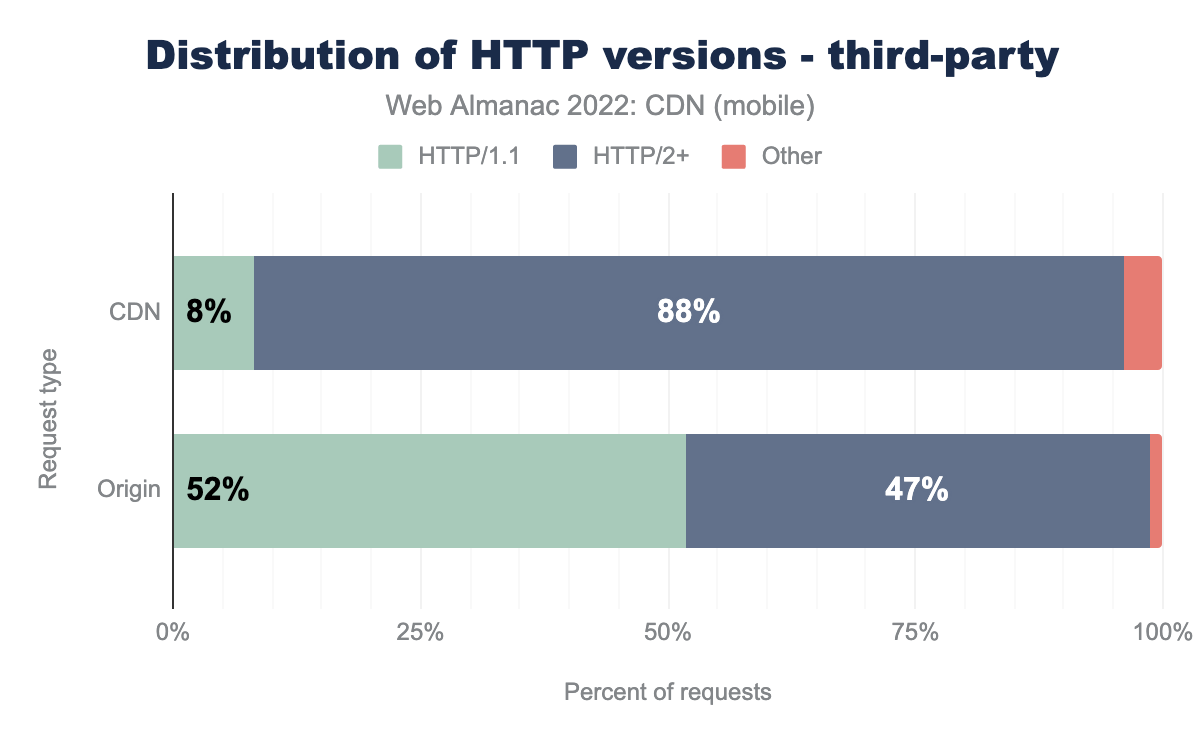

Despite the hype of HTTP/2 and the promise of reduced latency and other functionality, adoption relied on server side updates to support the newer application protocol. CDNs can help bridge the challenge of newer implementations for web owners, and this is also the case for the even newer HTTP/3 protocol. An HTTP connection terminates at the CDN level, and this provides web owners the ability to deliver their website and subdomains over HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 without the need to upgrade their own infrastructure to support it. Similar benefits were also seen with the adoption of newer TLS versions.

CDNs act as the proxy to bridge the gap by providing a layer to consolidate hostnames and route traffic to relevant endpoints with minimal change to their hosting infrastructure. Features like prioritizing content in the queue and server push can be managed from the CDNs side and a few CDNs even provide hands-off automated solutions to run these features without any inputs from website owners, thus providing a boost to HTTP/2 adoption.

There are stark contrasts in the graph above with high HTTP/2+ adoption by domains on CDNs compared to the ones not using a CDN.

In 2021 nearly 40% of the content served from origin had adopted HTTP/2 while during the same time 81% of the content served from CDNs were served through HTTP/2. For origins this number has grown by 3% points while for the CDN it has grown by 6% points—further widening the considerable gap that was already present. This shows how CDNs were able to allow the website owners to take advantage of newer protocols from very early stage without making any changes in the origin.

Third-party domains have been even quicker to support new protocols as we saw in our previous study. In 2022 we saw a further decline in the share of HTTP/1.1 for the third-party domains, though our data was unable to identify a larger number of the protocol used this year, which warrants further investigation.

Third-party domains need to have consistent performance across all network conditions, and this is where HTTP/2+ adds value. In June of 2022, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) published the HTTP/3 RFC to take the web from TCP to UDP. Many CDN providers have been quick to adopt HTTP/3 support, some before its formal RFC publication, and over time we should see web owners adopting HTTP/3, especially with mobile network traffic having a higher contribution to the total internet traffic. Stay tuned for more insights in 2023.

Brotli adoption

Content delivered over the internet employs compression to reduce the payload size. A smaller payload means it’s faster to deliver the content from server to end user. This makes websites load faster and provide a better end-user experience. For images, this compression is handled by image file formats like JPEG, WEBP, AVIF—refer to the Media chapter for more on this. For textual web assets—such as HTML, JavaScript, and stylesheets— compression was traditionally handled by the Gzip fiel format. Gzip has been in existence since 1992. It did a good job of making text asset payloads smaller, but a new text asset compression can do better than Gzip by using the newer Brotli compression format.

Similar to TLS and HTTP/2 adoption, Brotli went through a phase of gradual adoption across web platforms. At the time of this writing, Brotli is supported by over 96% of the web browsers globally. However, not all websites compress text assets in Brotli format. This is because of both lack of support and of the longer time required to compress a text asset in Brotli format compared to Gzip compression. Also, the hosting infrastructure needs to have backward compatibility to serve Gzip compressed assets for older platforms which do not support the Brotli format, which can add complexity.

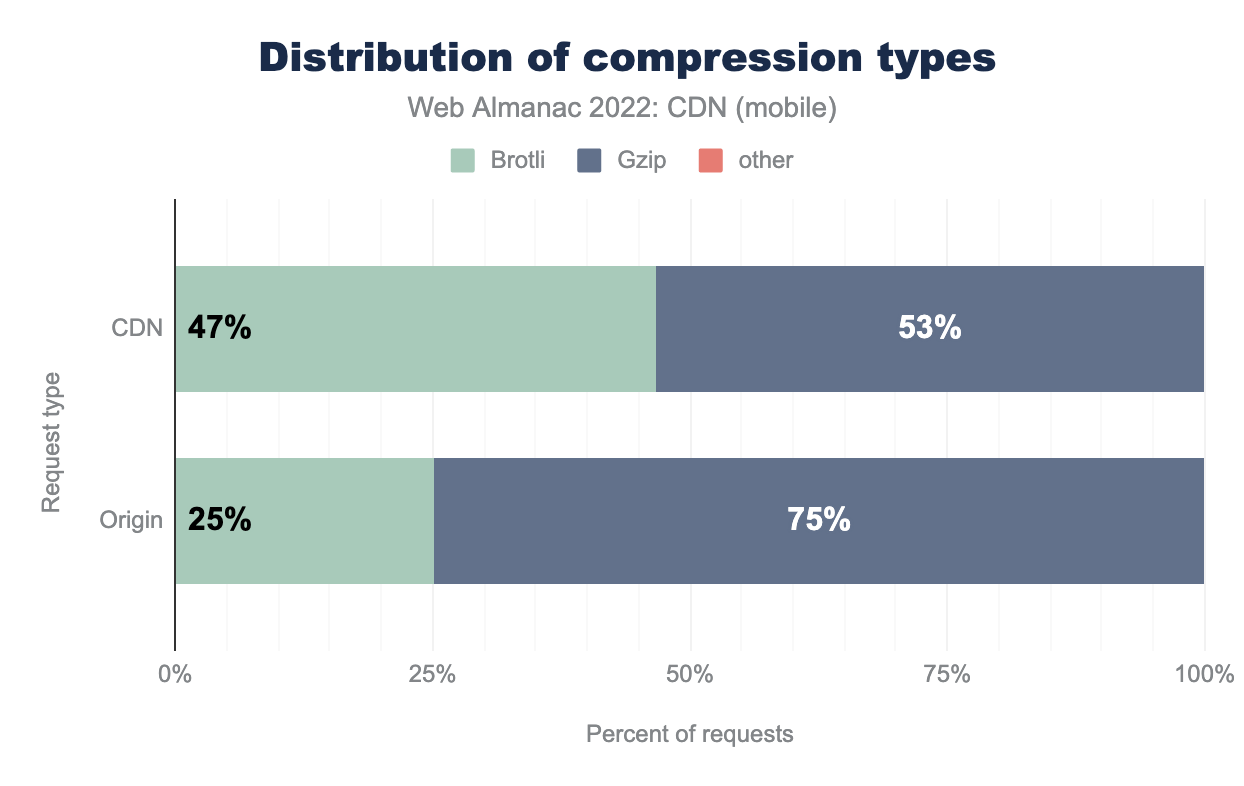

The impact of this is observed when we compare websites which are using CDN against the ones not using CDN.

Both CDN and Origin have shown an increase in adoption of Brotli compared to the previous year. We have seen the adoption of Brotli on CDN grow by 5% points while the Origin grew by almost 4% points. We will be able to see if this trend will continue in year 2023 or we have reached the saturation point.

Client Hint adoption

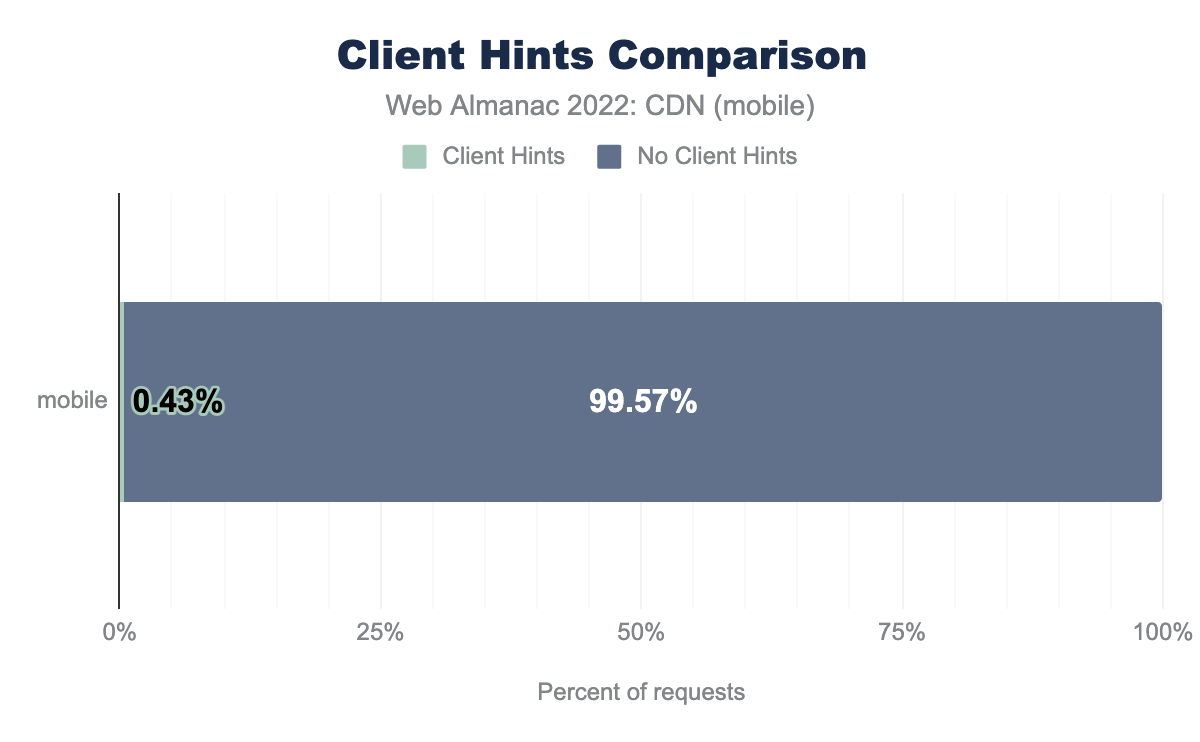

Client Hints allows a web server to proactively request data from the client and are sent as part of the HTTP headers. The client may provide information such as device, user-agent preferences and networking. Based on the provided information, the server can determine the most optimal resources to respond with to the requesting client. Client Hints were first introduced on the Google Chrome browsers and while other Chromium based browsers have adopted it, other popular browsers have limited or no support for Client Hints.

The CDN, origin servers, and client browser must all support Client Hints to be utilized properly. As part of the flow, the CDN can present the Accept-CH HTTP header to the client in order to request which Client Hints a client should include in subsequent requests. We measured clients responses where the CDN provided this header inside the request and measured it across all CDN requests recorded as part of our testing.

For both desktop and mobile clients we saw less than 1% usage of Client Hints, showing that Client Hints adoption is still in its infancy.

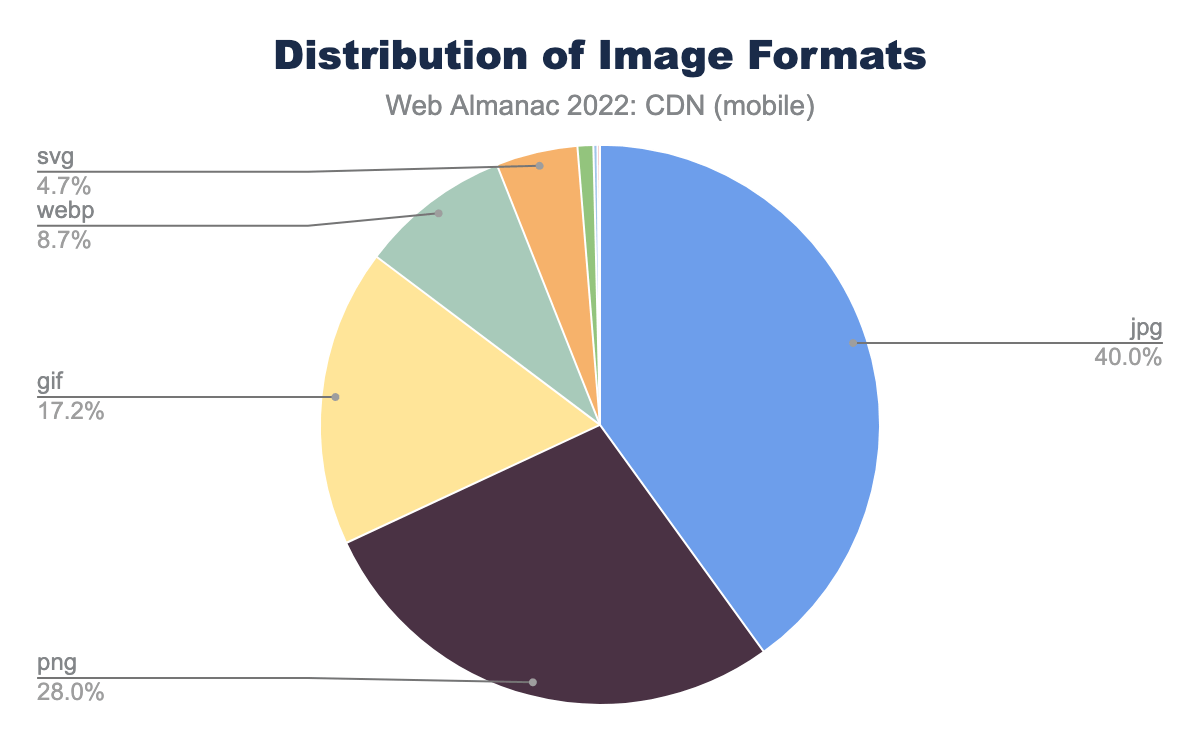

Image format adoption

CDNs have traditionally been used to cache, compress and deliver static content such as images since their inception. Since then many CDNs have added the ability to dynamically change images in both format and sizing on the fly to optimize the image for different use cases.

This may be performed automatically, based on the user agent or client hints, or by sending additional parameters in the query string whereby compute at the edge will interpret and modify the image in the response accordingly. This allows site operators to upload a single high resolution image and modify it on the fly for when lower quality or lower resolution images are needed such as in thumbnails.

Across both desktop and mobile the dominant image formats were JPG (JPEG) and PNG. JPG provides a lossly compressed file format optimizing for size. PNG or Portable Graphics Format supports lossless compression meaning no data will be lost when the image is compressed, however the image overall is larger in size than a JPG. For more information on JPG vs PNG visit Adobe’s website.

Conclusion

From our continued study in the past years, we can see that the CDNs have not only been vital to website owners in order to reliably deliver content from origin to any user across the globe, they have also played a major role in new security and web standards adoption.

In general, we have seen the rise in the usage of CDNs across the board. We saw that the CDN greatly facilitated the adoption new web security standards such as TLS 1.3 where we saw much higher percentage of traffic using TLS 1.3 came from CDN.

When it comes to the adoption of new web standards and new web technologies such as HTTP/2, Brotli compression we again saw CDNs leading the way. Much higher percentages of websites served out of CDN saw these new standards being adopted. From the end-user perspective this is very positive development as they will be able use the site securely while getting the optimal user experience.

We are also looking at new metrics like Client Hints and image format adoption starting this year. We will be able to get more insights as we collect more data for the next year.

There are limitations to the insights we can deduce about CDNs from the outside, since it is hard to know the secret sauce powering them behind the scenes. However, we have crawled the domains and compared the ones on CDNs against those who are not. We can see that CDNs have been an enabler for websites to adopt new web protocols, from the network layer to the application layer.

This role of CDNs is highly valuable and this will continue to be the case. CDN providers are also a key part of the Internet Engineering Task Force, where they help shape the future of the internet. They will continue to play a key role aiding internet-enabled industries to operate smoothly, reliably and quickly.

We look forward to the next year to collect more data and provide useful insights to our readers.