Security

Introduction

In many ways, 2020 has been an extraordinary year. As a result of the global pandemic, our day-to-day lives have changed drastically. Instead of meeting in person with friends and family, many have to rely on social media to keep in touch. This has led to a significant increase in traffic volumes for many different applications, as a result of the increased amount of time that users spend online. This also means that security has never been more important to ensure that the information we share online on various platforms remains secure.

Many of the platforms and services that we use on a daily basis strongly rely on web resources, ranging from cloud-based APIs, microservices, and most importantly, web applications. Keeping these systems secure is a non-trivial task. Fortunately, throughout the past decade, web security research has been continuously advancing. On the one hand researchers are discovering new types of attacks and sharing the results with the wider community to raise awareness. On the other hand, many engineers and developers have been tirelessly working to provide website operators with the right set of tools and mechanisms that can be used to prevent or minimize the consequences of attacks.

In this chapter, we explore the current state-of-practice for security on the Web. By analyzing the adoption of various security features in depth and at a large scale we gather insights on the different ways that website owners apply these security mechanisms, driven by the incentive to protect their users.

We not only look at the adoption of security mechanisms in individual websites. We analyze how different factors, such as the technology stack that is used to build a website, affect the prevalence of security headers, and thus improve overall security. Furthermore, it is safe to say that ensuring a website is secure requires a holistic approach covering many different facets. Therefore we also evaluate other aspects, such as the patching practices for various widely used web technologies.

Methodology

Throughout this chapter, we report on the adoption of various security mechanisms on the web. This analysis is based on data that was collected for the home page of 5.6 million desktop domains and 6.3 million mobile domains. Unless explicitly stated otherwise, the reported numbers are based on the mobile dataset, as it is larger in size. Because most websites are included in both datasets, the resulting measurements are mostly similar. Any significant difference between the two datasets are reported throughout the text or is apparent from the figures. For more information on how the data has been collected, please refer to the Methodology.

Transport security

The last year has seen a continuation of the growth of HTTPS on websites. Securing the transport layer is one of the most core parts of web security–unless you can be confident the resources downloaded for a website have not been altered in transit, and that you are transporting data to and from the website you think you are, any certainties about the website security are effectively rendered null and void.

Moving our web traffic to HTTPS, and eventually marking HTTP as non-secure is being driven by web browsers restricting powerful new features to the secure context (the carrot) while also increasing warnings shown to users when unencrypted connections are used (the stick).

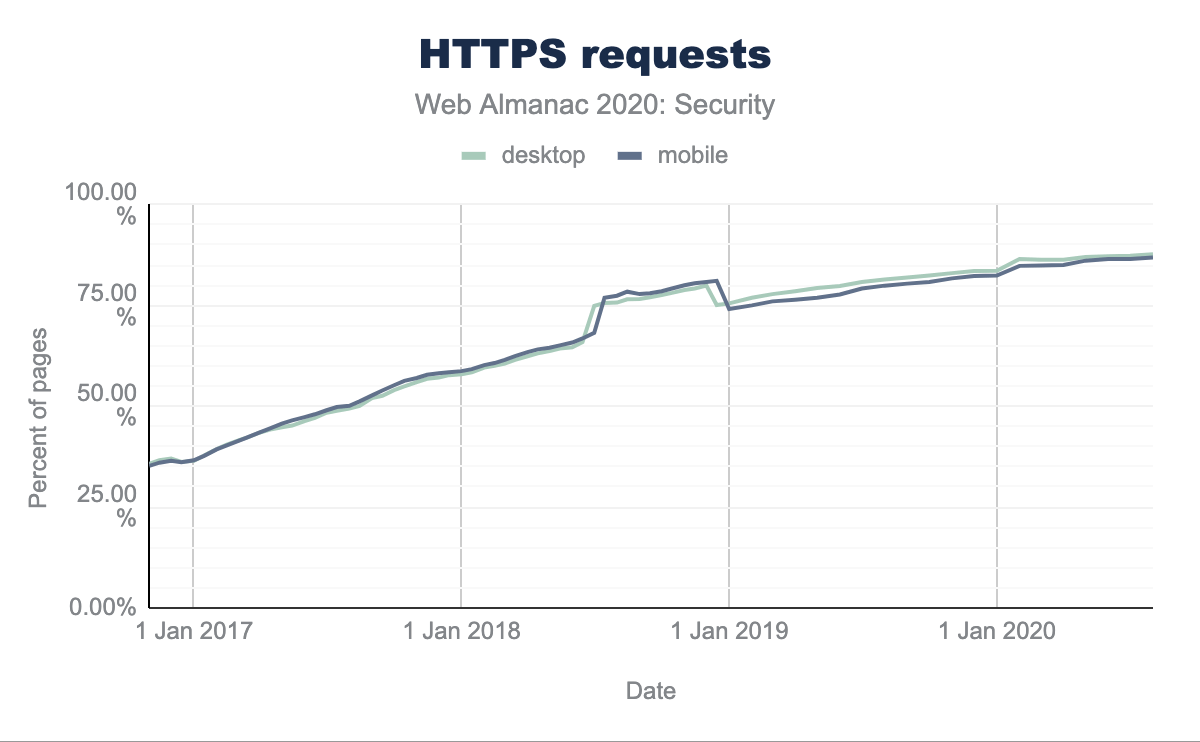

The effort is paying off and we are now seeing 87.70% of requests on desktop and 86.90% of requests on mobile being served over HTTPS.

(Source: HTTP Archive)

One slight concern as we reach the end of this goal, is a noticeable “leveling off” of the impressive growth of the last few years. Unfortunately the long tail of the internet means older legacy sites are not maintained and may never be run over HTTPS, meaning they will eventually become inaccessible to most users.

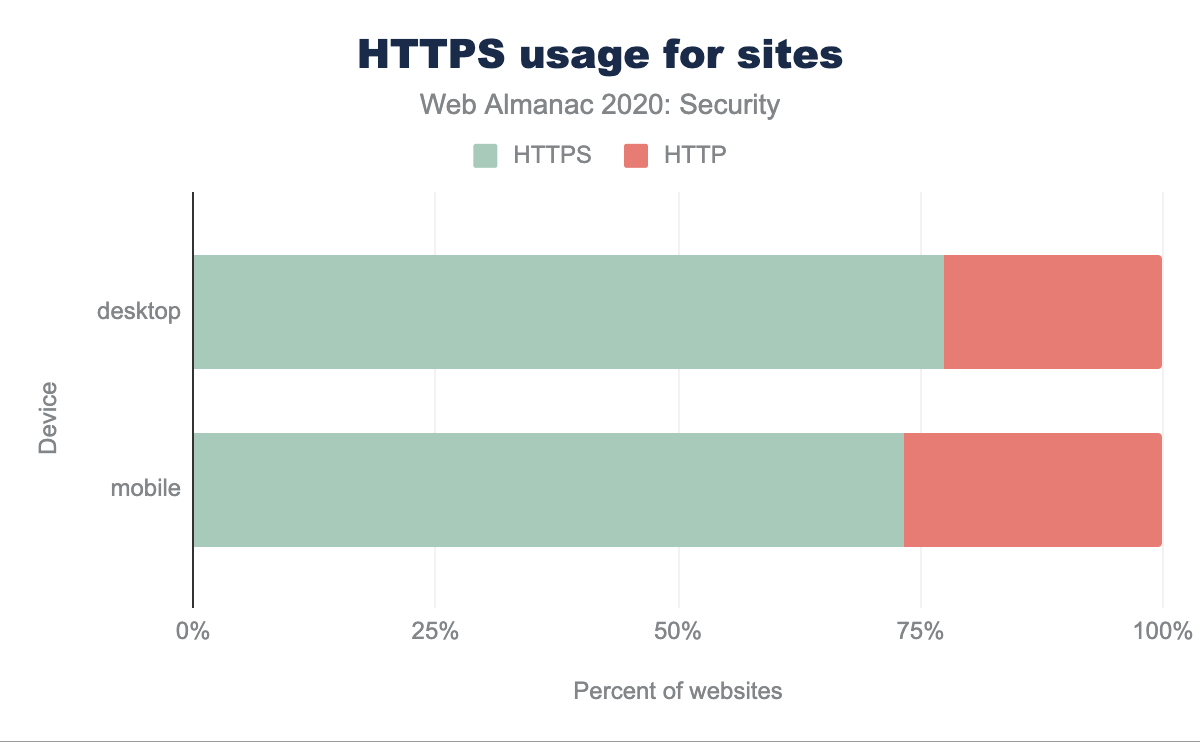

Whilst the high volume of requests is encouraging, these can often be dominated by third-party requests and services like Google Analytics, fonts or advertisements. Websites themselves can lag, but again we see encouraging use with between 73% and 77% of sites now being served over HTTPS.

Protocol versions

As HTTPS is now well and truly the norm, the challenge moves from having any sort of HTTPS, to ensuring that secure versions of the underlying TLS (Transport Layer Security) protocol are being used. TLS needs maintenance as versions become older, vulnerabilities are found and compute power increases making attacks more achievable.

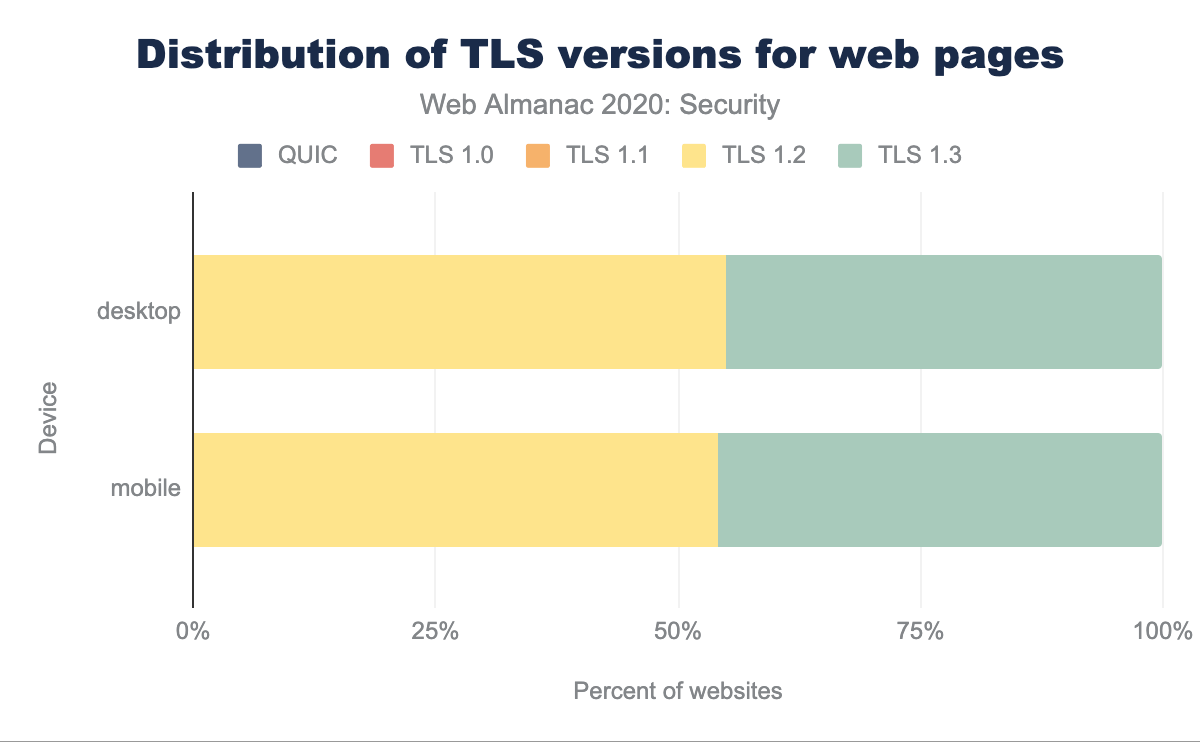

TLSv1.0 usage is already basically zero and whilst it may seem encouraging that the public web has embraced more secure protocols so definitively, it should be noted that all mainstream browsers—including Chrome that our crawl is based upon—block this by default which goes a large way to explaining this.

These figures are a slight improvement on last year’s protocol analysis with an approximately 5% increase in TLSv1.3 usage, and the corresponding drop in TLSv1.2. That seems a small increase and it would seem like the high usage of the relatively new TLSv1.3 noted last year was likely due to the initial support from large CDNs. Therefore making more significant progress in TLSv1.3 adoption will likely take a long time as those still using TLSv1.2 are potentially managing this themselves or with a hosting provider that does not yet support this.

Cipher suites

Within TLS there are a number of cipher suites that can be used with varying levels of security. The best ciphers support forward secrecy key exchange, meaning even if the server’s keys are compromised, old traffic that used those keys cannot be decrypted.

In the past, newer versions of TLS added support for newer ciphers but rarely removed older versions. This is one of the reasons TLSv1.3 is more secure as it does a large clear down of older ciphers currently. The popular OpenSSL library only supports five secure ciphers in this version–all of which support forward secrecy. This prevents downgrade attacks where a less secure cipher is forced to be used.

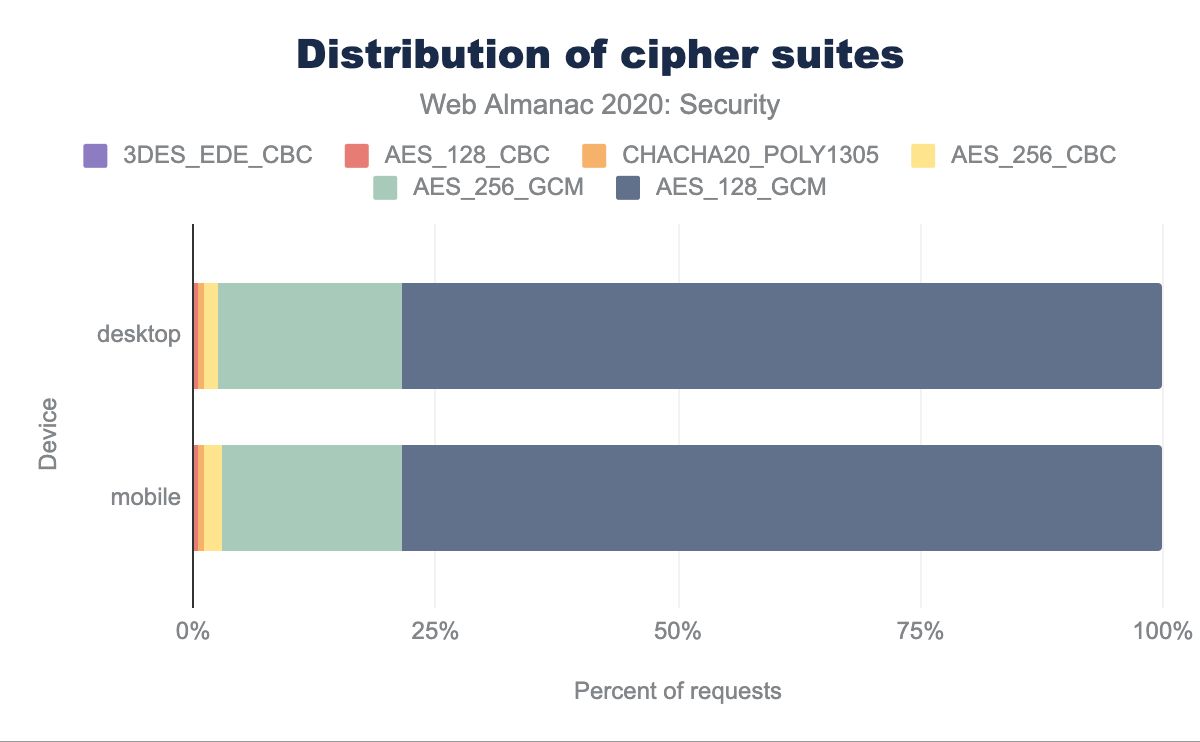

All sites really should be using forward secrecy ciphers and it is good to see 98.14% of desktop sites and 98.03% of mobile sites using ciphers with forward secrecy.

Assuming forward secrecy is a given, the main choice in selecting a cipher is between the level of encryption—higher key sizes will take longer to break, but at the cost of more compute intensive to encrypt and decrypt the connection, particularly for initial connection. For the block cipher mode GCM should be used and CBC is considered weak due to padding attacks.

For the widely used Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) key sizes of 128-bit and 256-bit encryption are common. 128-bit is still sufficient for most sites, though 256-bit would be preferred.

We can see from the above chart that AES_128_GCM is the most common and is used by 78.4% of desktop and mobile sites. AES_256_GCM is used by 19.1% of desktop and 18.5% of mobile sites with the other sites likely being the ones on older protocols and cipher suites.

One important point to note is that our data is based on running Chrome to connect to a site, and it will use a single protocol cipher to connect. Our methodology does not allow us to see the full range of protocols and cipher suites supported, and only the one that was actually used for that connection. For that information we would need to look at other sources like SSL Pulse from SSL Labs, but with most modern browsers now supporting similar TLS capabilities the above data is what we would expect the vast majority of users to use.

Certificate Authorities

Next we will look at the Certificate Authorities (CAs) issuing the TLS certificates used by the sites we have crawled. Last year’s chapter, looked at the requests for this data, but that will be dominated by popular third parties like Google (who also dominate again this year from that metric), so this year we are going to present the CAs used by the websites themselves, rather than all the other requests they load.

| Issuer | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| Let’s Encrypt Authority X3 | 44.65% | 46.42% |

| Cloudflare Inc ECC CA-3 | 8.49% | 8.69% |

| Sectigo RSA Domain Validation Secure Server CA | 8.27% | 7.91% |

| cPanel, Inc. Certification Authority | 4.71% | 5.06% |

| Go Daddy Secure Certificate Authority - G2 | 4.30% | 3.66% |

| Amazon | 3.12% | 2.85% |

| DigiCert SHA2 Secure Server CA | 2.04% | 1.78% |

| RapidSSL RSA CA 2018 | 2.01% | 1.96% |

| Cloudflare Inc ECC CA-2 | 1.95% | 1.70% |

| AlphaSSL CA - SHA256 - G2 | 1.35% | 1.30% |

It is no surprise to see Let’s Encrypt well in the lead easily taking the top spot; its combination of free and automated certificates is proving a winner with both individual website owners and platforms. Cloudflare similarly offers free certificates for its customers taking the number two and number nine position. What is more interesting there is that it is the ECC Cloudflare issuer that is being used. ECC certificates are smaller and so more efficient than RSA certificates but can be complicated to deploy as support is not universal and managing both certificates often requires extra effort. This is the benefit of a CDN or hosted provider if they can manage this for you like Cloudflare does here. Browsers that support ECC (like the Chrome browser we use in our crawl) will use that, and older browsers will use RSA.

Browser enforcement

Although having a secure TLS configuration is paramount to defend against cryptographic attacks, additional protections are still needed to protect web users from adversaries on the network. For instance, as soon as the user loads any website over HTTP, an attacker can inject malicious content to, for instance, make requests to other sites.

Even when sites are using the strongest ciphers and latest protocols, an adversary can still use SSL stripping attacks to trick the victim’s browser into believing that the connection is over HTTP instead of HTTPS. Moreover, without adequate protections in place, a user’s cookies can be attached in the initial plaintext HTTP request, allowing the attacker to capture them on the network.

To overcome these issues, browsers have provided additional features that can be enabled to prevent this.

HTTP Strict Transport Security

The first one is HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS), which can easily be enabled by setting a response header consisting of several attributes. For this header we find an adoption rate of 16.88% within the mobile home pages. Of the sites that enable HSTS, 92.82% do so successfully. That is, the max-age attribute (which determines how many seconds the browser should only visit the website over HTTPS) has a value larger than 0.

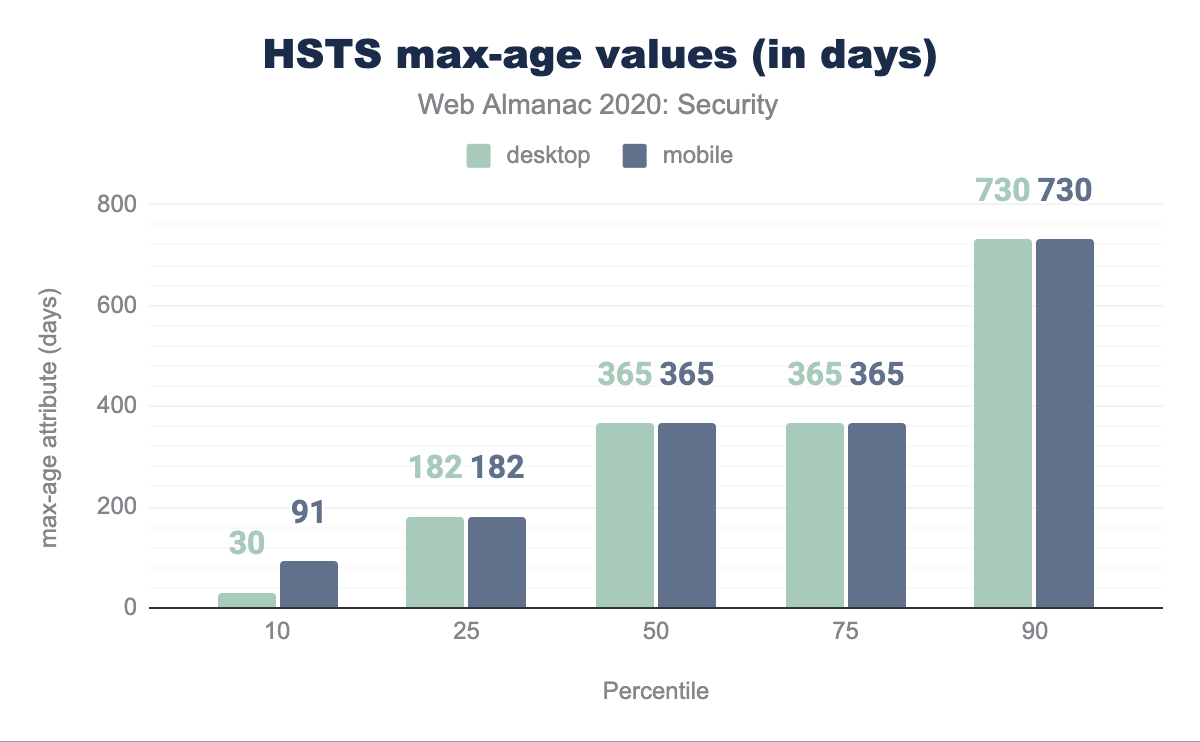

max-age attribute, converted to days. In the 10th percentile desktop is 30 days and mobile is 91, in the 25th percentile both are 182 days, in the 50th percentile both are 365 days, the 75th percentile is the same at 365 days for both and the 90th percentile has 730 days for both.max-age values (in days).

Looking at the different values for this attribute, we can clearly see that the majority of websites are confident that they will be running over HTTPS in the considerable future: more than half request the browser to use HTTPS for at least 1 year.

One website might have been a bit too enthusiastic about how long their site will be available over HTTPS and set a max-age attribute value that translates to 1,000,000,000,000,000 years. Ironically, some browsers do not handle such a large value well, and actually disable HSTS for that site!

| HSTS Directive | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

Valid max-age |

92.21% | 92.82% |

includeSubdomains |

32.97% | 32.14% |

preload |

16.02% | 16.56% |

It is encouraging to see that the adoption of the other attributes is growing compared to last year: includeSubdomains is now at 32.14% and preload at 16.56% of HSTS policies.

Cookies

From a security point of view, the automatic inclusion of cookies in cross-site requests can be seen as the main culprit of several classes of vulnerabilities. If a website does not have the adequate protections is place (e.g. requiring a unique token on state-changing requests), they may be susceptible to Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) attacks. As an example, an attacker may issue a POST request in the background, without the user being aware to, for instance, change the password of an unwitting visitor. If the user is logged in, the browser would normally automatically include the cookies in such a request.

Several other types of attacks rely on the inclusion of cookies in cross-site requests, such as Cross-Site Script Inclusion (XSSI) and various techniques in the XS-Leaks vulnerability class. Furthermore, because the authentication of users is often only done through cookies, an attacker could impersonate a user by obtaining their cookies. This could be done in a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack, tricking the user to make an authenticated over an insecure channel. Alternatively, by exploiting a cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability, the attacker could leak the cookies by accessing document.cookie through the DOM.

To defend against the threats posed by cookies, website developers can make use of three attributes that can be set on cookies: HttpOnly, Secure and SameSite. The first prevents the cookie from being accessed from JavaScript, preventing an adversary from stealing them in an XSS attack. Cookies that have the Secure attribute set will only be sent over a secure HTTPS connection, preventing them to be stolen in a MITM attack.

The attribute that was introduced most recently, SameSite, can be used to restrict how cookies are sent in a cross-site context. The attribute has three possible values: None, Lax, and Strict. Cookies with SameSite=None will be sent in all cross-site requests, whereas cookies with the attribute set to Lax will only be sent in navigational requests, e.g. when the user clicks a link and navigates to a new page. Finally, cookies with the SameSite=Strict attribute will only be sent in a first-party context.

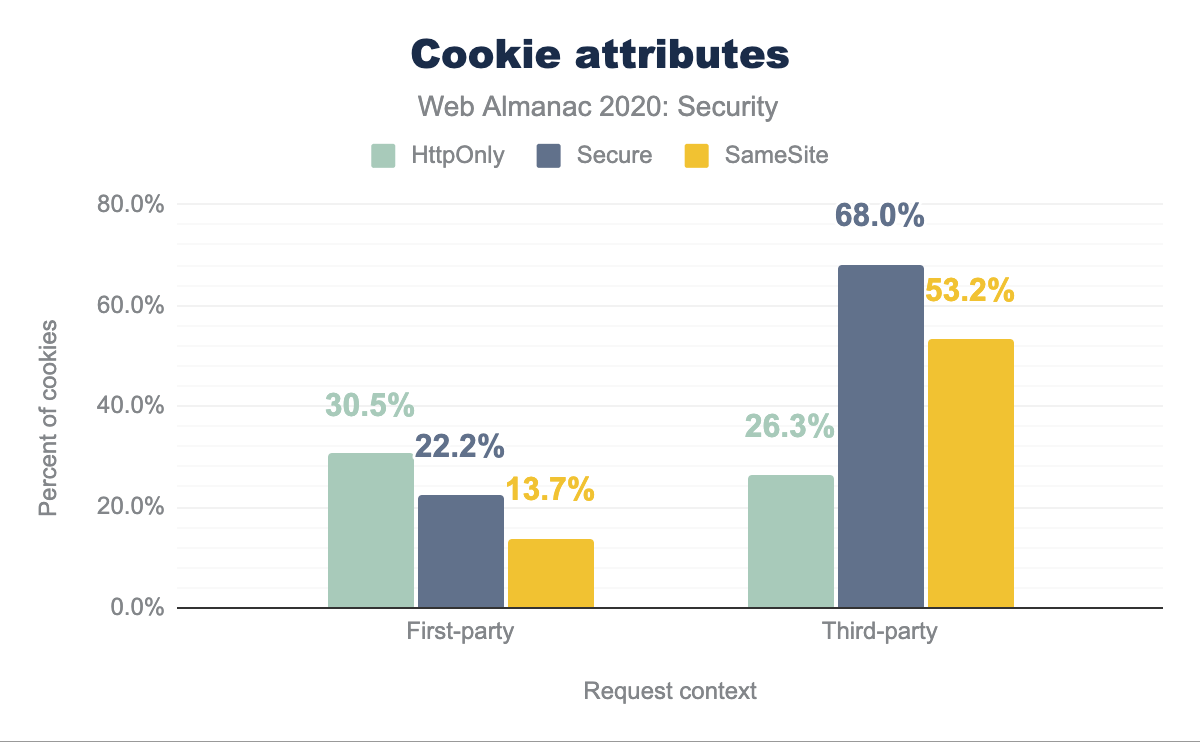

HttpOnly is used by 30.5%, Secure by 22.2%, and SameSite by 13.7%, while for third-party HttpOnly is used by 26.3%, Secure by 68.0%, and SameSite by 53.2%.Our results, which are based on 25 million first-site cookies and 115 million third-party cookies, shows that the usage of the cookie attributes strongly depends on the context in which they are set. We can observe a similar usage of the HttpOnly attribute on cookies for both first-party (30.5%) and third-party (26.3%) cookies.

However, for the Secure and SameSite attributes we see a significant difference: The Secure attribute is present on 22.2% of all cookies set in a first-party context, whereas 68.0% of all cookies set by third-party requests on mobile home pages have this cookie attribute. Interestingly, for desktop pages, only 35.2% of the third-party cookies had the attribute.

For the SameSite attribute, we can see a significant increase in their usage, compared to last year, when only 0.1% of the cookies had this attribute. As of August 2020, we observed that 13.7% of the first-party cookies and 53.2% of third-party cookies have the SameSite attribute set.

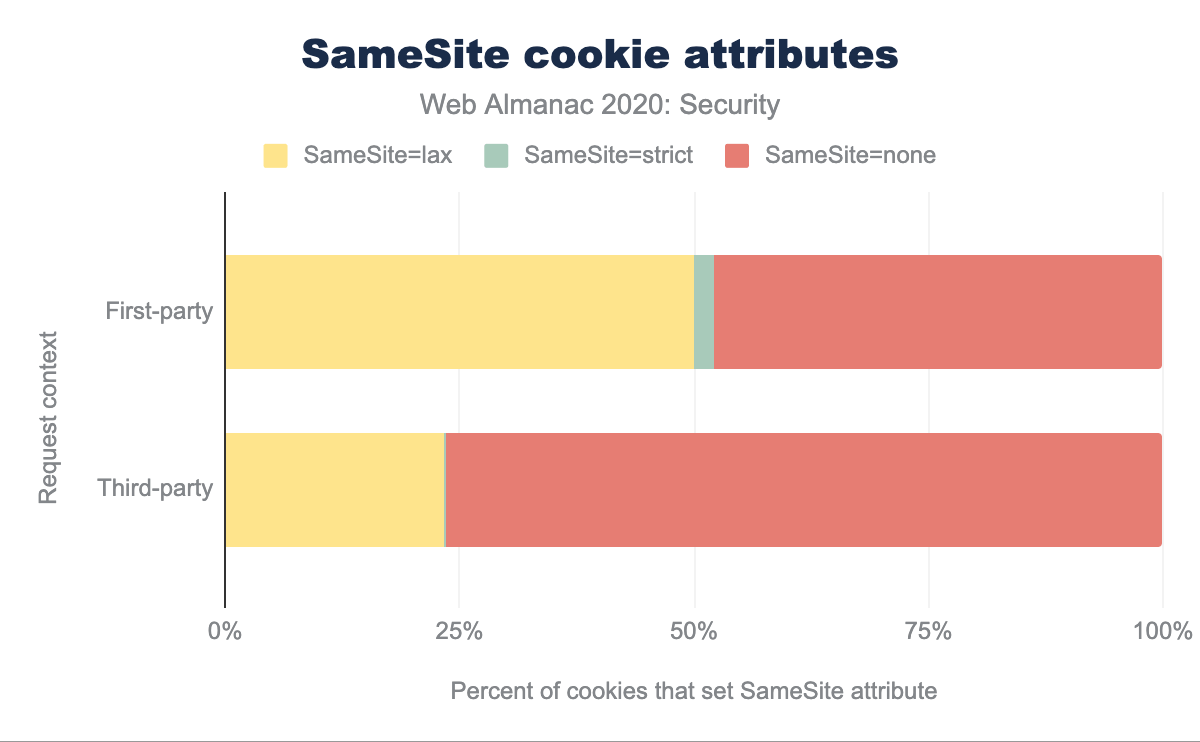

Presumably, this significant change in adoption is related to the decision of Chrome to make SameSite=Lax the default option. This is confirmed by looking more closely at the values set in the SameSite attribute: the majority of third-party cookies (76.5%) have the attribute value set to None. For first-party cookies, the share is lower, at 48.0%, but still significant. It’s important to note that because the crawler does not log in to websites, the cookies used to authenticate users may be different.

SameSite=lax is used by 50.06%, SameSite=strict by 2.03%, and SameSite=none by 47.96%, while for third-party SameSite=lax is used by 23.40%, SameSite=strict by 0.10%, and SameSite=none by 76.50%.One additional mechanism that can be used to protect cookies is to prefix the name of the cookie with __Secure- or __Host-. Cookies with any of these two prefixes will only be stored in the browser if they have the Secure attribute set. The latter imposes an additional restriction, requiring the Path attribute to be set to / and preventing the use of the Domain attribute. This prevents attackers from overriding the cookie with other values, in an attempt to perform a session fixation attack.

The usage of these prefixes is relatively small: in total we found 4,433 (0.02%) first-party cookies that were set with the __Secure- prefix and 1,502 (0.01%) with the __Host- prefix. For cookies set in a third-party context, the relative number of prefixed cookies is similar.

Content inclusion

Modern web applications include a large variety of third-party components, ranging from JavaScript libraries, to video players, to external plugins. From a security perspective, including potentially untrusted content in your web page may pose various threats, such as cross-site scripting if malicious JavaScript gets included. To defend against these threats, browsers have several mechanisms that can be used to limit which sources content can be included from, or to impose limitations on the included content.

Content Security Policy

One of the predominant mechanisms to indicate to the browser which origins are allowed to load content, is the Content-Security-Policy (CSP) response header. Through numerous directives, a website administrator can have fine-grained control over how content can be included. For instance, the script-src directive indicates from which origins scripts can be loaded. Overall, we found that a CSP header was present on 7.23% of all pages which, while still small, is a notable increase of 53% from last year, when CSP adoption was at 4.73% for mobile pages.

| Directive | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

upgrade-insecure-requests |

61.61% | 61.00% |

frame-ancestors |

55.64% | 56.92% |

block-all-mixed-content |

34.19% | 35.61% |

default-src |

18.51% | 16.12% |

script-src |

16.99% | 16.63% |

style-src |

14.17% | 11.94% |

img-src |

11.85% | 10.33% |

font-src |

9.75% | 8.40% |

Interestingly, when we look at the most commonly used directives in CSP policies, the most common directive is upgrade-insecure-requests, which is used to signal to the browser that any content that is included from an insecure scheme should instead be accessed via a secure HTTPS connection to the same host.

For instance, <img src="http://example.com/foo.png"> would normally have the image fetched over an insecure connection but when the upgrade-insecure-requests directive is present, it will automatically be fetched over HTTPS (https://example.com/foo.png).

This is particularly helpful as browsers block mixed content: for pages that are loaded over HTTPS, content that is included from HTTP would be blocked without the upgrade-insecure-requests directive. The adoption of this directive is likely much higher relative to the others as it is a good starting point for a Content Security Policy as it is unlikely to break content and is easy to implement.

The CSP directives that indicate from which sources content can be included (the *-src directives), have a much lower adoption: only 18.51% of the CSP policies served on desktop pages and 16.12% on mobile pages. One of the reasons for this, is that web developers are facing many challenges in the adoption of CSP. Although a strict CSP policy can provide significant security benefits well beyond thwarting XSS attacks, an ill-defined one may prevent certain valid content from loading.

To allow web developers to evaluate the correctness of their CSP policy, there also exists a non-enforcing alternative, which can be enabled by defining the policy in the Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only response header. The prevalence of this header is fairly small: 0.85% of desktop and mobile pages. It should be noted however that this is often a transitionary header and so the percentage likely indicates the sites that intend to transition to using CSP and are only using the Report-Only header for a limited amount of time.

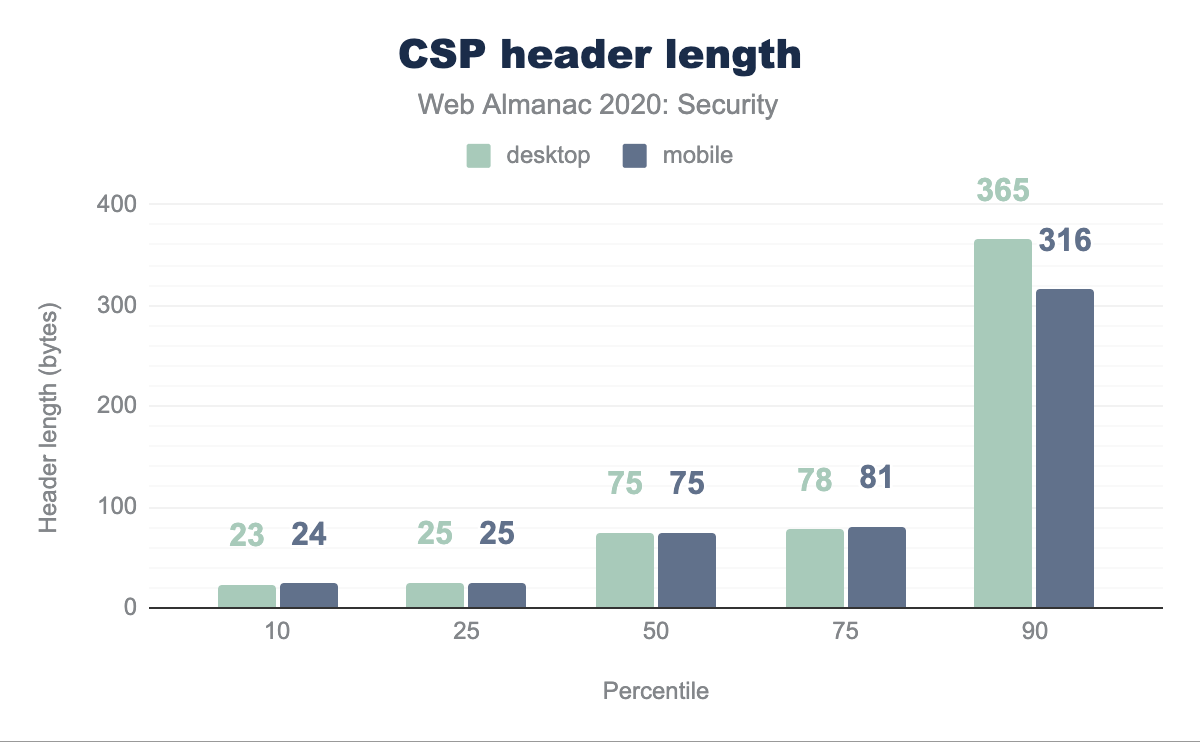

Overall, the length of the Content-Security-Policy response header is quite limited: the median length for the value of the header is 75 bytes. This is mainly due to the short single-purpose CSP policies that are frequently used. For instance, 24.64% of the policies defined on desktop pages only have the upgrade-insecure-requests directive.

The most common header value, making up for 29.44% of all policies defined on desktop pages, is block-all-mixed-content; frame-ancestors 'none'; upgrade-insecure-requests;. This policy will prevent the page from being framed, tries to upgrade requests to the secure protocol, and blocks the content if that fails.

On the other side of the spectrum, the longest CSP policy that we observed was 22,333 bytes long.

| Origin | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| https://www.google-analytics.com | 1.50% | 1.46% |

| https://www.googletagmanager.com | 1.04% | 1.07% |

| https://fonts.googleapis.com | 0.99% | 0.99% |

| https://www.youtube.com | 1.02% | 0.91% |

| https://fonts.gstatic.com | 0.95% | 0.95% |

| https://www.google.com | 0.95% | 0.94% |

| https://connect.facebook.net | 0.89% | 0.83% |

| https://stats.g.doubleclick.net | 0.72% | 0.70% |

| https://www.facebook.com | 0.66% | 0.65% |

| https://www.gstatic.com | 0.54% | 0.57% |

The external origins from which content is allowed to be loaded is, not unexpectedly, in line with the origins from which third-party content is most frequently included. The 10 most common origins defined in the *-src attributes in CSP policies can all be linked to Google (analytics, fonts, ads), and Facebook.

One site went above and beyond to ensure that all of their included content would be allowed by CSP and allowed 403 different hosts in their policy. Of course this makes the security benefit marginal at best, as certain hosts might allow for CSP bypasses, such as a JSONP endpoint that allows calling arbitrary functions.

Subresource integrity

Many JavaScript libraries and stylesheets are included from CDNs. As a result, if the CDN is compromised, or attackers would find another way to replace the often-included libraries, this could have disastrous consequences.

To limit the consequences of a compromised CDN, web developers can use the subresource integrity (SRI) mechanism. An integrity attribute, which consists of the hash of the expected contents, can be defined On <script> and <link> elements. The browser will compare the hash of the fetched script or stylesheet with the hash defined in the attribute, and only load its contents if there is a match.

The hash can be computed with three different algorithms: SHA256, SHA384, and SHA512. The first two are most frequently used: 50.90% and 45.92% respectively for mobile pages (usage is similar on desktop pages). Currently, all three hashing algorithms are considered safe to use.

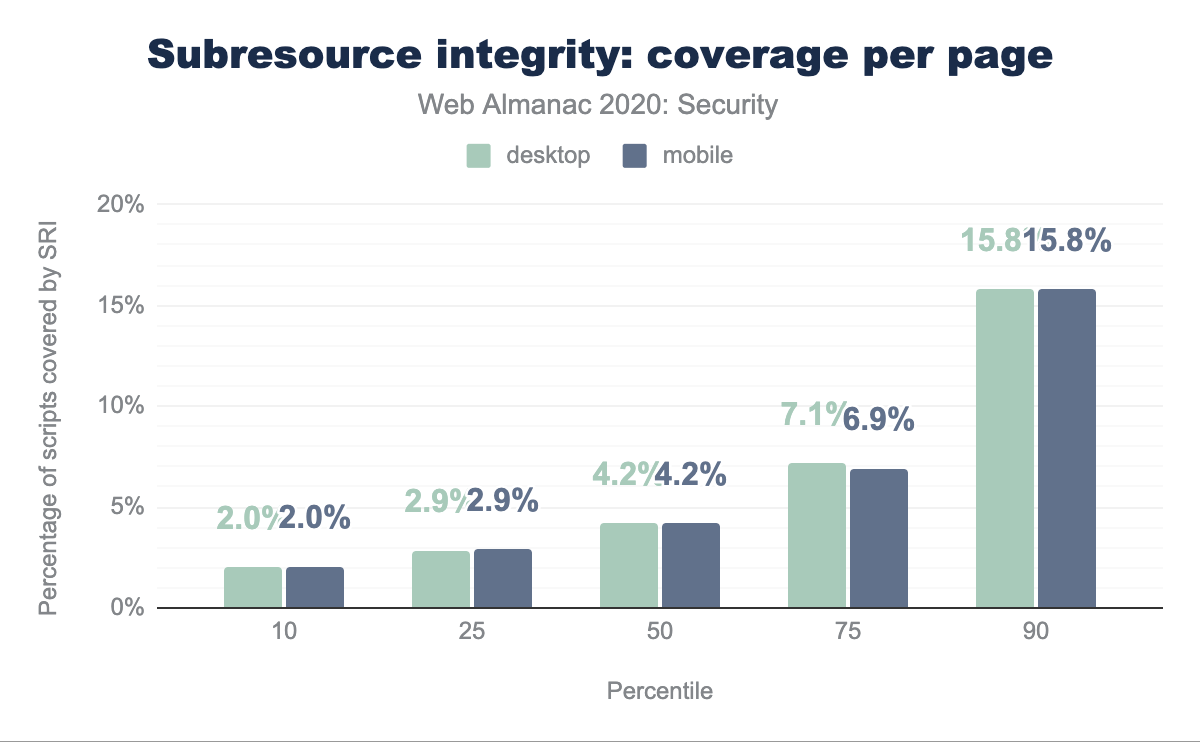

On 7.79% of the desktop pages, at least one element contained the integrity attribute and for mobile pages this is 7.24%. The attribute is mainly used on <script> elements: 72.77% of all the elements with the integrity attribute, were on script elements.

When looking more closely at the pages that have at least one script protected with SRI, we find that the majority of scripts on these pages do not have the integrity attribute. Less than 1 out of 20 scripts were protected with SRI on most sites.

| Host | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| cdn.shopify.com | 44.95% | 45.72% |

| code.jquery.com | 14.05% | 13.38% |

| cdnjs.cloudflare.com | 11.45% | 10.47% |

| maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com | 5.03% | 4.76% |

| stackpath.bootstrapcdn.com | 4.96% | 4.74% |

Looking at the most popular hosts from which SRI-protected scripts are included, we can see some driving forces that push the adoption. For instance, almost half of all the scripts that are protected with subresource integrity originate from cdn.shopify.com, most likely because the Shopify SaaS enables it by default for their customers.

The rest of the top 5 hosts from which SRI-protected scripts are included is made up of three CDNs: jQuery, cdnjs, and Bootstrap. It is probably not coincidental that all three of these CDNs have the integrity attribute in the example HTML code.

Feature policy

Browsers provide a myriad of APIs and functionalities, some of which might be detrimental to the user experience or privacy. Through the Feature-Policy response header, websites can indicate which features they want to use, or perhaps more importantly, which they do not want to use.

In a similar fashion, by defining the allow attribute on <iframe> elements, it is also possible to determine which features the embedded frames are allowed to use. For instance, via the autoplay directive, websites can indicate whether they want videos in frames to automatically start playing when the page is loaded.

| Directive | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

encrypted-media |

78.83% | 78.06% |

autoplay |

47.14% | 48.02% |

picture-in-picture |

23.12% | 23.28% |

accelerometer |

23.10% | 23.22% |

gyroscope |

23.05% | 23.20% |

microphone |

8.57% | 8.70% |

camera |

8.48% | 8.62% |

geolocation |

8.09% | 8.40% |

vr |

7.74% | 8.02% |

fullscreen |

4.85% | 4.82% |

sync-xhr |

0.00% | 0.21% |

The Feature-Policy response header has a fairly low adoption rate, at 0.60% of the desktop pages and 0.51% of mobile pages. On the other hand, Feature Policy was enabled on 11.8% of the 13.2 million frames that were found on the desktop pages. On mobile pages, 10.8% of the 13.9 million frames contained the allow attribute.

Based on the most commonly used directives in the Feature Policy on iframes, we can see that these are mainly used to control how the frames play videos. For instance the most prevalent directive, encrypted-media, is used to control access to the Encrypted Media Extensions API, which is required to play DRM-protected videos. The most common iframe origins with a Feature Policy were https://www.facebook.com and https://www.youtube.com (49.87% and 26.18% of the frames with a Feature Policy on desktop pages respectively).

Iframe sandbox

By including an untrusted third-party in an iframe, that third-party can try to launch a number of attacks on the page. For instance, it could navigate the top page to a phishing page, launch pop-ups with fake anti-virus advertisements, etc.

The sandbox attribute on iframes can be used to restrict the capabilities, and therefore also the opportunities for launching attacks, of the embedded web page. As embedding third-party content such as advertisements or videos is common practice on the web, it is not surprising that many of these are restricted via the sandbox attribute: 18.3% of the iframes on desktop pages have a sandbox attribute while on mobile pages this is 21.9%.

| Directive | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

allow-scripts |

99.97% | 99.98% |

allow-same-origin |

99.64% | 99.70% |

allow-popups |

83.66% | 89.41% |

allow-forms |

83.43% | 89.22% |

allow-popups-to-escape-sandbox |

81.99% | 87.22% |

allow-top-navigation-by-user-activation |

59.64% | 69.45% |

allow-pointer-lock |

58.14% | 67.65% |

allow-top-navigation |

21.38% | 17.31% |

allow-modals |

20.95% | 17.07% |

allow-presentation |

0.33% | 0.31% |

When the sandbox attribute of an iframe has an empty value, this results in the most restrictive policy: the embedded page cannot execute any JavaScript code, no forms can be submitted and no popups can be created, to name a few restrictions.

This default policy can be relaxed in a fine-grained manner by means of different directives. The most commonly used directive, allow-scripts, which is present in 99.97% of all sandbox policies on desktop pages, allows the embedded page to execute JavaScript code. The other directive that is present on virtually all sandbox policies, allow-same-origin, allows the embedded page to retain its origin, and, for example, access cookies that were set on that origin.

Interestingly, although Feature Policy and iframe sandbox both have a fairly high adoption rate, they rarely occur simultaneously: only 0.04% of the iframes have both the allow and sandbox attribute. Presumably, this is because the iframe is created by a third-party script. A Feature Policy is predominantly added on iframes that contain third-party videos, whereas the sandbox attribute is mainly used to limit the capabilities of advertisements: 56.40% of the iframes on desktop pages with a sandbox attribute originate from https://googleads.g.doubleclick.net.

Thwarting attacks

Modern web applications are faced with a large variety of security threats. For instance, improperly encoding or sanitizing user input may result in a cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability, a class of issues that has pestered web developers for well over a decade. As web applications become more and more complex, and novel types of attacks are being discovered, even more threats are looming. XS-Leaks, for instance is a novel class of attacks that aims to leverage the user-specific dynamic responses that web applications return.

As an example, if a webmail client provides a search functionality, an attacker can trigger requests for various keywords, and subsequently try to determine, through various side-channels, whether any of these keywords yielded any results. This effectively provides the attacker with a search capability in the mailbox of an unwitting visitor on the attacker’s website.

Fortunately, web browsers also provide a large set of security mechanisms that are highly effective against limiting the consequences of a potential attack, e.g. via the script-src directive of CSP an XSS vulnerability may become very difficult or impossible to exploit.

Some other security mechanisms are even required to prevent certain types of attacks: to prevent clickjacking attacks, either the X-Frame-Options header should be present, or alternatively the frame-ancestors directive of CSP can be used to indicate trusted parties that can embed the current document.

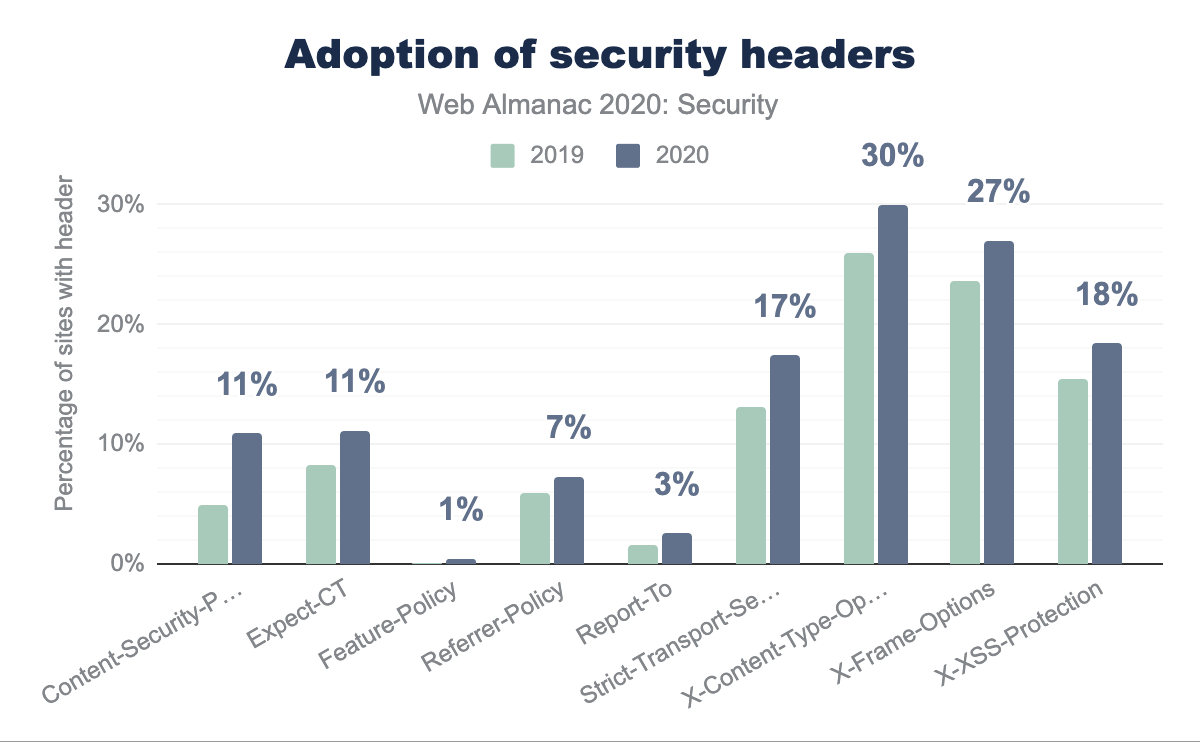

Content-Security-Policy is 5% on desktop and 11% on mobile, Expect-CT is 8% on desktop and 11% on mobile, Feature-Policy is 0% on desktop and 1% on mobile, Referrer-Policy is 6% on desktop and 7% on mobile, Report-To is 2% on desktop and 3% on mobile, Strict-Transport-Security is 13% on desktop and 17% on mobile, X-Content-Type-Options is 26% on desktop and 30% on mobile, X-Frame-Options is 24% on desktop and 27% on mobile, and X-XSS-Protection is 16% on desktop and 18% on mobile.Security mechanism adoption

The most common security response header on the Web is X-Content-Type-Options, which instructs the browser to trust the advertised content type, and thus not sniff it based on the response content. This effectively prevents MIME-type confusion attacks, for example preventing attackers from abusing a JSONP endpoint to be interpreted as HTML code in order to perform a cross-site scripting attack.

Next on the list is the X-Frame-Options (XFO) response header, which is enabled by approximately 27% of the pages. This header, along with CSP’s frame-ancestors directives are the only effective mechanisms that can be used to counter clickjacking attacks. However, XFO is not only useful against clickjacking, but also makes exploitation significantly more difficult for various other types of attacks. Although XFO is currently still the only mechanism to defend against clickjacking attacks in legacy browsers such as Internet Explorer, it is subject to double framing attacks. This issue is mitigated with the frame-ancestors CSP directive. As such, it is considered best practice to employ both headers to give users the best possible protection.

The X-XSS-Protection header, which is currently adopted by 18.39% of the websites, was used to control the browser’s built-in detection mechanism for reflected cross-site scripting. However, as of Chrome version 78, the built-in XSS detector has been deprecated and removed from the browser. This was because there exist various bypasses, and the mechanism also introduced new vulnerabilities and information leaks that could be abused by attackers. As the other browser vendors never implemented a similar mechanism, the X-XSS-Protection header effectively has no effect on modern browsers and can thus safely be removed. Nevertheless, we do see a slight increase in the adoption of this header compared to last year, from 15.50% to 18.39%.

The remainder of the top five most widely adopted headers is completed by two headers related to a website’s TLS implementation. The Strict-Transport-Security header is used to instruct the browser that the website should only be visited over an HTTPS connection for the duration defined in the max-age attribute. We explored the configuration of this header in more detail earlier in this chapter. The Expect-CT header will instruct the browser to verify that any certificate that is issued for the current website needs to appear in public Certificate Transparency logs.

Overall, we can see that the adoption of security headers has increased in the last year: the most-widely used security headers show a relative increase of 15 to 35 percent. The growth in adoption of the features that were introduced more recently, such as the Report-To and Feature-Policy headers, is also worth noting—the latter has more than tripled compared to last year. The strongest absolute growth can be seen for the CSP header, with an adoption rate growing from 4.94% to 10.93%.

Preventing XSS attacks through CSP

| Keyword | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

strict-dynamic |

2.40% | 14.68% |

nonce- |

8.72% | 17.40% |

unsafe-inline |

89.83% | 92.28% |

unsafe-eval |

84.03% | 77.48% |

Implementing a strict CSP that is useful in preventing XSS attacks is non-trivial: web developers need to be aware of all the different origins from which scripts are loaded and all inline scripts should be removed. To make adoption easier, the last version of CSP (version 3), provides new keywords that can be used in the default-src or script-src directives. For instance, the strict-dynamic keyword will allow any script that is dynamically added by an already-trusted script, e.g. when that script creates a new <script> element. From the policies that include either a default-src or script-src directive (21.17% of all CSPs), we see an adoption of 14.68% of this relatively new keyword. Interestingly, on desktop pages the adoption of this mechanism is significantly lower, at 2.40%.

Another mechanism to make adoption of CSP easier is the use of nonces: in the script-src directive of CSP, a page can enter the keyword nonce-, followed by a random string. Any script (inline or remote) that has a nonce attribute set to the same random string defined in the header will be allowed to execute. As such, through this mechanism it is not required to determine all the different origins from which scripts may be included in advance. We found that the nonce mechanism was used in 17.40% of the policies that defined a script-src or default-src directive. Again, the adoption for desktop pages was lower, at 8.72%. We have been unable to explain this large difference but would be interested in hearing any suggestions!

The two other keywords, unsafe-inline and unsafe-eval, are present on the majority of the CSPs: 97.28% and 77.79% respectively. This can be seen as a reminder of the difficulty of implementing a policy that can thwart XSS attacks. However, when the strict-dynamic keyword is present, this will effectively ignore the unsafe-inline and unsafe-eval keywords. Because the strict-dynamic keyword may not be supported by older browsers, it is considered best practice to include the two other unsafe keywords to maintain compatibility for all browser versions.

Whereas the strict-dynamic and nonce- keywords can be used to defend against reflected and persistent XSS attacks, a protected page could still be vulnerable to DOM-based XSS vulnerabilities. To defend against this class of attacks, website developers can make use of Trusted Types, a fairly new mechanism that is currently only supported by Chromium-based browsers. Despite the potential difficulties in adopting Trusted Types (websites would need to create a policy and potentially adjust their JavaScript code to comply with this policy), and given that it is a new mechanism, it is encouraging that 11 home pages already adopted Trusted Types through the require-trusted-types-for directive in CSP.

Defending against XS-Leaks with Cross-Origin Policies

To defend against the novel class of attacks called XS-Leaks, various new security mechanisms have been introduced very recently (some are still under development). Generally, these security mechanisms give website administrators more control over how other sites can interact with their site. For instance, the Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy (COOP) response header can be used to instruct browsers that the page should be process-isolated from other, potentially malicious, browser contexts. As such, an adversary would not be able to obtain a reference to the page’s global object. As a result, attacks such as frame counting are prevented with this mechanism. We found 31 early-adopters of this mechanism, which was only supported in Chrome, Edge and Firefox a few days before the data collection started.

The Cross-Origin-Resource-Policy (CORP) header, which has been supported by Chrome, Firefox and Edge only slightly longer, has already been adopted on 1,712 pages (note that CORP can/should be enabled on all resource types, not just documents, hence this number may be an underestimation). The header is used to instruct the browser how the web resource is expected to be included: same-origin, same-site, or cross-origin (going from more to less restrictive). The browser will prevent loading resources that are included in a way that is in violation with CORP. As such, sensitive resources protected with this response header are safeguarded from Spectre attacks and various XS-Leaks attacks. The Cross-Origin Read Blocking (CORB) mechanism provides a similar protection but is enabled by default in the browser (currently only in Chromium-based browsers) for “sensitive” resources.

Related to CORP is the Cross-Origin-Embedder-Policy (COEP) response header, which can be used by documents to instruct the browser that any resource loaded on the page should have a CORP header. Additionally, resources that are loaded through the Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) mechanism (e.g. through the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header) are also allowed. By enabling this header, along with COOP, the page can get access to APIs that are potentially sensitive, such as high-accuracy timers and SharedArrayBuffer, which can also be used to construct a very accurate timer. We found 6 pages that enabled COEP, although support for the header was only added to browsers a few days before the data collection.

Most of the cross-origin policies aim to disable or mitigate the potentially nefarious consequences of several browser features that have only a limited usage on the web (e.g. retaining a reference to newly opened windows). As such, enabling security features such as COOP and CORP can, in most cases, be done without breaking any functionality. Therefore it can be expected that the adoption of these cross-origin policies will significantly grow in the coming months and years.

Web Cryptography API

The Web Cryptography API offers great JavaScript functions for developers that can be used to securely run cryptographic operations on the client-side with little effort—without requiring external libraries. This JavaScript API not only provides basic cryptographic operations but can be used to generate cryptographically strong random values, hashing, signature generation and verification, encryption and decryption. With the help of this API, we can also implement algorithms for authenticating users, signing documents, protecting the confidentiality and integrity of communications securely. Consequently, this API enables more secure and data protection-compliant use-cases in the area of end-to-end encryption. This is how the Web Cryptography API makes its contribution to end-to-end encryption.

| Cryptography API | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

CryptoGetRandomValues |

70.32% | 67.94% |

SubtleCryptoGenerateKey |

0.3% | 0.2% |

SubtleCryptoEncrypt |

0.3% | 0.2% |

SubtleCryptoDigest |

0.3% | 0.3% |

CryptoAlgorithmSha256 |

0.2% | 0.2% |

Our results show that the Cypto.getRandomValues function, which allows for generating a random number (in a secure, cryptographic manner) is by far the most widely used one (desktop: 70% and mobile: 68%). We believe Google Analytic’s use of this function has a major effect on the usage measured. In general, we see that mobile websites perform slightly fewer cryptographic operations, although mobile browsers fully support this API.

Utilizing bot protection services

According to Imperva, a serious proportion (37%) of the total web traffic belongs to automated programs (so-called “bots”), and most of them are malicious (24%). Bots can be used for phishing, collecting information, exploiting vulnerabilities, DDoS, and many other purposes. Using bots is a very interesting technique for attackers and especially increases the success rate of massive attacks. That is why protecting against malicious bots can be helpful in defending against large-scale automated attacks. The following figure shows the use of third-party protection services against malicious bots.

| Service provider | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| reCAPTCHA | 8.30% | 9.03% |

| Imperva | 0.30% | 0.36% |

| hCaptcha | 0.01% | 0.01% |

| Others | <0.01% | <0.01% |

The figure above shows the use of bot protection and also the market share based on our dataset. We see that nearly 10% of desktop pages and 9% of mobile pages use such services.

Relationship between the adoption of security headers and various factors

In the previous sections we explored the adoption rate of various browser security mechanisms that need to be enabled by web pages through response headers. Next, we explore what drives websites to adopt the security features, whether it is related to country-level policies and regulations, a general interest to keep their customers safe, or whether it is driven by the technology stack that is used to build the website.

Country of a website’s visitors

There can be many different factors that affect security at the level of a country: government-motivated programs of cybersecurity may increase awareness of good security practices, a focus on security in higher education could lead to more well-informed developers, or even certain regulations might require companies and organizations to adhere to best security practices. To evaluate the differences per country, we analyze the different countries for which at least 100,000 home pages were available in our dataset, which is based on the Chrome User Experience Report (CrUX). These pages consist of those that were visited most frequently by the users in that country; as such, these also contain widely popular international websites.

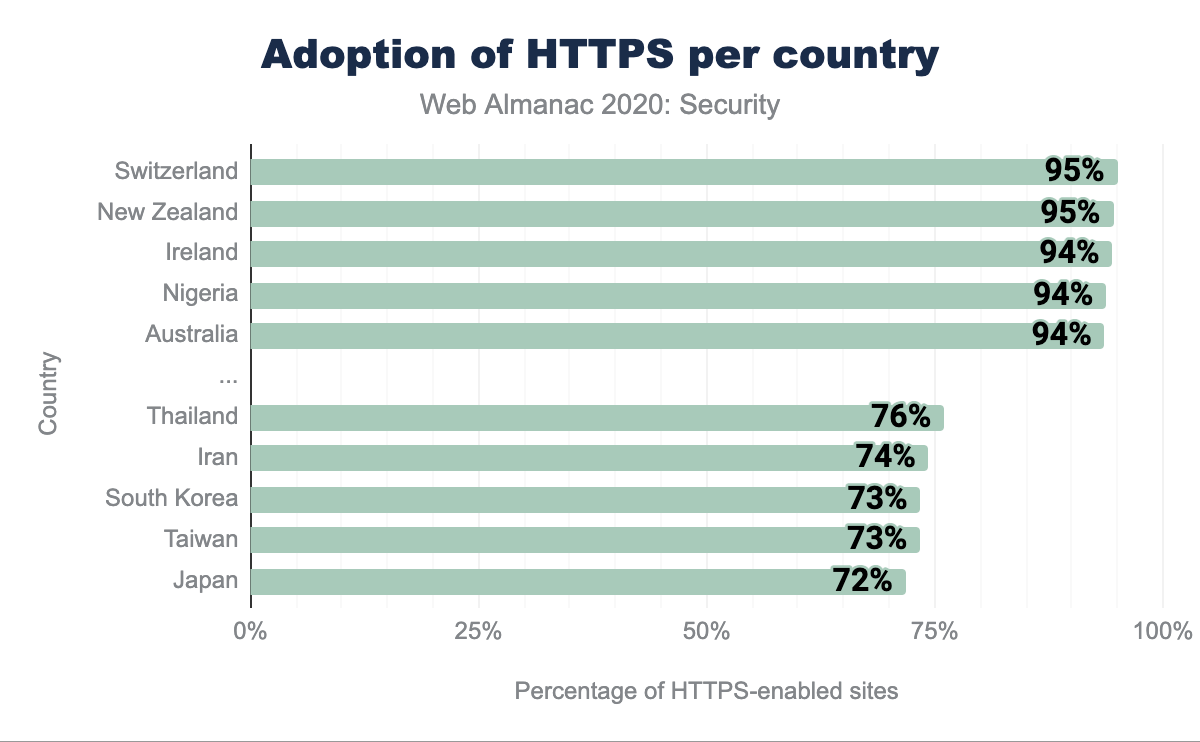

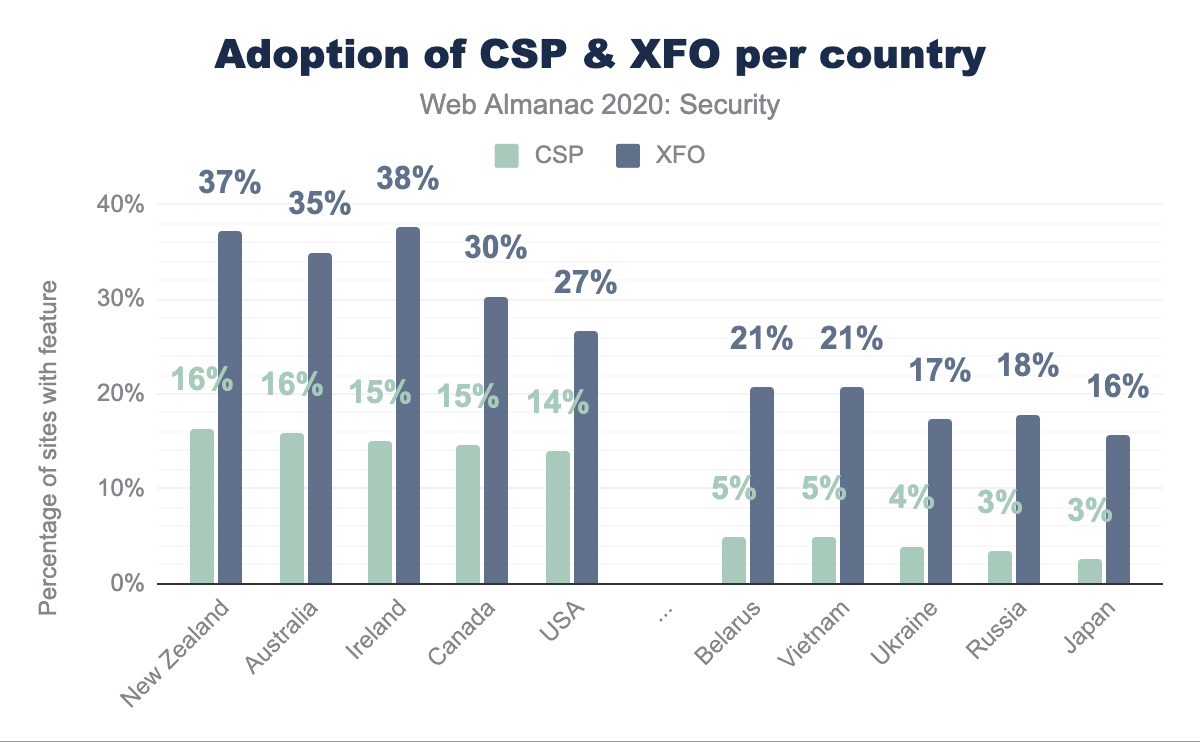

Looking at the percentage of home pages that were visited over HTTPS, we can already see a significant difference: for the top 5 best-performing countries 93-95% of the home pages were served over HTTPS. For the bottom 5, we see a much smaller adoption in HTTPS, ranging from 71% to 76%. When we look at other security mechanisms, we can see even more apparent differences between top-performing countries and countries with a low adoption rate. The top 5 countries according to the adoption rate for CSP score between 14% and 16%, whereas the bottom 5 score between 2.5% and 5%. Interestingly, the countries that perform well/poorly for one security mechanism, also do so for other mechanisms. For instance, New Zealand, Ireland and Australia consistently rank among the top 5, whereas Japan scores worst for almost every security mechanism.

Technology stack

Country-level incentives can drive the adoption of security mechanisms to a certain extent, but perhaps more important is the technology stack that website developers use when building websites. Do the frameworks easily lend themselves to enabling a certain feature, or is this a painstaking process requiring a complete overhaul of the application? Even better it would be if developers start with an already-secure environment with strong security defaults to begin with. In this section we explore different programming languages, SaaS, CMS, ecommerce and CDN technologies that have a significantly higher adoption rate for specific features (and thus can be seen as driving factors for widespread adoption). For brevity, we focus on the most widely deployed technologies, but it is important to note that many smaller technology products exist that aim to provide better security for their users.

For security features related to the transport security, we find that there are 12 technology products (mainly ecommerce platforms and CMSs) that enable the Strict-Transport-Security header on at least 90% of their customer sites. Websites powered by the top 3 (according to their market share, namely Shopify, Squarespace and Automattic), make up for 30.32% of all home pages that have enabled Strict Transport Security. Interestingly, the adoption of the Expect-CT header is mainly driven by a single technology, namely Cloudflare, which enables the header on all of their customers that have HTTPS enabled. As a result, 99.06% of the Expect-CT header presences can be related to Cloudflare.

With regard to security headers that secure content inclusion or that aim to thwart attacks, we see a similar phenomenon where a few parties enable a security header for all their customers, and thus drive its adoption. For instance, six technology products enable the Content-Security-Policy header for more than 80% of their customers. As such, the top 3 (Shopify, Sucuri and Tumblr) represent 52.53% of the home pages that have the header. Similarly, for X-Frame-Options, we see that the top 3 (Shopify, Drupal and Magento) contribute 34.96% of the global prevalence of the XFO header. This is particularly interesting for Drupal, as it is an open-source CMS that is often set up by website owners themselves. It is clear that their decision to enable X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN by default is keeping many of their users protected against clickjacking attacks: 81.81% of websites powered by Drupal have the XFO mechanism enabled.

Co-occurrence of other security headers

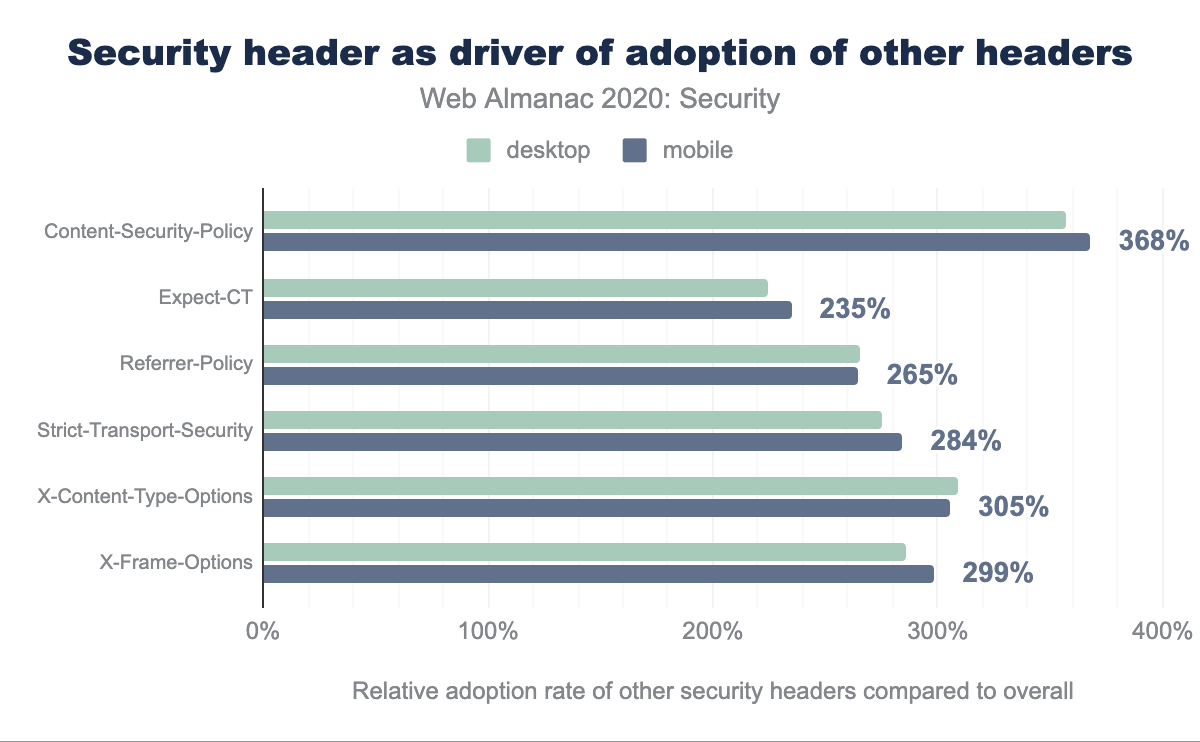

Content-Security-Policy has 357% for desktop and 368% for mobile, Expect-CT has 224% and 235% respectively, Referrer-Policy has 265% and 265%, Strict-Transport-Security has 275% and 284%, X-Content-Type-Options has 309% and 305%, and X-Frame-Options has 286% for desktop and 299% for mobile.The security “game” is highly unbalanced, and much more in the favor of attackers: an adversary only needs to find a single flaw to exploit, whereas the defender needs to prevent all possible vulnerabilities. As such, whereas adopting a single security mechanism can be very useful in defending against a particular attack, websites need multiple security features in order to defend against all possible attacks. To determine whether security headers are adopted in a one-off manner, or rather in a rigorous way to provide in-depth defenses against as many attacks as possible, we look at the co-occurrence of security headers. More precisely, we look at how the adoption of one security header affects the adoption of other headers. Interestingly, this shows that websites that adopt a single security header, are much more likely to adopt other security headers as well. For instance, for mobile home pages that contain a CSP header, the adoption of the other headers (Expect-CT, Referrer-Policy, Strict-Transport-Security, X-Content-Type-Options and X-Frame-Options) is on average 368% higher compared to the overall adoption of these headers.

In general, websites that adopt a certain security header are 2 to 3 times more likely to adopt other security headers as well. This is especially the case for CSP, which fosters the adoption of other security headers the most. This can be explained on the one hand because CSP is one of the more extensive security headers that requires considerable effort to adopt, so websites that do define a policy, are more likely to be invested in the security of their website. On the other hand, 44.31% of the CSP headers are on home pages that are powered by Shopify. This SaaS product also enables several other security headers (Strict-Transport-Security, X-Content-Type-Options and X-Frame-Options) as a default for virtually all of their customers.

Software update practices

A very large part of the Web is built with third-party components, at different layers of the technology stack. These components consist of the JavaScript libraries that are used to provide a better user experience, the Content Management Systems or web application frameworks that form the backbone of a website, and the web servers that are used to respond to requests from the visitors. Every so often a vulnerability is detected in one of these components. In the best case it is detected by a security researcher who responsibly discloses it to the affected vendor, prompting them to patch the vulnerability and release an update of their software. At this point, it is very likely that the details of the vulnerability are publicly known, and that attackers are eagerly working on creating an exploit for it. As such, it is of key importance for website owners to update the affected software as fast as possible to safeguard them from these n-day exploits. In this section we explore how well the most widely used software is kept up-to-date.

WordPress

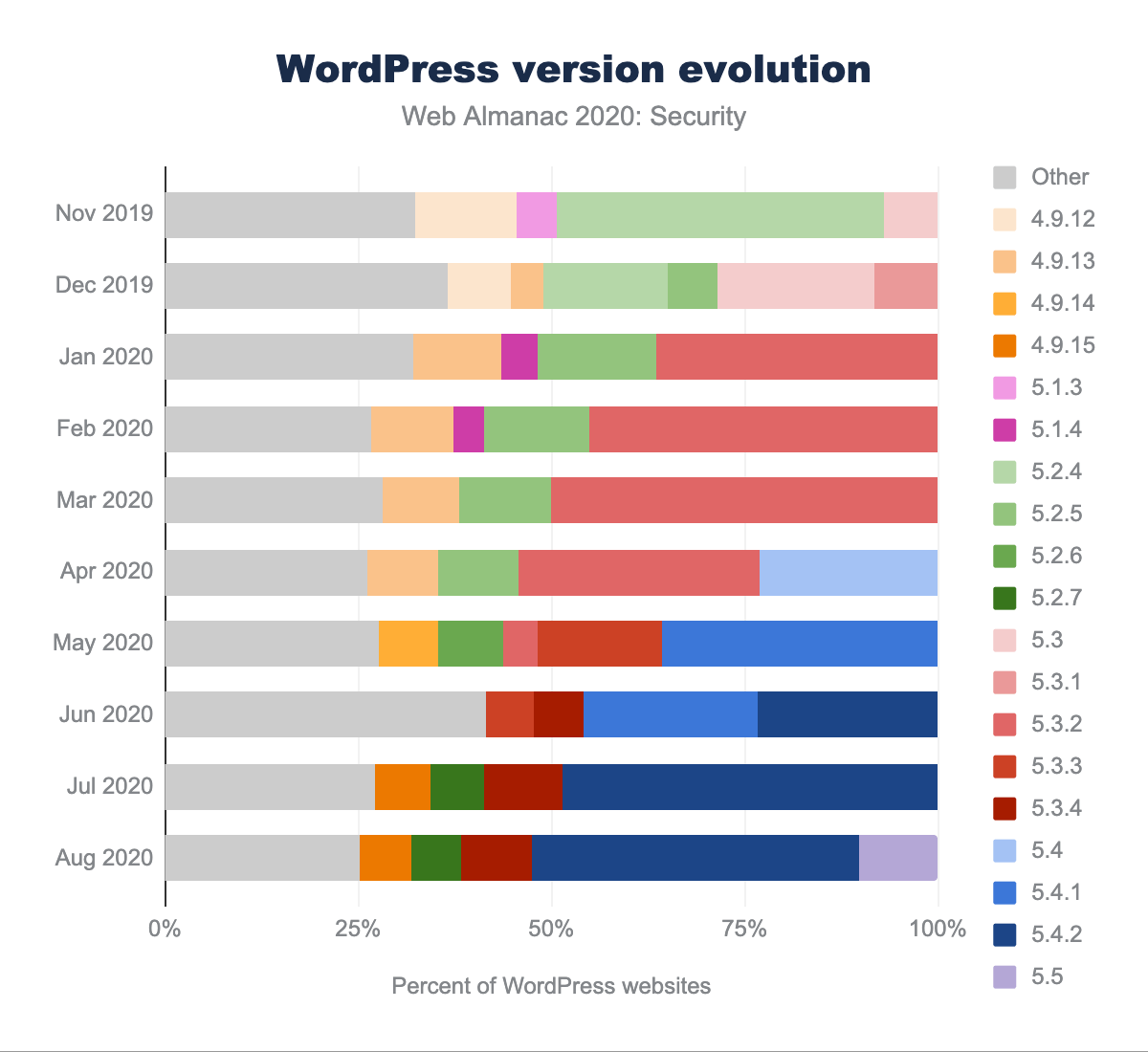

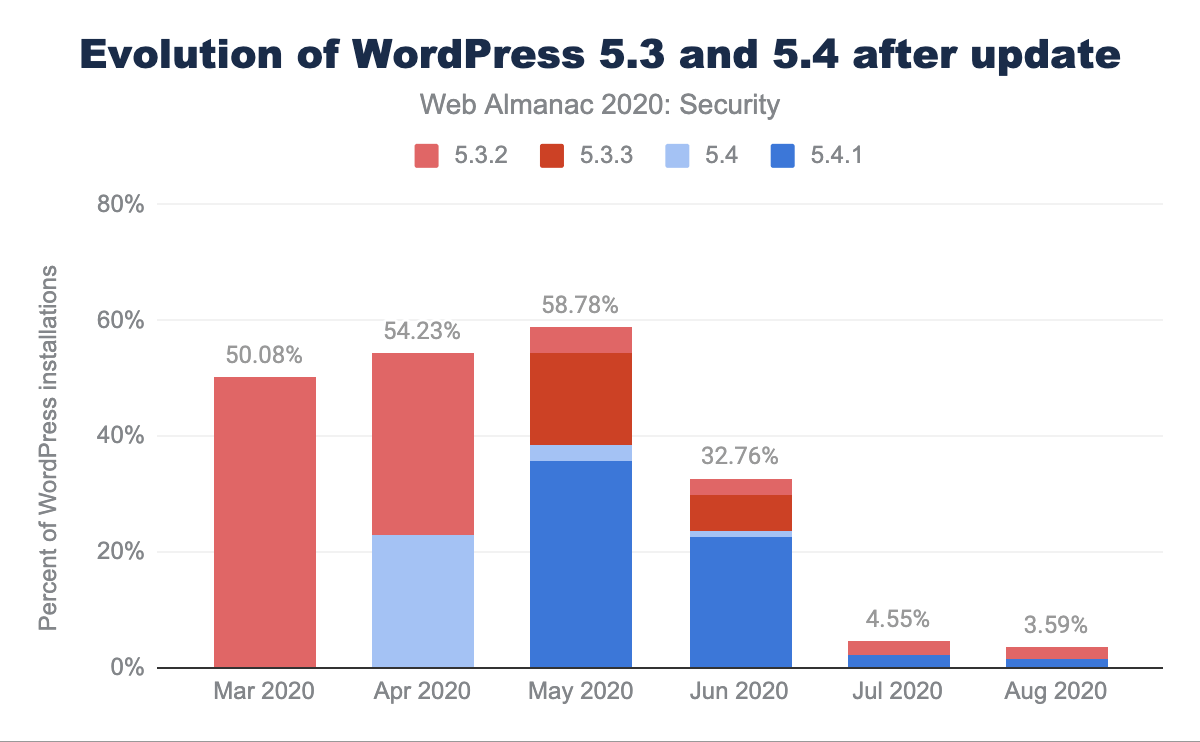

As one of the most popular Content Management Systems, WordPress is an attractive target for attackers. As such, it is important for website administrators to keep their installation up-to-date. By default, updates are performed automatically for WordPress, although it is possible to disable this feature. The evolution of the deployed WordPress versions are displayed in the above figure, showing the latest major versions that are still actively maintained (5.5: purple, 5.4: blue, 5.3: red, 5.2: green, 4.9: orange). Versions that have a prevalence of less than 4% are grouped together under “Other”. A first interesting observation that can be made is that as of August 2020, 74.89% of the WordPress installations on mobile home pages are running the latest version within their branch. It can also be seen that website owners are gradually upgrading to the new major versions. For instance, WordPress version 5.5, which was released on August 11th 2020, already comprised 10.22% of the WordPress installations that were observed in the crawl for August.

Another interesting aspect that can be inferred from the graph is that within a month, the majority of WordPress sites that were previously up-to-date, will have updated to the new version. This appears especially true for WordPress installations on the latest branch. On April 29, 2020, 2 days before the start of the crawl, WordPress released updates for all their branches: 5.4 → 5.4.1, 5.3.2 → 5.3.3, etc. Based on the data, we can see that the share of WordPress installations that were running version 5.4, reduced from 23.08% in the April 2020 crawl, to 2.66% in May 2020, further down to 1.12% in June 2020, and dropping below 1% after that. The new 5.4.1 version was running on 35.70% of the WordPress installations as of May 2020, the result of many website operators (automatically) updating their WordPress install (from 5.4 and other branches). Although the majority of website operators update their WordPress either automatically, or very quickly after a new version is released, there still is a small fraction of sites that keep stuck with an older version: as of August 2020, 3.59% of all WordPress installations were running an outdated 5.3 or 5.4 version.

jQuery

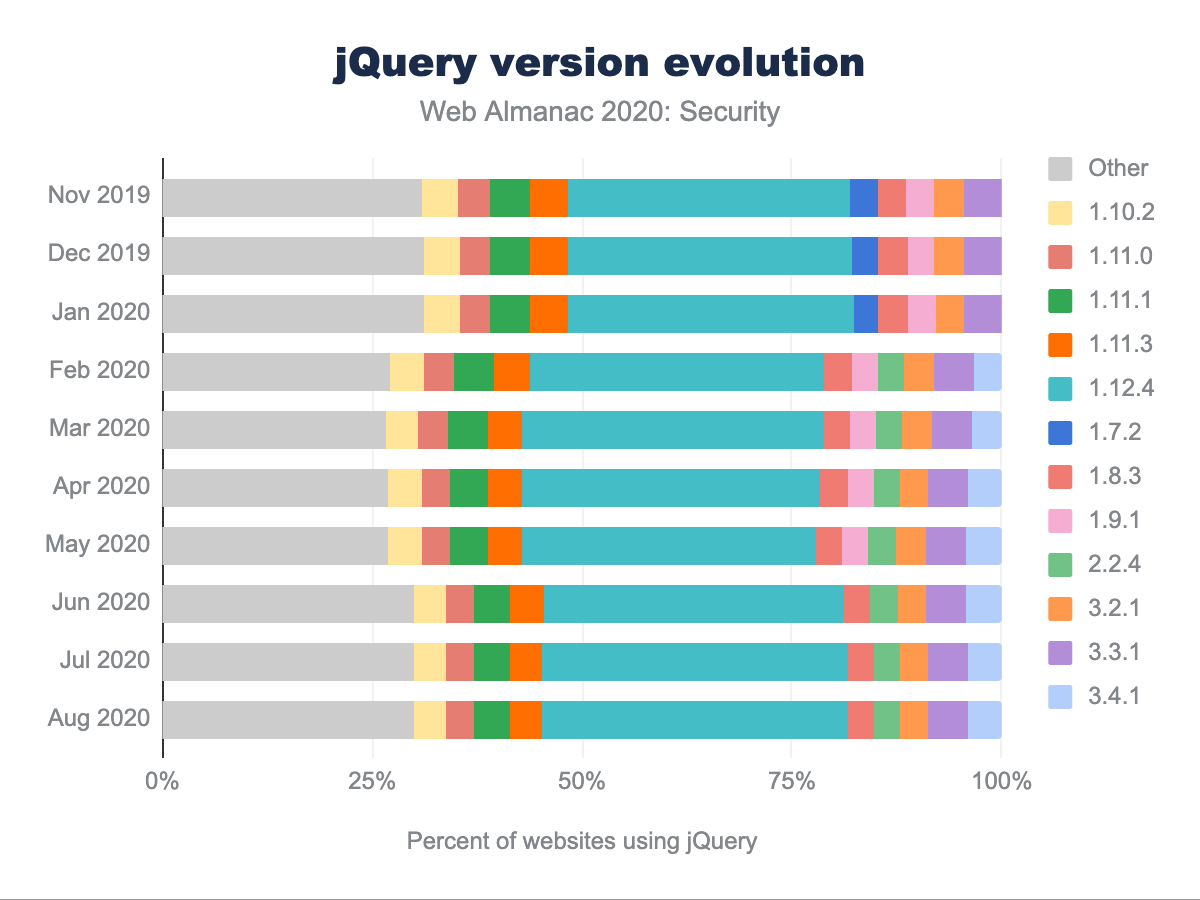

One of the most widely used JavaScript libraries is jQuery, which has three major versions: 1.x, 2.x and 3.x. As is clear from the evolution of jQuery versions that are used on mobile home pages, the overall distribution is very static over time. Surprisingly, a significant fraction of websites (18.21% as of August 2020) are still running an old 1.x version of jQuery. This fraction is consistently decreasing (from 33.39% in November 2019), in favor of version 1.12.4, which was released in May 2016 and unfortunately has various medium-level security issues.

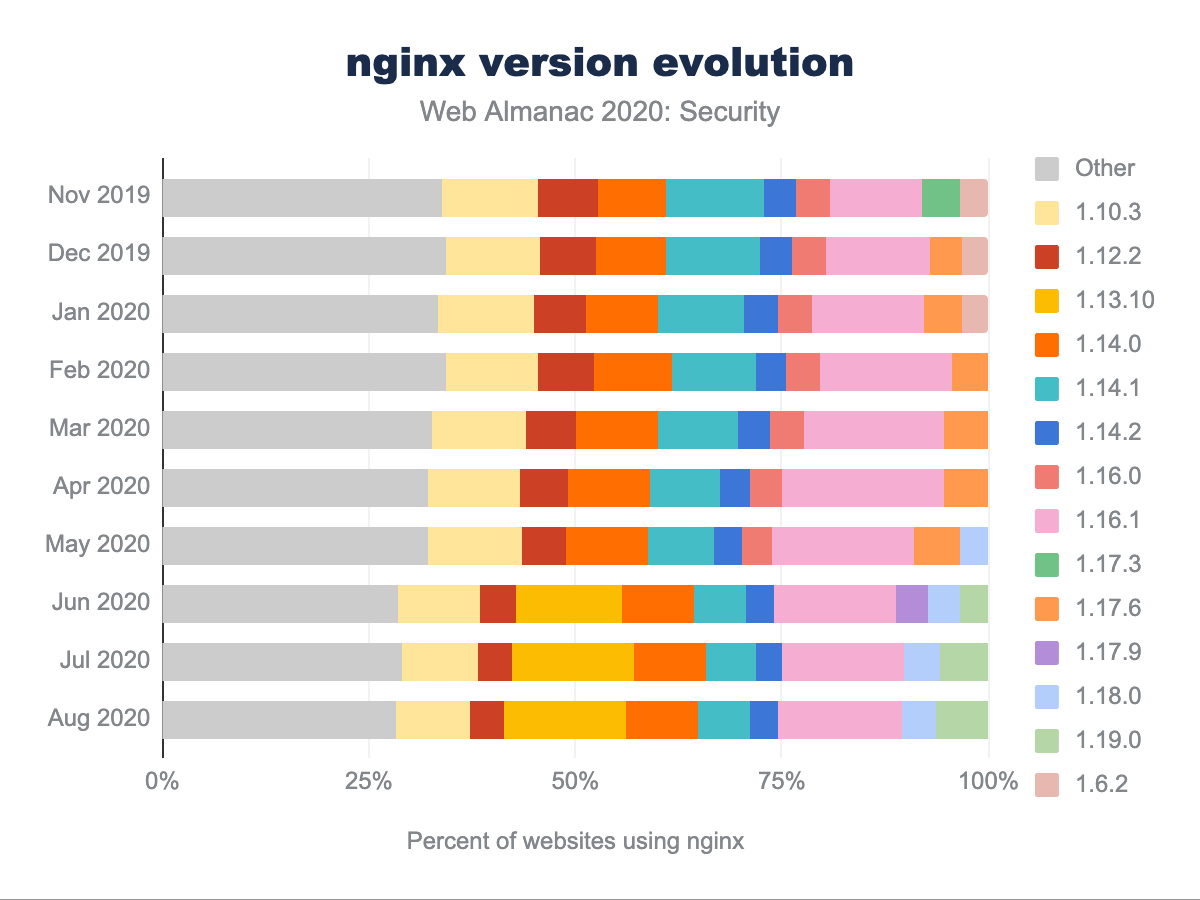

nginx

For nginx, one of the most widely used web servers, we see a very static and diverse landscape in terms of the adoption of different versions over time. The largest share that any nginx (minor) version had among all nginx servers over time was approximately 20%. Furthermore, we can see that the distribution of versions remains fairly static over time: it is relatively unlikely that web servers are updated. Presumably, this is related to the fact that no “major” security vulnerability has been found in nginx since 2014 (affecting versions up to 1.5.11). The last 3 vulnerabilities with a medium-ranked impact (CVE-2019-9511, CVE-2019-9513, CVE-2019-9516) date from March 2019 and can cause excessively high CPU usage in HTTP/2-enabled nginx servers up to version 1.17.2. According to the reported version numbers, more than half of the servers could be susceptible to this vulnerability (if they have HTTP/2 enabled). As the web server software is not frequently updated, this number is likely to stay fairly high in the coming months.

Malpractices on the web

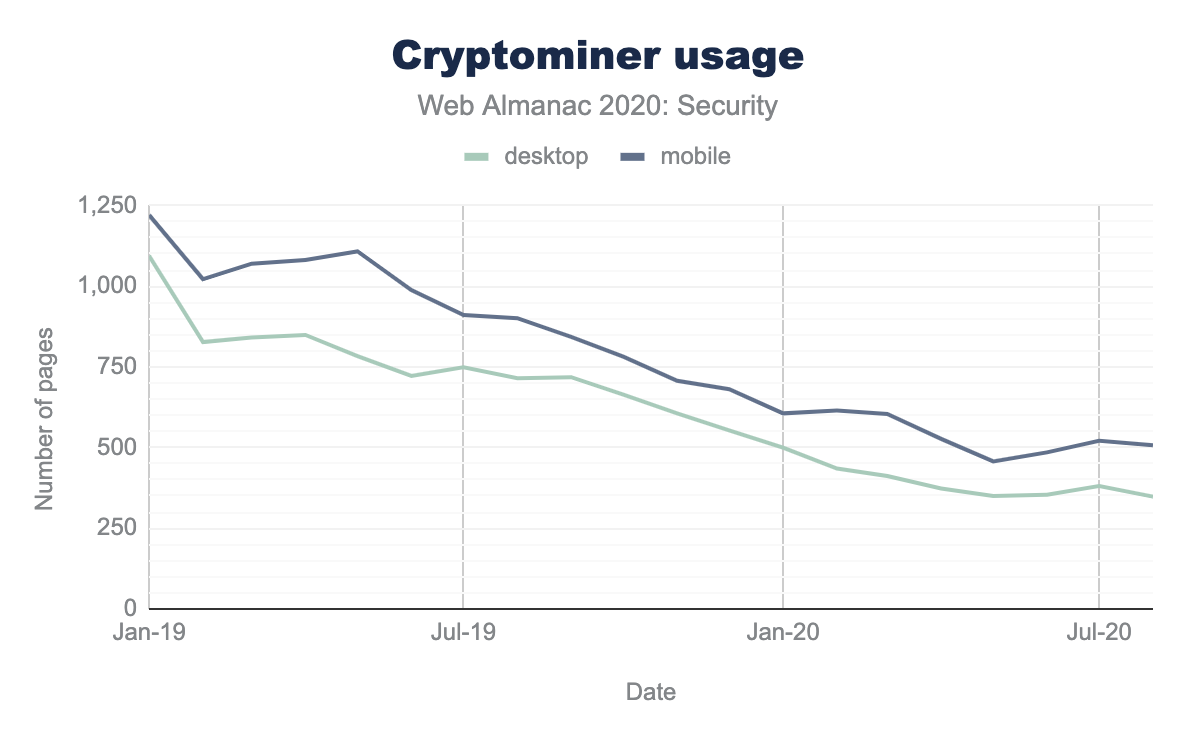

Nowadays, the performance of the used technologies plays a particularly relevant role. To this end, technologies are constantly being further developed, optimized, and new technologies launched. One of these new technologies is WebAssembly, which has become a W3C recommendation as of the end of 2019. WebAssembly can be used to develop powerful web applications and has made it possible to run almost native high-performance computing in web browsers. No rose without a thorn however as attackers have taken advantage of this technology, and this is how the new attack vector cryptojacking came into existence. Attackers used this technology to mine cryptocurrencies on the web browser by using the power of visitor’s computers (malicious cryptomining). This is a very attractive technique for attackers – inject a few lines of JavaScript code in the web page and let all visitors mine for you. Because some websites may also offer bona fide cryptomining on the web, we can’t generalize that all websites with cryptomining are in fact cryptojacking. But in most cases, website operators don’t offer an opt-in alternative for visitors, and the visitors remain still uninformed as to whether their resources are being used while browsing the website.

The figure above shows the number of websites utilizing cryptomining in the last two years. We see that from the beginning of 2019, interest in cryptomining is getting lower. In our last measurement, we had a total of 348 websites including cryptomining scripts.

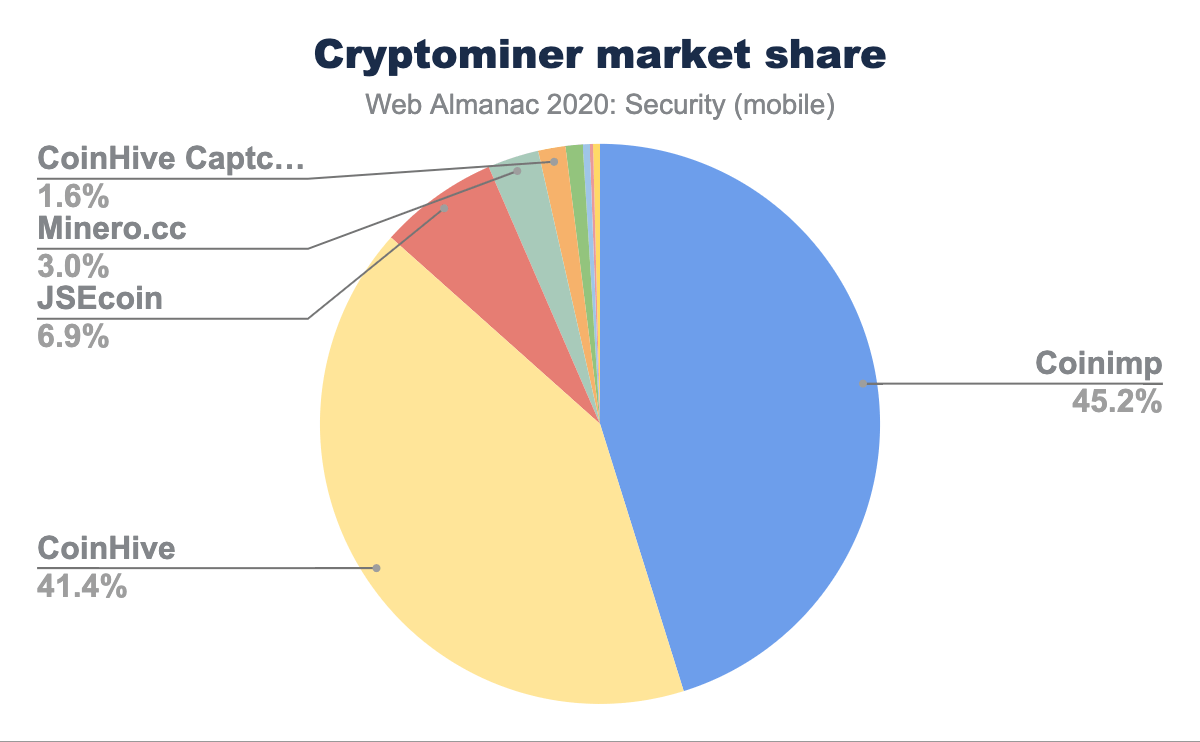

In the next figure, we show the market share of cryptominer on the web based on August’s dataset. Coinimp is the most popular provider with a 45.2% market share. We found that all of the most popular cryptominers are based on WebAssembly. Note that there are also JavaScript libraries to mine on the web, but they are not as powerful as solutions based on WebAssembly. Our other result shows that half of the websites including a cryptominer utilize a cryptomining component of discontinued service providers (such as CoinHive and JSEcoin), which means that although the cryptomining scripts are included on those web pages, they are no longer active and thus no cryptomining will occur in practice.

Conclusion

One of the most prominent developments in terms of web security over the last year has been the increased adoption of security headers on (the long tail of) the Web. Not only does this mean that overall users are generally better protected, more importantly, it shows that the security incentive of website administrators has generally increased. This increase in usage can be seen for all the different security headers, even for the ones that are non-trivial to implement, such as CSP. Another interesting observation that can be made, is that we saw that websites that adopt one security header, are also more likely to adopt other security mechanisms. This shows that web security is not just considered as an afterthought, but rather a holistic approach where developers aim to defend against all possible threats.

On a global scale, there is still a long way to go. For instance, less than a third of all sites have adequate protection for clickjacking attacks, and many sites are opting out of the protection (enabled by default in certain browsers) against various cross-site attacks, by setting the SameSite attribute on cookies to None. Nevertheless, we have also seen more positive evolutions: various software on the technology stack are enabling security features by default. Developers that build a website using this software will start off with an already-secure environment and would have to forcefully disable protections if they so desire. This is very different from what we see in legacy applications, where enhancing security might be more difficult as it could break functionality.

Looking ahead, one prediction that we know will come true is that the security landscape will not come to a standstill. New attack techniques will surface, possibly prompting the need for additional security mechanisms to defend against them. As we have seen with other security features that have only recently been adopted, this will take some time, but gradually and step by step we are converging to a more secure web.