Page Weight

Introduction

Unless you’re a web performance junkie like me, the weight of a web page is about as exciting as licking stamps. But, I’m going to try my best to convince you as to why page weight is not only important but arguably the most important factor affecting creators, hosting providers, and consumers. To that end, we’ll use real data to show how the weight of a page influences the performance of the website or web application, how page weight can impact user experience, and some ways we can reduce the weight of our web pages.

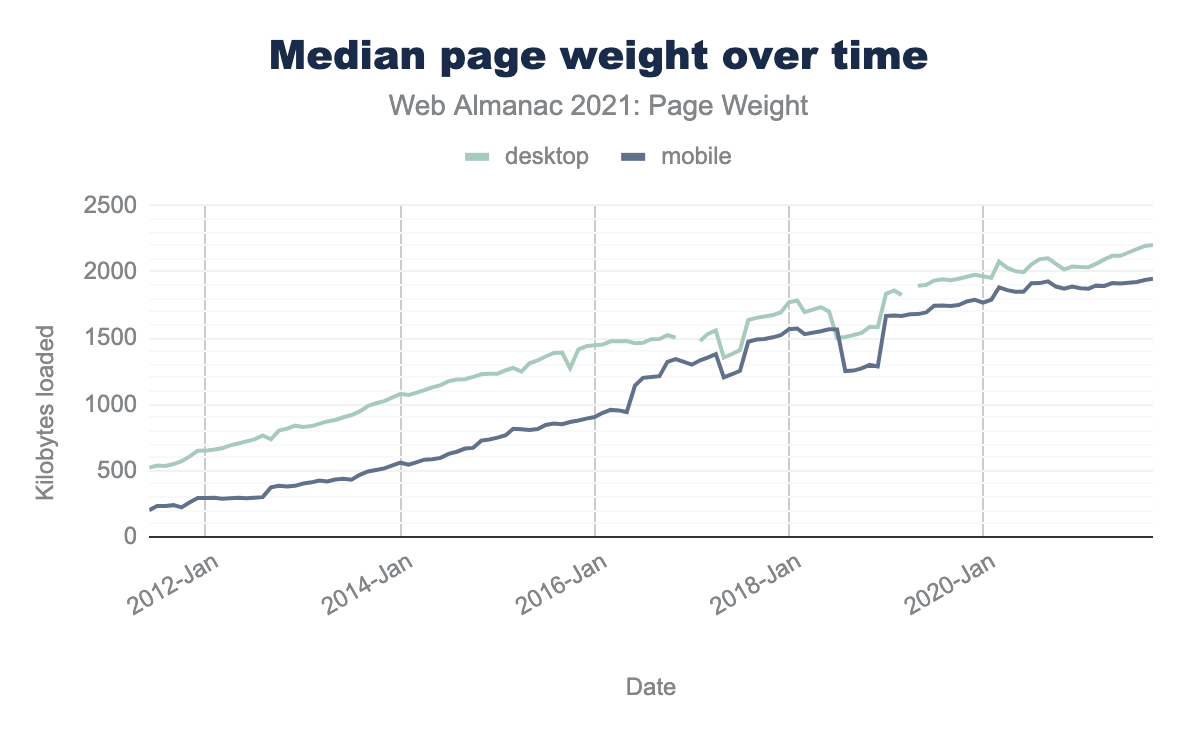

In the past decade, average web page weight has grown a whopping 356 percent, from an average of about 484 kilobytes to 2,205 kilobytes. That increase can be explained as a function of supply and demand. Faster computer processors, data transmission, and how data is stored and made available have all advanced to keep up with increased use of images, video, audio, fonts, data collection and processing, and connected services like analytics, monitoring, and alerting functionality for web sites and web applications.

All seems well, if you’re fortunate enough to own a high end smartphone, desktop or laptop computer costing thousands of dollars, and you’re connected to an expensive high speed internet provider or 5G data plan. But the pleasure of belonging to that class of internet user starts to break down when you’re relegated to using a slow 3G or 4G data plan with unpredictable internet connectivity. For a large segment of internet users, waiting for a page that may never fully load breaks the promise of the internet even to the point of putting lives at risk during emergencies.

A lot of energy is used to power data centers and the devices they serve. We can help reduce overall energy demands by keeping our file payloads smaller which also keeps payload transmission faster and more efficient.

Google now penalizes a website’s search ranking for those that fail to achieve good Core Web Vitals. One of their metrics for assessing success or failure is page weight. If you are interested, you can test your site using Google PageSpeed Insights and Google Measure. Both provide valuable insights into how to solve performance and user experience problems caused by heavy web pages.

To understand and find opportunities to keep web pages lighter and faster, it’s instructive to examine what page weight actually is. So let’s delve deeper.

What is page weight?

Page weight describes the total number of bytes of a particular web page. A web page is comprised of specific elements and assets that can be rendered and viewed in a web browser, including:

- The HTML that makes up the page itself.

- Images and other media (video, audio, etc) embedded into the page.

- Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) used for styling the page.

- JavaScript to provide interactivity

- Third-Party resource containing one or more of the above.

Each of those resources exact a cost in weight (byte size), and computational resources to transmit, process and render in a web browser. While they have similar cost in some regards (storage and transmission), the CPU cost of some resource types may be more costly in those regards than others.

The process of managing web page resources for use when requested have rapidly changed over the past decades. Part of those changes were predicated on making web page resources more efficient and more quickly transmittable when requested. Let’s examine three impacts of page weight for resources:

Storage

Page resources need to be stored ready for retrieval when requested. Image, video, CSS, JavaScript, and font files assets are stored in multiple places: on servers, on local devices, and in memory. Each file, ranging from a few bytes to many megabytes in size, therefore has a cost impact in multiple places. While server storage costs may seem relatively cheap, limited storage on devices can result in assets being evicted from caches or memory resulting in more downloads and more costs.

Many people don’t understand, or pay little attention to, the negative impact those types of unoptimized assets have on page loading performance. When reviewing today’s websites, I routinely discover images that exceed four megabytes in size, and embedded video files that are many times that value.

Fortunately, there are also options and optimizations that can be applied that can significantly lower the size of files stored at rest from compression, to using the appropriate file format for media to offloading content to a dedicated CDN who can handle this for your to lighten the weight of a web page, often at little to no cost.

Transmission

When a user requests a web page via HTTP, all files needed by the page are then requested. Files are located and sent back to the requesting device and, if all goes well, the requester’s browser will take the payload, and process and render it as part of the larger web page on the requesting user’s screen. Page weight becomes important during the transmission process because the size of the file determines how long it will take to complete the transfer of the resources, which will then ultimately impact the rendering of the results.

A negative effect of large page weight is due to latency and bandwidth constraints. Latency measures the time it takes for the request to connect to the server storing the files and begin the process of transporting those files, while bandwidth measures the time it takes to download the resources. If a bunch of files are requested, no matter the technology, there is a limit on how much can be processed and transferred in any given period. I’ve audited WordPress sites that request as many as 170 files or more, which ensures terrible page loading performance starting with high latency periods.

Many optimizations can improve transfer/loading time, such as compressing and combining certain file requests, using HTTP/2—or the newer HTTP/3—protocols, and using a modern browser’s ability to preconnect to and preload certain files to speed the whole process up, but ultimately page weight will still have an impact here. The Performance chapter covers a wide range of factors that effect page loading performance.

Rendering

A web browser is ultimately software that makes requests to for resources on behalf of users (hence the term user agent). The results of those requests are handed off to the browser’s rendering engine to process and then recreate the web page you asked for. It’s not hard to deduce that the larger the total amount of page weight, the more the browser engine must process and render to the browser screen, and so the longer it’s going to take.

If too many files, especially large media and large complex scripts must get retrieved, read, processed, and then finally rendered by the browser before the content becomes available, then this increase the chance that pages will take so long to load that users will abandon them.

Large payloads can also overwhelm the amount of client-side resources available on the users smartphone or computer causing it to stall and even crash the device. Users who have the good fortune to subscribe to high speed cable internet services, or 5G data plans for high end devices will seldom experience these problems. But again, a large percentage of internet users don’t have access to those levels of internet services and devices.

Assets

As explained in last years chapter, we have not really changed what types of assets are used on web pages over the years, but there are some notable exceptions.

Images

Static files reside by themselves and are used as resources to help build out and render web pages. Images, video, audio, and font files are all examples of static assets. Images make a large percentage of the average web page’s weight so, let’s use images for our example.

Image formats like PNG and JPEG are widely supported by all browsers. More recent image formats, such as WebP and AVIF offer higher quality with smaller file sizes have gained popularity. WebP is supported by most modern browsers, while AVIF is newer and less supported. With the <picture> tag, you can use modern image formats while providing JPEG and PNG fallbacks. Make sure your images are optimized for the web-the Media chapter covers this in much more detail. Failing to properly size and compress images for your site will exact a high price on performance.

A word about the proliferation in the use of JavaScript

JavaScript can be a wonderful tool to use for creating a dynamic website, but using it unchecked can create serious performance problems and a horrible experience for the user. There’s been a proliferation in the use of complex JavaScript web frameworks and libraries over the past decades and the sheer amount of JavaScript is a large percentage of total page weight. Some JavaScript can cause sizes for a site to skyrocket leading to serious performance bottlenecks. Some are so bad that a site can become unstable or even unusable. Blocking scripts, that must be transmitted, processed, and executed before the page can finish rendering enough page assets for users to interact with it. That can cause confusion, frustration, and abandonment by the user.

Nine times out of ten when a site stalls, it is a blocking JavaScript that is causing your smartphone to run out of processing resources or memory is to blame. The judicious, expert use of JavaScript can create great user experiences. But remember this: JavaScript is executed on the client side. It’s using the client computers resources to process and execute the script, and there is a finite amount of resources on every device. Once again, not everyone is glued to the newest Google Pixel or Apple smartphone. The JavaScript chapter contains a wealth of information about this issue.

Third-party services

Page weight can also be affected by external services called by web page. Some of those services include CDN’s, analytics, chat bots, forms, and other data collection and processing methods. I find this to be one of the fastest growing problem areas that result in bloated page weight. Many of these third-party services use outdated, poorly-written JavaScript and querying techniques that take much longer to execute than they should, and the site owner has little control over how that third party impacts the loading of a page. Suffice it to say that inquiring about how a service will affect your page loading performance is very important. So is testing their impact.

Caching

Caches, are allow resources to be served quickly, thus avoiding the cost of the download again. Caches exist on both users’ browser, but also on servers. Caching of optimized assets dramatically lowers page weight and page loading time because the asset is immediately available, removing the need to execute and entire request process. While not reducing the overall page weight, they can help reduce the impact.

Page weight by the numbers

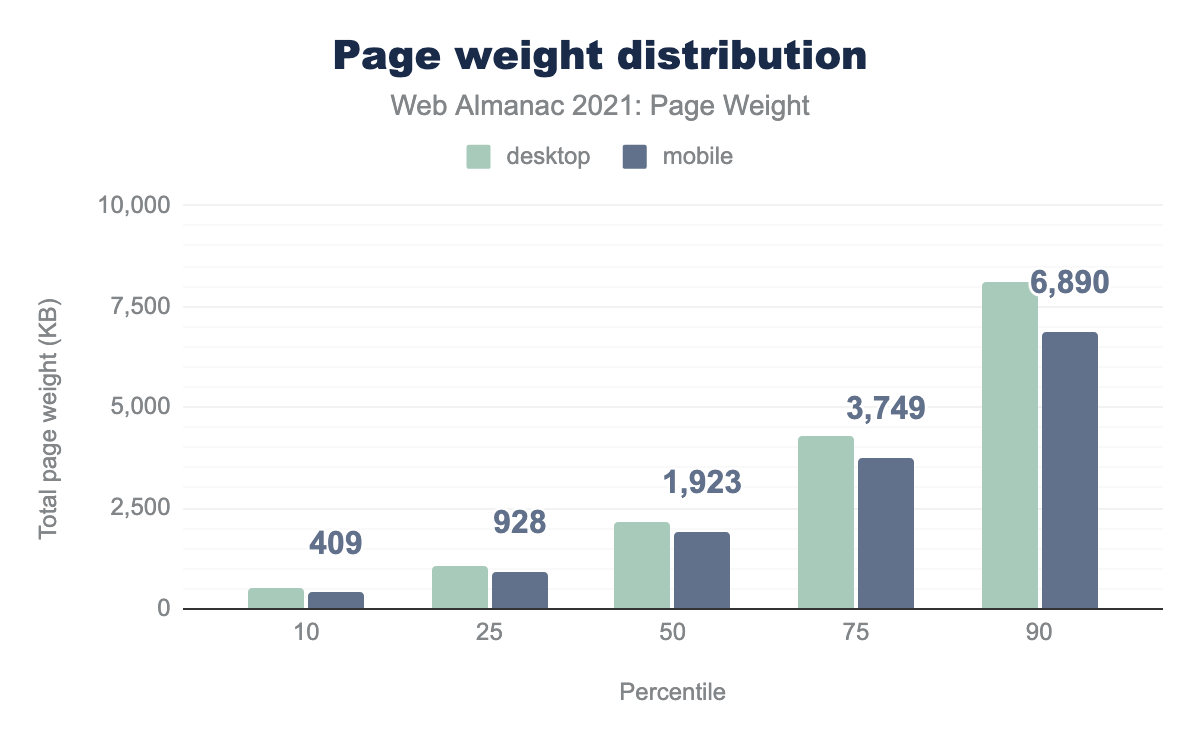

Looking at the page weight on both desktop and mobile devices, the difference is generally small between them despite the often-different capabilities of these devices:

We are closing in on 6.9 MB of page weight on mobile and 8.1 MB on desktop at the 90th percentile.

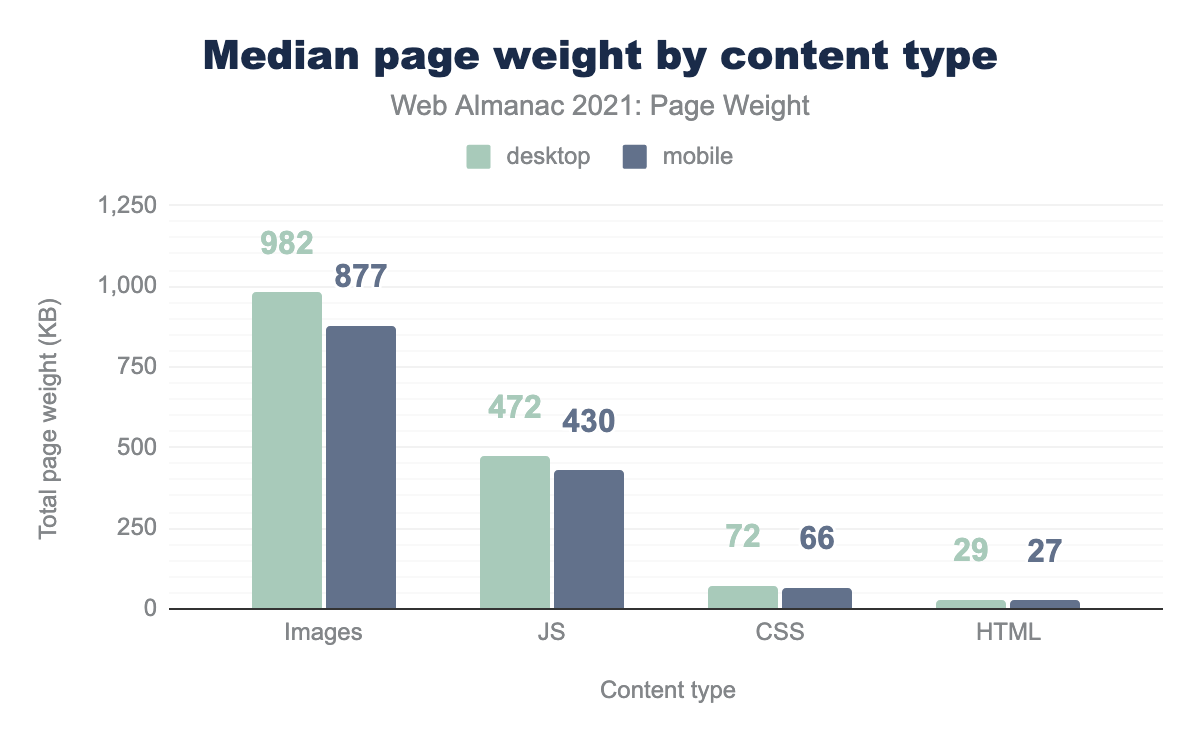

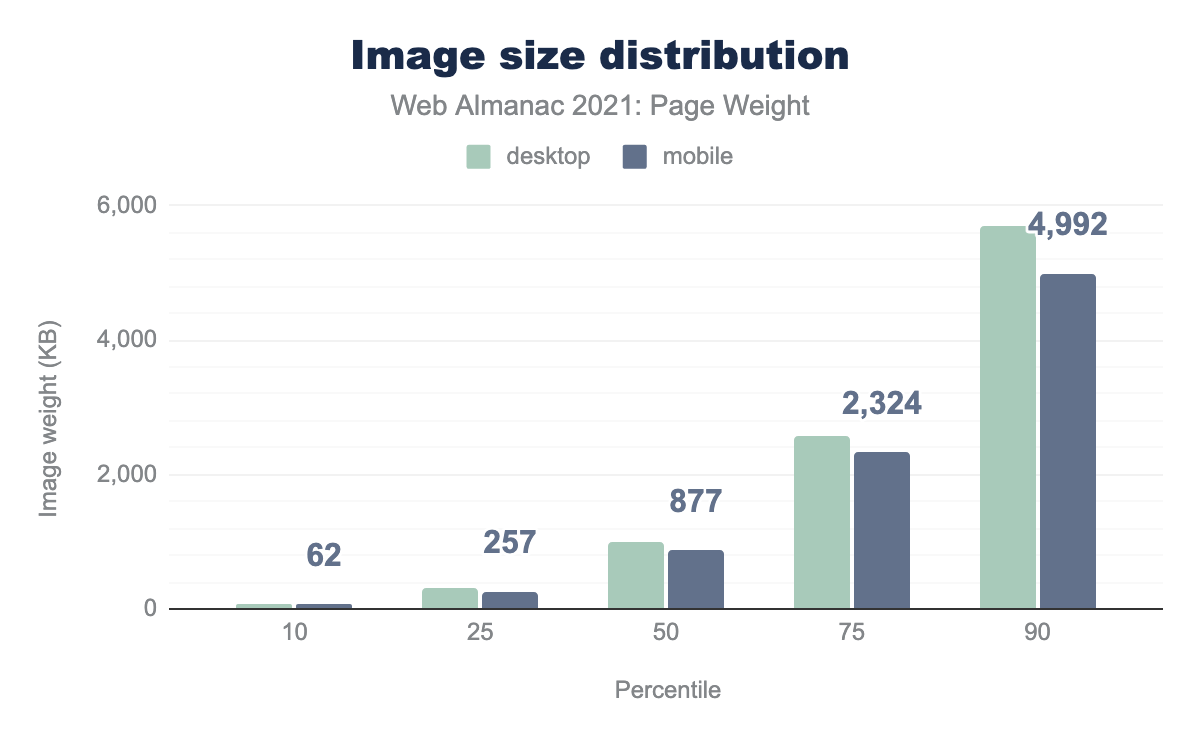

A closer inspection at the median, shows that the images remain the largest resource followed by JavaScript.

Let’s look at the growth over time:

The trend of page weight growth couldn’t be clearer. We’re on an upward trajectory that shows no sign of abating.

Requests

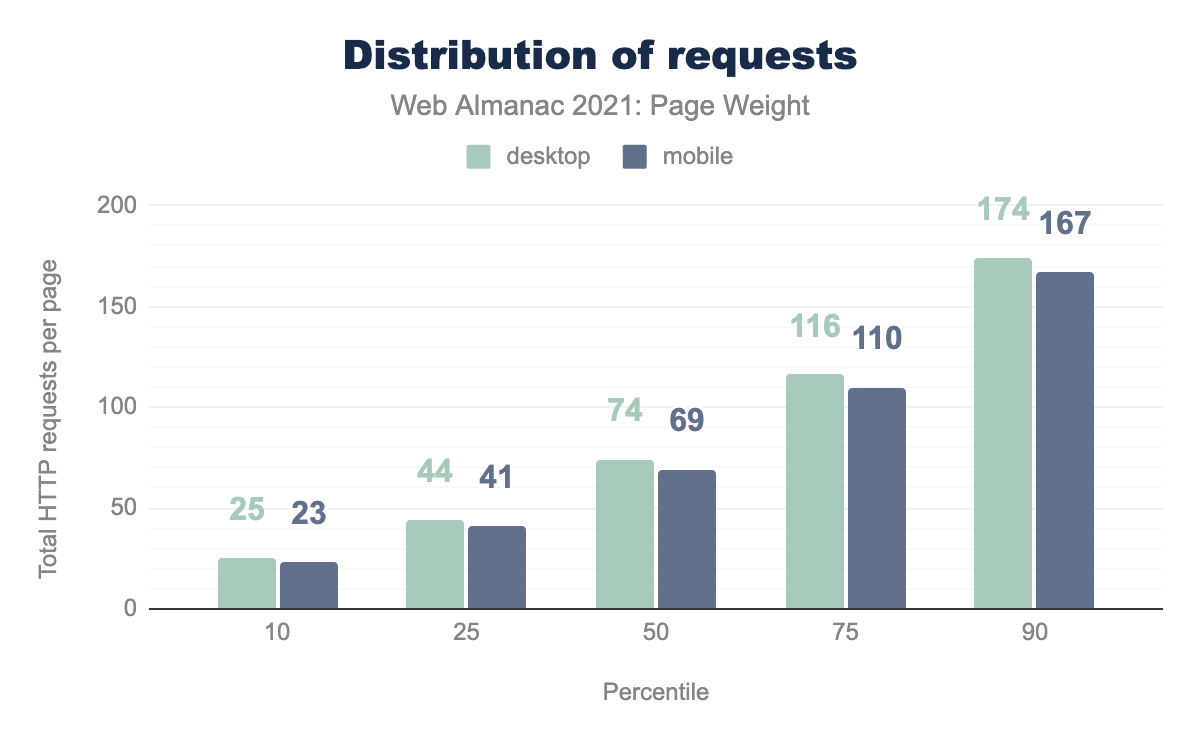

As previously explained in this chapter, as well as the size of resource, the number of requests can have negative impact on page loading performance and so are another measure of page weight.

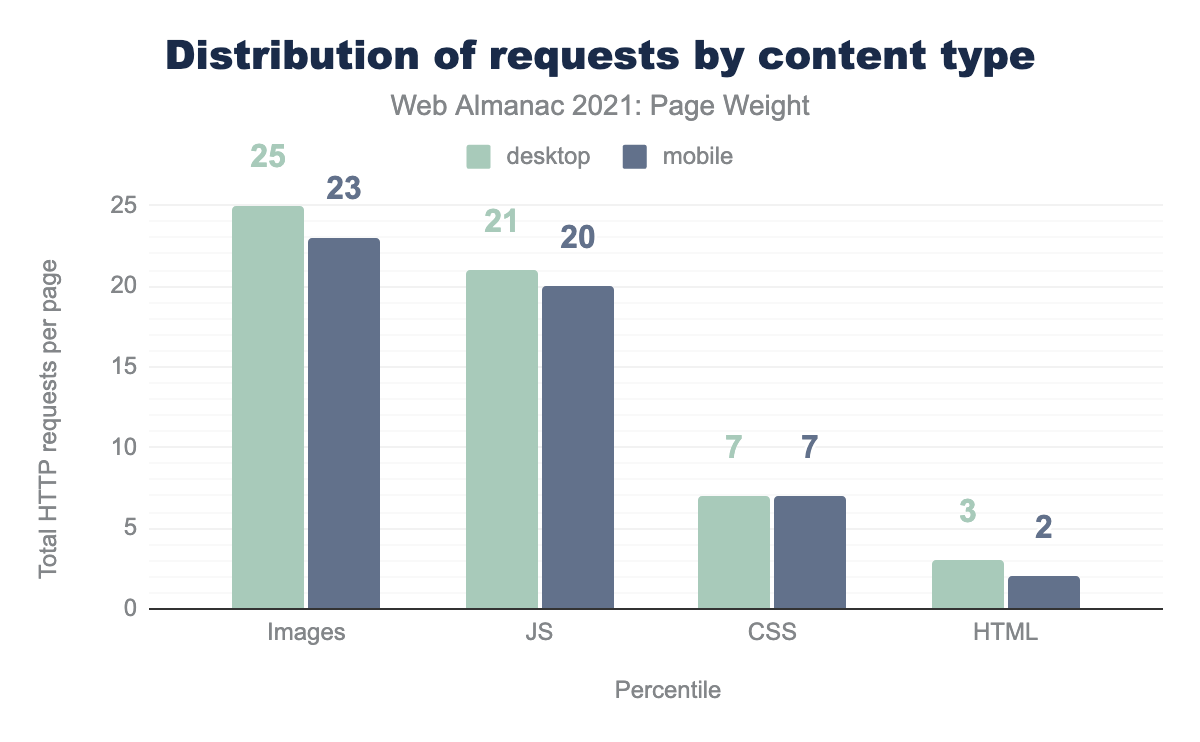

The request distribution shows that the difference between desktop and mobile is not significant, with desktop leading the way.

The difference between current results for this year and last actually shows a tiny decrease in the average number of GET requests across most of the percentiles. Let’s hope that trend continues downward.

Something else worth noting: the median request on desktop at this time is the same as last year (74), yet the page weight has ticked up (141 kb).

Images again make up the largest number of requests, though JavaScript is closing in as the gap has narrowed slightly in the last year. Images shows a reduction of 4 requests between the two years—perhaps a result of more lazy-loading since this was made available natively via simple HTML attributes?

File formats

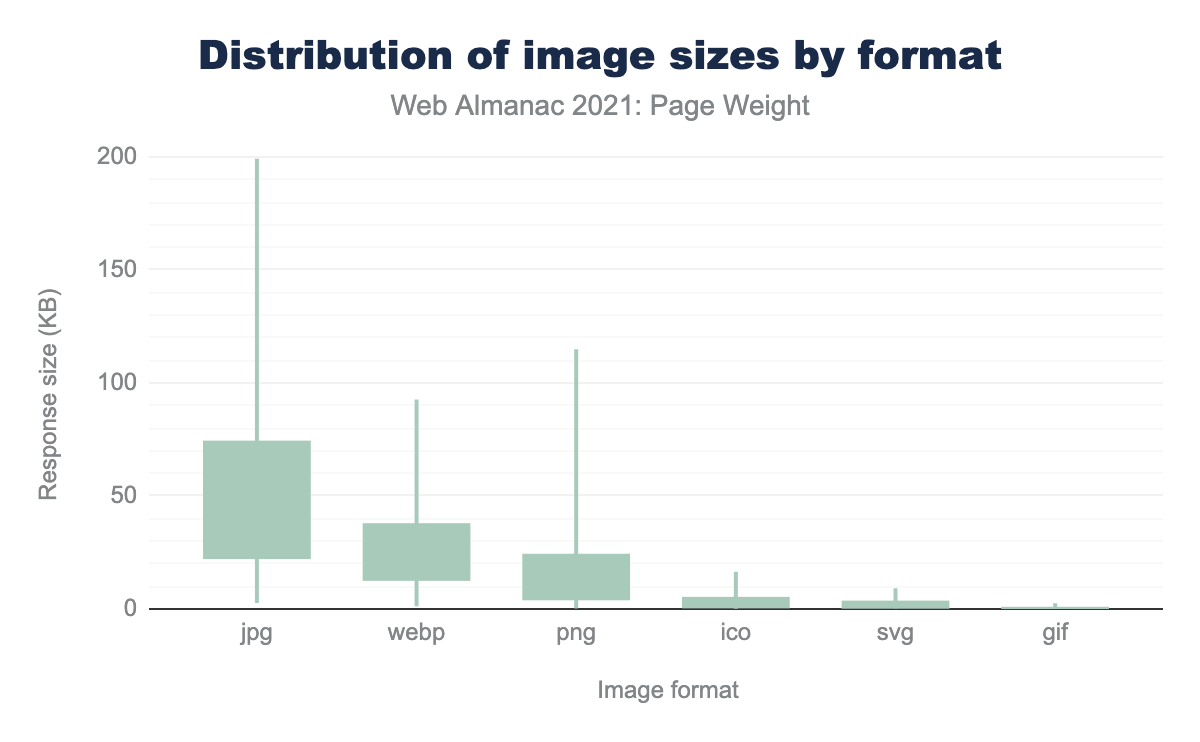

We know images are responsible for a large percentage of web page weight. The above graphic shows the top sources of image weight and the weight distribution. Top 3: JPG, WebP and PNG. Compared to last year, we see an increase in WebP usage now it is finally supported in all major browsers. PNG remains popular for use cases such as icons and logos.

Image bytes

Looking at total image bytes shows us that this metric has remained virtually unchanged from the previous year. One reason for this could be an increase in the number images being served by content distribution networks (CDN), which apply strong optimizations to images as they are uploaded to their servers thus keeping any growth in check for new images.

Conclusion

How important is it to keep web pages light? Overall page weight affects page loading speed, and page loading speed affects user experience. Google’s Web Vitals program focuses on user experience, especially for mobile users, with a direct impact on Google Search rankings. So, there is a real incentive and a real consequence to keep web pages as light as possible.

But will impact on search rankings translate into direct pressure to lighten page loads? What about web titans, like Amazon? Is there incentive for hugely popular web sites to worry about page weight? Perhaps. The Amazon’s may want to take advantage of reducing the size of page assets and services to reduce the spend required to serve those pages, or maybe they want to move into newly emerging markets where users may not be able to buy super-fast smartphones or have access to 5G data networks or high-speed cable providers. Time will tell.